On an autumn day in London, a handsome man in drab dress sat on a bench in Regent’s Park trying his best not to be noticed. He had a painting hidden beneath his oversized tan puffer.

Passersby hurried to enter the Frieze art fair. But the man just waited and contemplated. He was nervous — so nervous that he had nibbled cautiously on his omelet that morning, concerned a full stomach combined with his nerves might result in something unsightly.

Every little glance he exchanged with a stranger brought a pulse of paranoia. Could they tell by his uncomfortableness that he was hiding something? It’s hard to have a secret without worrying that everyone around you already knows it.

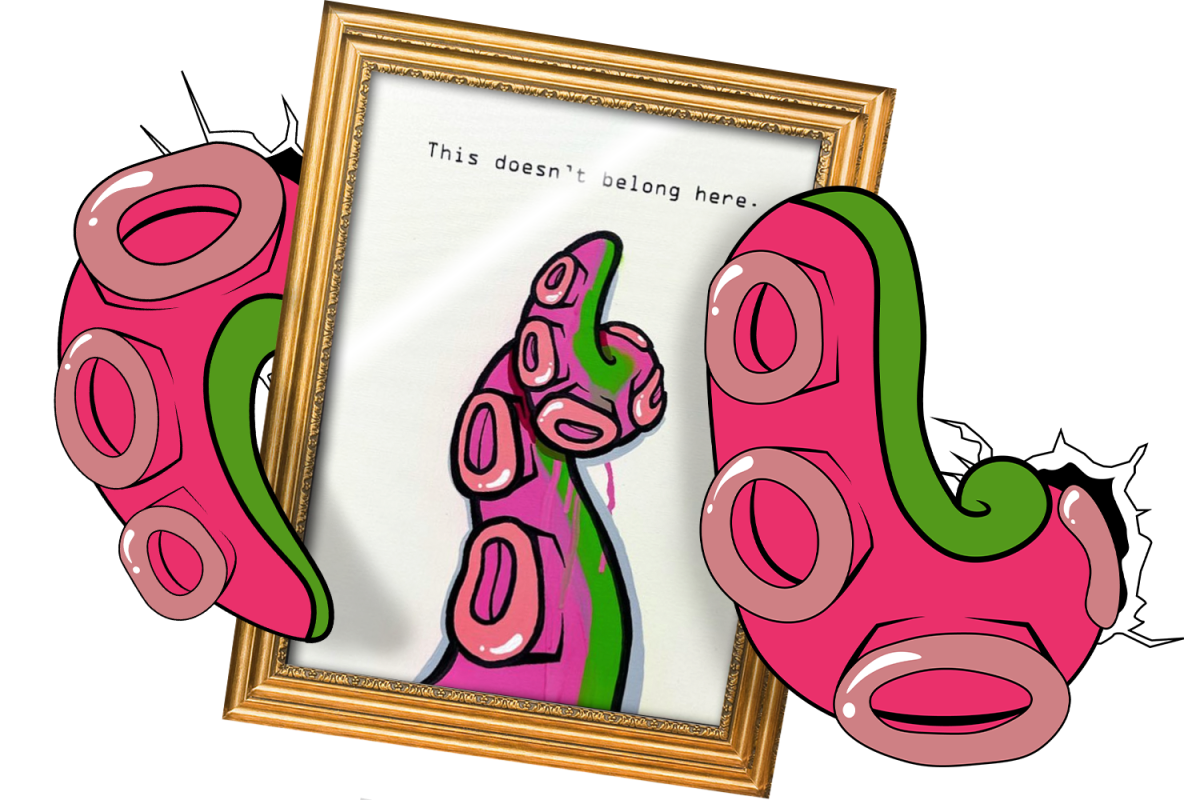

The man, an artist named Cameron Robbie, whose work features tentacles, grew up in the northeast of Scotland, a creative child introduced to painting by his grandmother. Now 24 years old, he has been working as a full-time artist for two years and recently opened a studio in London.

German Museum Hung Painting Upside Down for Over Half a Century

Art history gets weirdWhen we spoke by Zoom, he told me his artistic message is “anticonformative,” which is a mostly made-up word, but that only seems to further his point. “I don’t like this idea that there’s a way you’re supposed to do something.” So, when the biggest contemporary art fair came to London, he figured it was an opportunity to break some rules.

“People are coming in from all around the world,” says Alexis Hyde, a curator and art advisor from Los Angeles. “Out of all of the Frieze fairs, London is the most prestigious.”

Robbie doesn’t speak glowingly of the establishment. “It’s a close knit group of people who go to these [art fairs], and what they say counts. They get to say what is fine art and what isn’t fine art. So what happens if I put a painting on the wall that isn’t, according to them, fine art? Can they — do they even realize? Do they even know what they’re talking about?”

On an 8 by 12 inch canvas he painted a bright pink and green tentacle under the text: “This doesn’t belong here.”

“I wanted it to be some sort of message that was almost like, I’m literally telling you, this shouldn’t be here. And you still can’t tell.”

On the first day of the fair, he and a cameraman went in for reconnaissance. There were more than 160 galleries with space at the fair, and Robbie wanted to pick the perfect spot for his painting. “We found a few that would’ve been easy to do. They were kind of tucked away. It would have been easy to get it on the wall and no one would have seen us. But we thought, if I’m doing something like this, I want to make some noise with it.” Right when he walked through the entrance, straight ahead, there was a white wall with nothing on it. “It’s literally the front wall you see when you walk into the fair.” And the wall happened to be in the Gagosian exhibit.

