Mykel Hawke is a former Green Beret who followed his 12 years of service with 12 years in the Reserves. His unique experience and charisma made him an asset to Hollywood as well, where he became a go-to consultant on television and film productions, all while still working closely with the military. He has also authored several books on wilderness survival.

Following his active duty, Hawke worked in several war-torn countries as a military contractor. Here, he describes a deployment to Colombia during the height of the drug war. His story appears as told to Charles Thorp, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Back when I was in the special forces, the only way that you got into military contracting was by word of mouth. During my time in the army and then the Green Berets, I learned a lot of different skills. I started as a radio guy, then went into parachuting and first leadership school, studying everything from languages to tactics. I made myself my own little A-Team. I think because of that I was a good candidate for contracting work.

Not many people really know what military contractors do, and not many movies have gotten it right, so it can be hard to explain. But they are necessary, because the rules of our country and our great Constitution don’t allow for soldiers to be used as security for businesses. But when war happens, infrastructure is damaged. Corporations that risk returning to war zones to build infrastructure are at risk, and regular security is not going to cut it. They need military experience.

I was just coming back from my first job in Azerbaijan when an old buddy came to me saying they were going to Colombia. At that point in time the drug war was really escalating and the bad guys, aka the FARC [Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia], had a dangerous new tactic for making money. They would damage the oil lines, and if the oil companies tried to send people to fix it, they would kill them until they were paid a few millions dollars.

The FARC was also controlling the farmers in the area, threatening their lives to keep them growing cocaine in their fields, all while playing the good guys to the locals by spreading around the dirty money. Because of the politics at the time (it was 1996), the special forces group assigned to the area was not able to get involved with the situation directly. That was because most of their interactions were leading to firefights, and they were worried that it was going to develop into an international incident.

So they needed a group of contractors down there to protect the workers, as well as to help destroy the coke labs that the FARC were involved in. They came to me because they needed a combat search-and-rescue medic who had a good clearance level and the ability to speak Spanish. I always wanted to serve however I could, and I had schooled to be a medic during Desert Storm. It seemed like a way I could really help. I said sign me up.

I was told that I would be living in a jungle basecamp for three months at a time, and that I could only bring one bag. I packed all my medical supplies, communications equipment, survival gear, and personal tactical items. I was living with my girlfriend in Vegas at the time, and flew out of Nevada into Colombia on a tourist visa. The guidance was to lay as low as possible during the flight and at the airport, doing nothing that could get you kidnapped or killed.

