Last year, in an article published by Elsevier — the Dutch academic publisher that’s home to The Lancet and ScienceDirect, among many others — Katie Eve raised the alarm over paper mills. Specifically, academic paper mills — which Eve described as “unscrupulous businesses” known for “preparing academic papers often based on fabricated or manipulated data and submitting them to journals.”

Eve explored the issue of paper mills from a publishing perspective — namely, how exactly does a publisher handling countless academic publications make sure that it’s not publishing sub-par or outright false information? But there’s also another, equally unsettling issue here: getting a sense of just how many scientific papers slip through publishers’ quality control and wind up widely disseminated.

As Richard Van Noorden writes in Nature, that number might be far larger than publishers and academics would like it to be. Citing “[a]n unpublished analysis shared with Nature,” Van Noorden points to a staggering figure: since 2000, over 400,000 published research articles show “strong textual similarities” to the products of paper mills. What’s even more alarming is that this figure is climbing: of those 400,000, nearly 70,000 were published in 2022.

The analysis is the result of machine-learning software developed by Adam Day of the company Clear Skies, known for their use of a digital tool called the Papermill Alarm.

Researchers Uncovered the Science Behind Why Optical Illusions Work

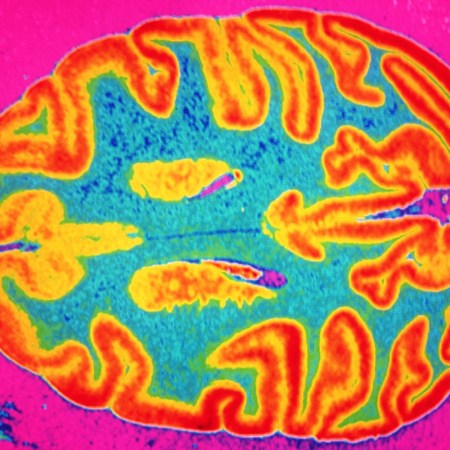

The research involved tricking a computerWhat subjects are these potentially-erroneous papers focusing on? According to the analysis, two areas stand out: biology and medicine and chemistry and material science. If a medical research paper using dodgy science becomes the basis for further study, it isn’t hard to imagine troubling consequences for test subjects.

As Van Noorden explains at Nature, journals are becoming more and more aware of warning signs that a paper might be the product of a paper mill — from suspicious email addresses to citations of other studies that came from paper mills. Still, it’s a problem that’s unlikely to ever go away — and thus, one that requires plenty of vigilance.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.