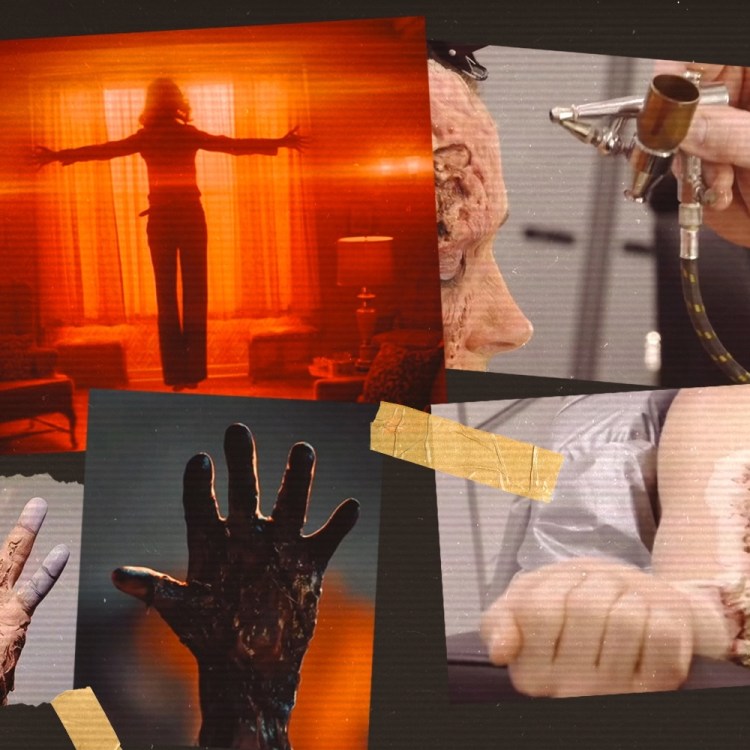

Whether you’re a diehard horror fan, a sci-fi aficionado or someone who prefers more mainstream blockbusters, you’ve likely noticed a growing number of movies and TV shows eschewing computer-generated effects for a more human touch. Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, The Substance, Teacup, Terrifier 3 and even some scenes in Wicked have earned praise this year for their use of practical effects — that is, special effects created physically on set, whether through the use of makeup, prosthetics, puppets, pyrotechnics, animatronics, fog machines, fake snow or all of the above.

It wasn’t so long ago that practical effects were the only effects available. Now, of course, CGI has been around for long enough that it’s no longer impressive. Gen Z audiences who don’t know a time before computer-generated imagery are jaded by its presence, and those of us who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s will always have a sense of nostalgia for the look and feel of the practical effects we grew up watching.

Matthew Scott Kane is in the latter camp. As the creator and showrunner of Hysteria!, a Peacock series about a high school metal band trying to capitalize on the Satanic panic, he used a mix of both practical and visual effects. But as he points out, attitudes toward the two techniques have flip-flopped in recent years.

“In the late ’90s, I can remember movies got greenlit just because they were CGI special-effects spectaculars. That would be the marketing technique,” says Kane. “Now in a world where you’ve had like 500 Avengers movies and Avatar and all of that stuff, the ceiling’s pushed so high that it’s impossible to aspire to that, especially when you’re working in horror and the budgets are low.”

“It’s almost more impressive right now if you can do something like they do in The Substance, which is you’re not using basically any [visual] effects,” he adds. “It’s all in camera. There’s something more mind-blowing now about that than you would ever get in a CG spectacle.”

In a lot of ways, the growing fondness for practical effects feels like the film version of the vinyl resurgence in music. Just like audiophiles prefer the pops and hisses and overall warmer sound of an LP to an MP3, there’s a certain segment of the population who will always find that slick, digital effects leave them feeling cold. Especially after strikes by the Writers Guild of America and the Screen Actors Guild in 2023 fought to address the threats AI poses to their industry, it’s easy to understand why attitudes toward anything computer-generated have shifted.

