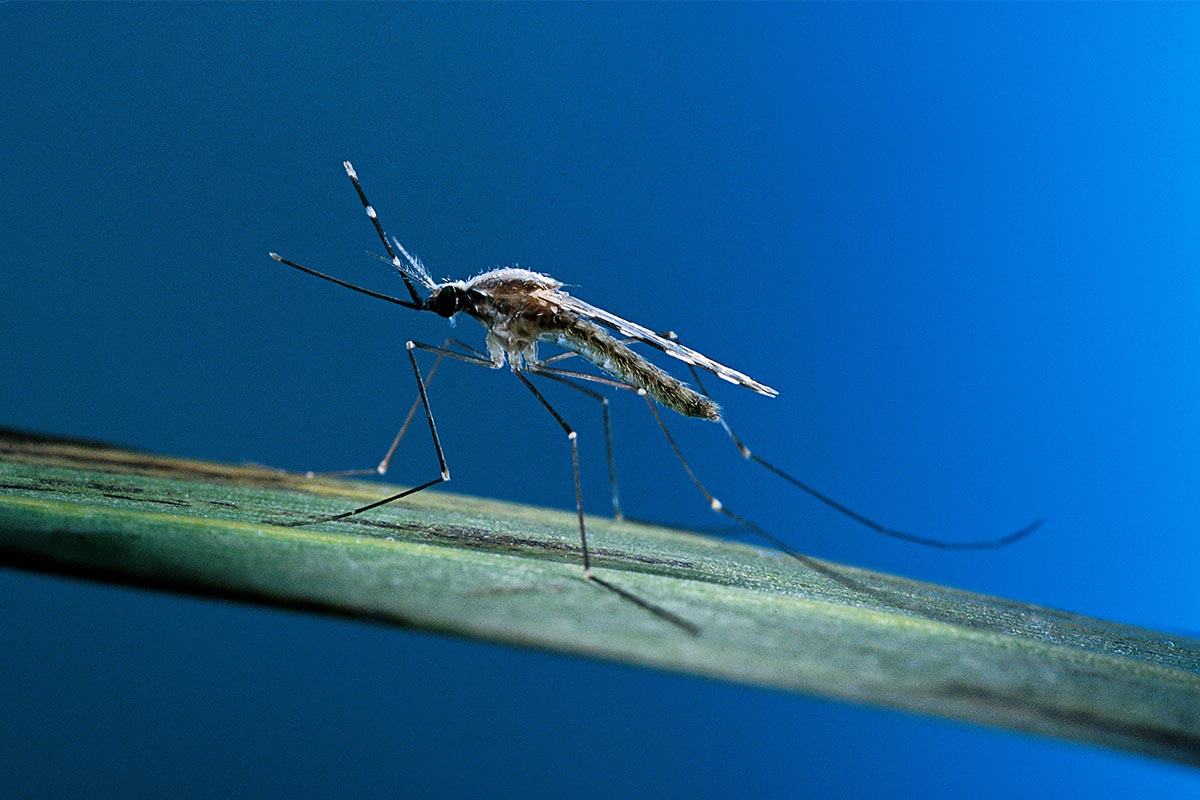

According to a study published last week by a team of Princeton researchers in Current Biology, mosquitoes from areas with dense human populations and dry climates are more likely to feast on humans. The study, entitled “Climate and Urbanization Drive Mosquito Preference for Humans” began three years ago, when the biologists began driving around sub-Saharan Africa and collecting the eggs of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, as The New York Times reported.

Also known as the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti carry a number of disease agents, including Zika, dengue fever and chikungunya. They contribute to the death toll of 725,000 human beings a year from mosquitoes, which has prompted many think tanks to label the fly the “deadliest animal in the world.” But not all Aedes aegypti bother human beings; in fact, half of them prefer the smell of other animals, like rodents. The Princeton team’s mission was to figure out exactly why certain subspecies of the Aedes aegypti spend their days biting human beings.

Their discovery — which has been called “pretty convincing” by Dr. Brian Lazzaro of Cornell, and a “major achievement” by Dr. Niels O. Verhulst of the University of Zurich, two scientists unaffiliated with the program — concludes that mosquitoes from areas with a rainy season followed by a long, hot, dry season are more likely to congregate near (and therefore bite more) human beings. This is related to the way mosquitoes breed. They need water to nest their eggs, and alone among animals, humans have figured out a way to bring a reliable, consistent water source to areas that turn arid for months at a time.

Human-loving mosquitoes, then, are a perfect, dangerous storm, which combine centuries of climate change, manmade infrastructure and even evolution. The Princeton researchers sequenced the Aedes aegypti genome, and deduced that at some point in the history of Africa, some mosquitoes evolved to take advantage of the human tendency to store water. As a result, all the years later, they were more likely to fly towards the smell of Dr. Noah H. Rose, a co-author of the study, than the Princeton lab guinea pigs.

The implications of this study are sobering — mosquitoes enjoy urbanization, essentially — but helpful, especially as African cities grow. High-growth areas that fit this climate profile should be proactive about identifying human-biting mosquitoes in their area, and removing potential breeding sites before more people get bitten, and potentially fatally sick.

Subscribe here for our free daily newsletter.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.