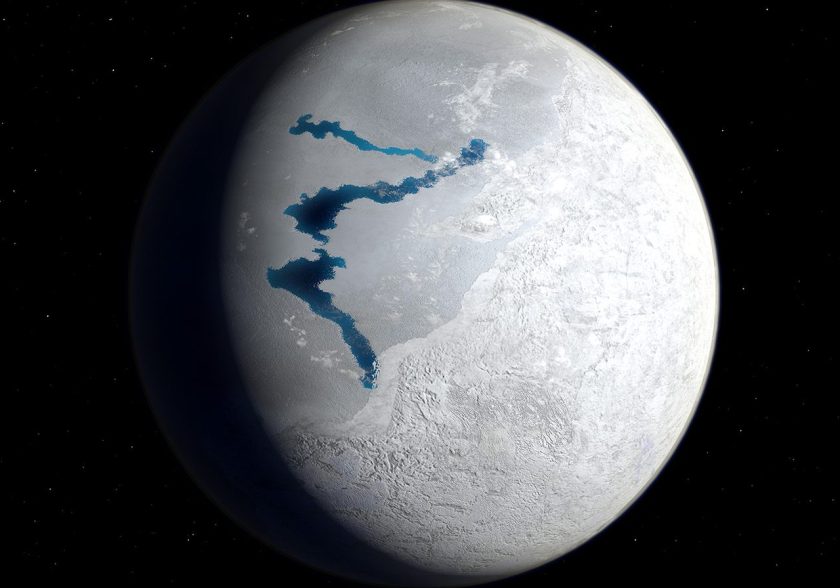

A new theory behind the Earth largest Ice Age, a period dubbed “snowball Earth,” points to volcanoes as the culprit—with a chain of eruptions occurring at the right time and places for the most impact possible.

About 717 million years ago, glaciers covered the entire surface of the planet in ice. Scientists have long debated the root causes of this glacial event, according to Phys.org.

Harvard University researchers now reason the extreme global phenomenon was caused by a period of intense volcanic eruptions—spanning 2,000 miles wide and lasting about a decade—that began just as the planet started to cool.

In their study published in Geophysical Research Letters, the scientists say a cooler climate made it more susceptible to the sunlight-blocking effects of sulfur dioxide spewing from the volcanoes. The volcanic ash hit the stratosphere around the equator where the most radiation enters to keep the planet warm.

As a result, more ice began to form than previously, which in turn reflected more sunlight, cooling the planet down further in a cycle that continued until it reached its apogee.

The new research could shed light on extinctions events and better inform our understanding of how climate change occurs on other planets, too.

—RealClearLife

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.