But Carey Jones, the KNB EFX supervisor on Teacup who has also worked on high-profile projects like on The Walking Dead, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and Predators, says the move back to practical effects actually began nearly a decade ago.

“I think that shift started to happen well before that whole fight [over AI],” Jones says. “I noticed the shift probably eight years ago… Because you’re [adding in digital effects] after the fact, you’re not getting the reactions [from the actors] that you want. So there was this disconnect with the final product. And I think audiences were noticing that and shying away from certain projects that were obviously fully digital.”

The main drawback of practical effects is that crafting them takes time. The most memorable effect on Teacup is an incredibly gory scene in which a woman’s body gets turned inside out, and Jones estimates that one effect alone took “at least five weeks” to put together and involved a “team of artists from 3D artists to sculptors to mold makers and painters and hair and even mechanics.” If you’re someone like Kane who was working on a tight schedule, that simply may not be feasible.

“We didn’t have the benefit of working more practical stuff in because it just does take so much time,” he says. “We did have stunt people there…but to give you a sense of how a day breaks down: If we have the scene, for instance, where Julie Bowen gets thrown through a table, that took us a day. That’s like, at best, $500,000, just to have everyone on set come on and do their job while we spend 12-and-a-half hours lifting the stunt person up and lighting it just right and getting every angle and getting all the coverage.”

In a perfect world, showrunners like Kane would have unlimited time and money to execute their visions. But in reality, they’ll always have to answer to network executives who are most concerned with efficiency and their bottom lines.

“You will always have someone looking over your shoulder and tapping it and saying, ‘But you’re gonna get more out of your day if you just shoot it the artificial way,’” Kane explains. “That is part of the bargain that people have to make right now, which is unfortunate. I wish I could dedicate those days to those things that you care about so much, like making this thing look practical and cool and tactile. But when you’re on a major network, it’s a lot more difficult to push those boulders up the hill.”

Yvonne Strahovski Talks “Teacup,” “Handmaid’s Tale” and Stepping Behind the Camera

The actress also serves as a producer on the eerie Peacock series, which has been championed by Stephen KingJones has felt that effect as well, as he finds himself being asked to produce the same quality of work in a shorter amount of time.

“There’s nothing that we can’t do if we’re given the time to work it out and figure it out,” he insists. “Way back when I first started in the business, you would literally get several months of what we call R&D — research and development. You could just figure out what materials to use, what processes, things like that. Then after R&D, you would shoot test footage of it so that the director and everybody would know how to shoot it. Then you would do your storyboards based on that, camera angles based on that. But now all that’s gone.”

We may be decades beyond the first big CGI effects movie, Jurassic Park — as Jones recalls, “You saw the full CG dinosaurs come out and it was like, all right, that’s it. Pack your bags. Practical effects is done.” — but in a lot of ways, we’re right back where we started, where most productions rely on a mix of practical and visual effects instead of one or the other.

“[Jurassic Park] is probably more than 50% practical,” Kane adds. “I think that is the mixture that we’re heading towards, because, you know, even some of the practical stuff in Hysteria! benefited from light touch-ups with vis effects.” As an example, he cites the practical effects used in a scene where a dog vomits up a heart.

“That worked okay in camera, but with the benefit of vis effects, you can get all this gross sinewy kind of like phlegm coming off of it,” he says. “You can make it pop and be a little grosser and a little bit more impactful.”

Jones agrees. “It feels like visual effects these days, for the most part, it’s more of a tool to help augment something that’s physically there,” he says, “which I’ve always thought that that was the better way to do it anyway.”

But ultimately, as Kane points out, the goal is for the effects to transport viewers into the world of the project, regardless of which way they’re crafted.

“I’ll always want more practical effects artists to be getting work,” he says. “But in terms of myself as a storyteller and whatever I’m working on next, what I think everyone probably strives for is for it all to become more invisible, for you to not even know. ‘Am I looking at something physical? Am I looking at something digital? Or does it even matter?’”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.