Bestselling author Laura McKowen published a personal essay in The New York Times recently about her struggles with quitting Instagram. It’s a refreshing read, written from the perspective of someone who A) intimately understands what addiction feels like — McKowen stopped drinking alcohol seven years ago and currently helms an online sobriety platform — and B) recognizes that social media is a dangerous addiction in its own right.

McKowen describes building her entire life around Instagram. She accrued 80,000 followers, which helped her network, secure a book deal and promote projects. The app also began to take over her sense of self. McKowen would spend up to six hours a day refreshing feeds, looking for self-confidence boosts in the comments section. Too often, though, she’d hit the pillow anxious and exhausted — derailed by the opinions of accounts she didn’t even know, or preoccupied by the posts competitors in her space.

Eventually, noticing the damaging effect her Instagram use was having on her relationship with her daughter and boyfriend, she quit. She told the world she was quitting, in an essay, knowing from experience how crucial public accountability is. But months later, feeling light and loose on a family vacation to visit her mother in Hawaii, she relapsed. McKowen reactivated her account and posted a photo from the beach, announcing her intention to use Instagram again, only this time to “share joy.”

What followed was a long evening of miserably obsessing over likes, comments … and unfollows. Some of her Instagram followers, surprised to see her back, roundly admonished her for not sticking to her word and staying off the platform. If that dramatic irony sounds too absurd to process, imagine how McKowen felt. She couldn’t sleep, the wayward decision suddenly dominated her family’s trip, and in the morning, she knew she had to deactivate her account for good.

She concluded: “The buzz of fear in my stomach, the clutch of anxiety around my throat, the endless procession of negative thoughts, the fractured texture of my attention … it’s simply not worth it.”

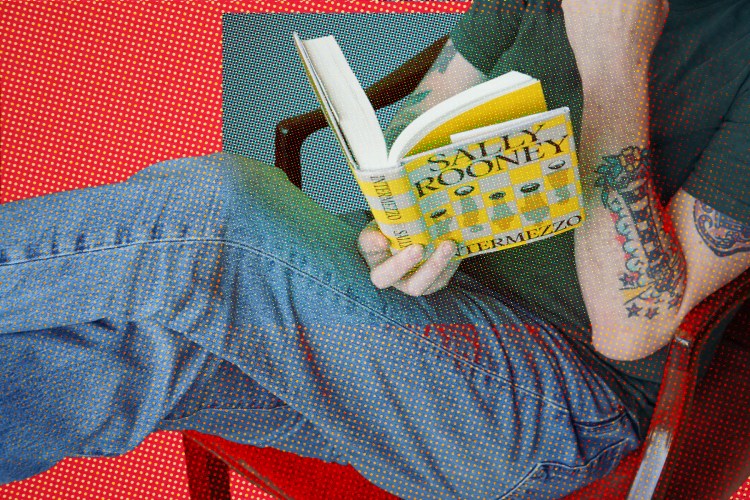

This sort of story is incredibly important at this moment, when Facebook is seriously considering building an “Instagram for Kids,” and millions of young people can’t even conceive of a social life that doesn’t revolve around Instagram. According to a study published earlier this year, Gen Z spends nearly an hour a day on Instagram. Traditionally, a stat like that is bandied out by *older folks* as proof of all that’s wrong with young people. You know: “How lazy! Go outside! Read a book!”

But it’s high time we start acknowledging the truth — kids didn’t ask for Instagram. None of us did. It was delivered to us by a group of Silicon Valley app developers who are fluent in what’s known as “behavioral design.” Back in 2014, a Stanford University lecturer explained to Business Insider, somewhat ominously, that Instagram founder Kevin Systrom “knows a lot.” Systrom himself went to Stanford, and majored in symbolic systems, “a field that lies at the intersection of psychology and computer science.”

At its very core, Instagram is designed to be addictive. Earlier this year, ex-employees of Apple, Facebook and Google dished on the three-pronged approach that developers shoot for when programming the apps we can’t get enough of: sufficient motivation, an action, and a trigger. In Instagram-speak, this could be summed up as a user’s desire for something to happen (they’ve come to associate Instagram with the release of happy neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin), a user’s ability to interact with it without any issue (open the app with a click of the button and like something right away) and a user’s incidental relationship to the app (in the form of vibrations and notifications).

All told, it has the user essentially always interacting with the app. Because even you aren’t actively liking things, you’re either thinking about scrolling through it again soon, or waiting for it to pull you back in. It’s the first thing you open at the beginning of the day, the last thing you close at the end of the day, a reward after tasks are done, and a mind-dulling activity when you’re feeling down. As app developer Peter Mezyk says: “The success of an app is often measured by the extent to which it introduces a new habit.”

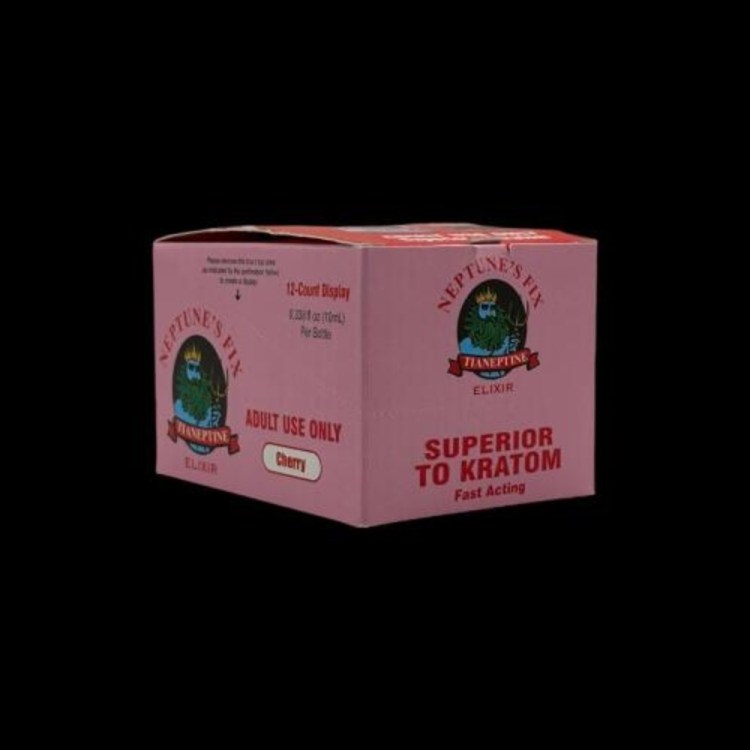

A drug dealer would say the same thing about his most effective supply. No surprise, Instagram has been likened to addictive painkillers by those who investigate the intersection of tech and psychology. So who wins in this scenario? Facebook, of course. The more time you spend using Instagram and Facebook, the more money the behemoth can print in ad revenue.

The kicker, as McKowen surmised in her essay, we now know the right answers. We know that we’re better off with this addictive drug. It subsists on falseness, it trades on our deepest insecurities. It serves no purpose for sustainable self-love. So we do we still use and abuse it? None of us — the youngest of us, especially — can be blamed for getting addicted to this unasked-for nonsense to begin with, but at what point do we have to take our lives back and hit the “Deactivate” button?

Similar to any journey towards sobriety, that’s something only you can decide. You’re already in the habit of using Instagram every day. Perhaps it’s time to start taking stock of how Instagram makes you feel, every day, and from there, make a call on whether it’s something you can continue to tolerate in your life. At the very least, be honest with yourself about the fact that social media is an addiction. It took a while for us to have honest conversations on the topic, and now that we’ve started, we shouldn’t look back.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.