Larry Gagosian is an emperor in the art world, owning galleries around the globe and representing some of the most recognized talent. “I remembered reading about this guy in a book,” Robbie says in a nonchalant way that would surely make an art connoisseur wince. He had brazenly emailed Gagosian pictures of his work, “saying like, I don’t know, do you want to work together or something? And obviously getting no reply.”

This story did, indeed, make Hyde wince. “Cold emailing Gagosian is not going to get you anywhere, at all. I mean, that’s just not how any of it works, the same way that you can’t just email info@saks.com to hope they’re going to carry your shoe line,” Hyde says. “There are ways to interact and network, and etiquette that goes along with it.”

Robbie doesn’t care. He’s zealous and, mind you, not into rules. One year after attempting to attract Gagosian’s interest, Robbie simply decided to use his wall sans permission.

The night before the reverse heist, he laid in bed thinking about all the possible outcomes. It crossed his mind: “imagine if someone bought it for like a million or something.”

The morning of, he put the painting in a plastic bag then tied it to the coat hook loop on the inside of his jacket. “That way, if they wanted to see inside my jacket,” he gestures with his hands as if unzipping a coat, “there’d be nothing there because it’s on my back.” (The art experts I spoke to noted this was a bit overdramatic. “Frieze security at the door was quite relaxed,” says artist Kinnari Saraiya. Still, she “thought it was quite funny that they sneaked it in.”)

Everything seemed to be going as planned until they approached their chosen wall and saw the layout had been changed slightly. On the recon day, the entrance to the Gagosian gallery was open space filled with people mingling. But now there was a transient installation — a 1960s Indian street vendor inspired bioscope curated by Saraiya — which was being moved throughout the fair each day. What made things worse for Robbie was the U-shaped seating that had been added around the bioscope for its viewing, and the only side without a seat was where the wall was. “Suddenly, there was a seating area where all the benches were facing the wall that we needed no one to look at. So that added an extra layer of difficulty to it,” says Robbie. “We were just waiting for something — I didn’t really know what it was going to be — but something to give a bit of cover.” Then a tour group walked by. “That tour guide, like you couldn’t write it, it was perfect.”

The painting went up and below it he stuck a placard he’d made, on which he included a Gagosian logo with “Not” written in brackets above it. “Again, I wanted it to be like so obvious. I’m telling you, it’s not what goes in here.”

Robbie stuck around for about an hour, watching from a distance. “People just went about it like it was a normal painting, just doing like, normal art people stuff.” Some browsed it closely, some took photos, many just walked right past. “Eventually we realized, like, no one’s taking this off the wall, we’re not getting arrested. Like, we might as well just leave it here and head off,” Robbie says. “So we just left it. And that was it.”

His cameraman cut together long and short versions of the stunt for TikTok. The two videos went viral, together accumulating well over five million views. “I think it’s cute. It’s a cute bit,” says Hyde. “It’s a fun little thing. It’s probably less fun for the people who have the booth and have to clean it up or explain to their boss how somebody snuck in and hung something up.”

For the most part, the reception on social media supports the anti-establishment moral of Robbie’s video. Some commenters commended the reverse heist as art itself. Although others noted the caper derivative. Robbie is not the first to reverse heist an art gallery. Banksy has installed his work in New York museums. Though his reasoning was much simpler. He told NPR: “I thought some of [the paintings] were quite good. That’s why I thought, you know, put them in a gallery.” Several YouTubers have done similar pranks, for fun. A little more in line with Robbie’s stunt, in the sitcom It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Mac tries to put a doodle in a gallery to prove that anything can pass as fine art. The gallerist immediately notices and throws the drawing in the trash.

Robbie seems to have actually pulled it off, at least for a moment, and in an incomparably bigger venue than Mac’s fictional attempt in a small-time gallery. But precisely how long Robbie’s statement lasted is an enduring mystery.

The question repeated the most in the comments section is: “what happened next?” Robbie has yet to answer publicly. That’s partly because he revels in the suspense, but also because he doesn’t really know.

He tried to scheme up some way to steal back his painting. Maybe if he could figure out where it was he could go undercover and pull off a reverse-reverse heist. “I tried getting in contact with Frieze. Just about every possible number online I tried ringing up,” he says. “Most of the numbers go straight to answering machines or they’re not recognized numbers anymore.” He tried calling Gagosian galleries, pretending to be an assistant for Jared Leto, claiming Leto was interested in buying the piece. The employee on the phone said she would circle back but never did.

Hearing this, I became consumed by two questions: How long did the painting stay up? And, where is the painting now? I assumed, as a reporter, I might make better headway than Robbie. But I couldn’t get anyone to speak to me either.

All of my calls to Frieze’s press office went to voicemail. I sent them five emails, and the best I got was a brief reply from an anonymous press official informing me that they “do not wish to comment.”

I emailed Gagosian galleries in London five times and never received a response. I called twice, and both times I was told my emails had been forwarded to their press office but otherwise they couldn’t talk to me. They refused to even provide me with a direct number to reach said press office, but they assured me they would follow up on my behalf. I never heard back. Desperate, I emailed Larry Gagosian three times. No response. I thought, at the very least, there must be one Frieze or Gagosian employee who’d heard some rumor of the painting’s fate. I messaged over a dozen, offering to grant them anonymity if they could tell me anything. I got nothing.

A third question arose: Why won’t anyone speak? Even just to say that they don’t know what happened. Then another crossed my mind: If the painting is still out there, if someone is holding onto it, how much is it worth?

As this keeps me up at night, I like to imagine the tentacle painting hanging above the fireplace in Larry Gagosian’s house in the Hamptons. He looks at it every morning with both admiration and loathing. Maybe, many years from now, it will show up at auction, selling for the million dollars Robbie had wishfully dreamed of on the eve of his reverse heist.

Either that or it’s already in a landfill somewhere.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.