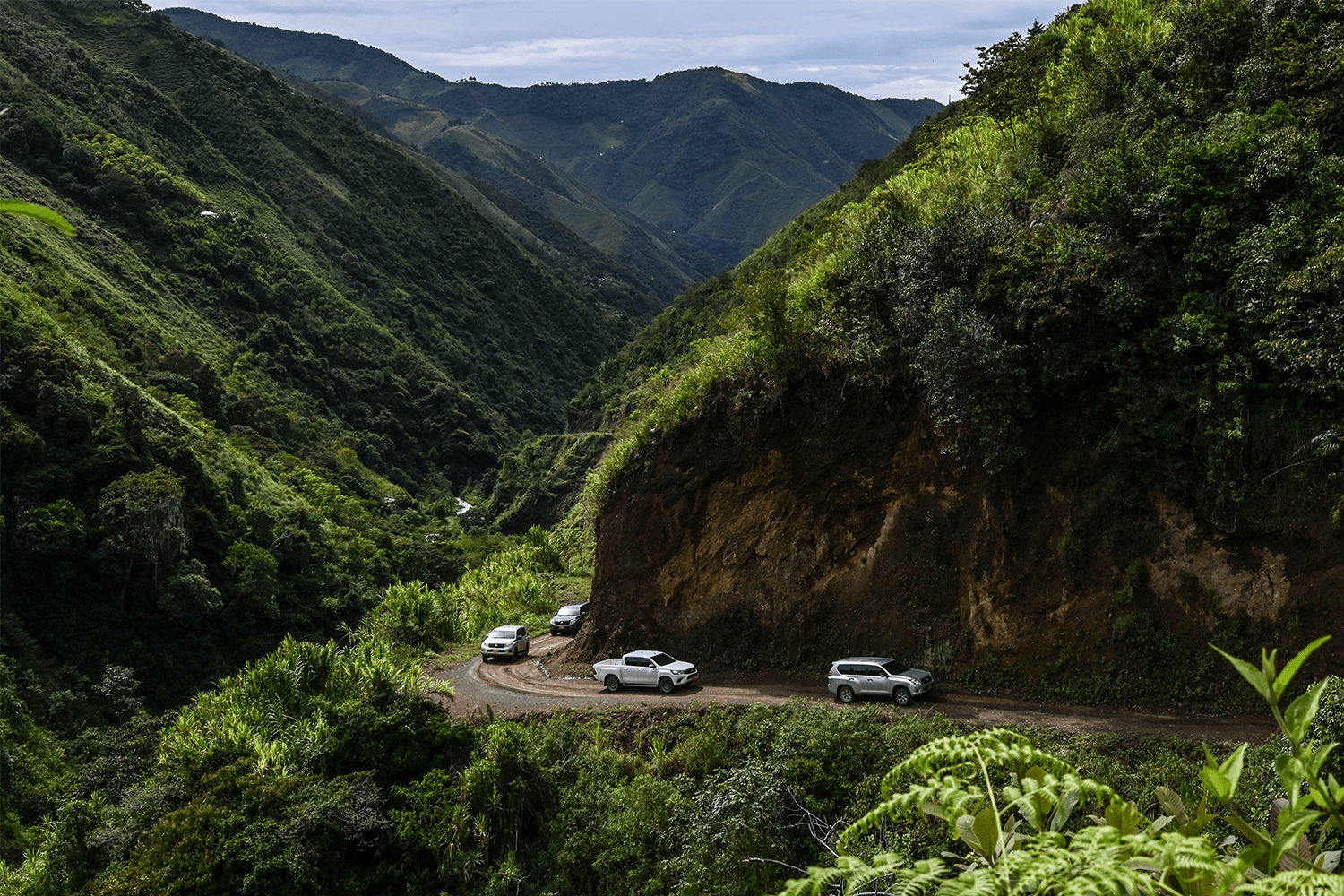

I already am mistaken for being Latino, but I dyed my hair dark just to really make sure I didn’t stick out in any way. Being able to speak the language helped assure that there were no issues during the arrival. Once in the country, I went to my hotel and got a good night’s sleep. Early the next morning I reported to the American embassy, where I met with the staff and got a security briefing. From the embassy, they flew me out in a military aircraft over the mountains, and into the jungle.

I remember expecting that we were going to be living in tents by a river with no hot water, so the little jungle base camp that I flew into was a welcome surprise. There was an airfield where we could get supplies in from the embassy, a chow hall, barracks and even a little spot with a foosball table. There was even a tiny television that only got Spanish-speaking channels. They hooked me up with my military gear and weapons when I got there.

This was before cell phones were what they are now, and they didn’t have the internet on them, so I had brought a little short-wave radio. I would get up early in the morning, before we left for that day’s mission, drink my coffee, smoke my pipe and listen to the BBC. Then, because we didn’t have access to the rest of the world, I would write the news that happened that day on the chalkboard outside so that people had that connection to home.

We spent most of our days flying around the jungle looking for coke fields and labs. When we found them, we would take photos, gather evidence and destroy them. The guys that were running them would shoot at us more often than not, and when they didn’t, it usually meant the place was rigged to explode. On average we were getting into about three firefights a week. Every mission one of the helicopters would have a new bullet hole.

I would come back from missions and sometimes that bullet hole would be right next there where I had been sitting. I would just look at it and think how easily that could have been my head. I am grateful that I was able to make it out of there alive. As contractors supporting the Colombian Army, we got shot at a lot, and a few times we had helis go down. It’s not easy to take a helicopter down with a rifle, but I watched one fall right next to us. Luckily nobody died in the crash, and for hours we were holding them off so that I could evacuate our guys.

There was a base nearby us that was taken over. Their heads were cut off and chucked into the river nearby. During that same time we were getting reports that there were about 500 guerrilla soldiers around us. Of course the embassy being the embassy, they were more concerned about what reports they were hearing from their sources. It was hard to relax at night sometimes, but we would try. During the day we would play soccer or a little guitar I brought, and at night I had a small VHS player where we could rewatch movies like Braveheart.

There were a few vehicles on the base, and occasionally we would take them into town. The closest one to us was San José del Guaviare, about four miles away, and is probably one of the larger towns once you start getting close to the Amazon. Our goal from day one was to have a positive impact on the community, so whenever we could, we’d buy food locally or even on occasion get someone from town to cook for us. The food was great; in the mornings we would have plátanos with rice and beans, and the evenings were similar with some sort of meat.

Of course, on occasion the town would be very quiet when we came through, whether it was for food or medical supplies. Those times you just had the feeling that something was going to go down soon. And there was no question that the FARC had people living in that town that were sharing information whenever we came to visit. But we connected with some amazing people, and you could sense that not everybody who lived there was defined by their circumstances. It was crazy to go through other cities like Bogotá, and seeing how cosmopolitan it was, even while so much violence was happening not far off.

Going back home was a shock in a few ways. I flew back right around Christmas, and funnily enough I got stopped at customs coming back into the country while I had had no issues going to Colombia. I remember the airport security pulling me aside and taking me to the back room. That’s when I showed them my embassy papers and authorization to carry firearms. They were a bit annoyed that I hadn’t pulled them out when I was back in line. But that’s when I explained that if anyone involved with the bad guys saw, I would be dead on my next trip no question.

The next shock came when I was walking around the mall with my boys on Christmas Eve. I was holding both of their hands while they picked out toys, while just a day before a fellow soldier had died in my arms. I looked around the shops to see everyone smiling and enjoying life, not having to see that side of things. For me, that is why we do what we do, trying to help other countries have what we are so fortunate to have, commerce and peace. It may not always be easy, but I believe it’s worth fighting for.

This series is done in partnership with the Great Adventures podcast hosted by Charles Thorp. Check out new and past episodes on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts from. Past guests include Bear Grylls, Andrew Zimmern, Chris Burkard, NASA astronauts, Navy SEALs and many others.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.