Last month, Denso Wave Inc., an obscure Japanese conglomerate that sounds vaguely made up, received a prestigious award from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, the largest association of technical professionals in the world.

Ordinarily, this would be one of those tossed-off bits of corporate news that appears in press releases before sinking to the bottom of the internet archives like a high school lacrosse score. But the timing was noteworthy. After all, Denso Wave, the venerable honoree, was being celebrated in 2020 for something its workers had invented all the way back in 1994: the QR Code.

Given the rapid adoption and even more rapid obsolescence of technology, having a 25-year-old invention showered with laurels seems weird — like if the Recording Academy decided to award the Smashing Pumpkins a Grammy for Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness next January. But that’s 2020 for you. Fanny packs and wide-leg jeans are back, Russia is a menace again, Boomers run the show, and everyone is kinda pissed off at Smash Mouth. It’s like the 1990s all over again.

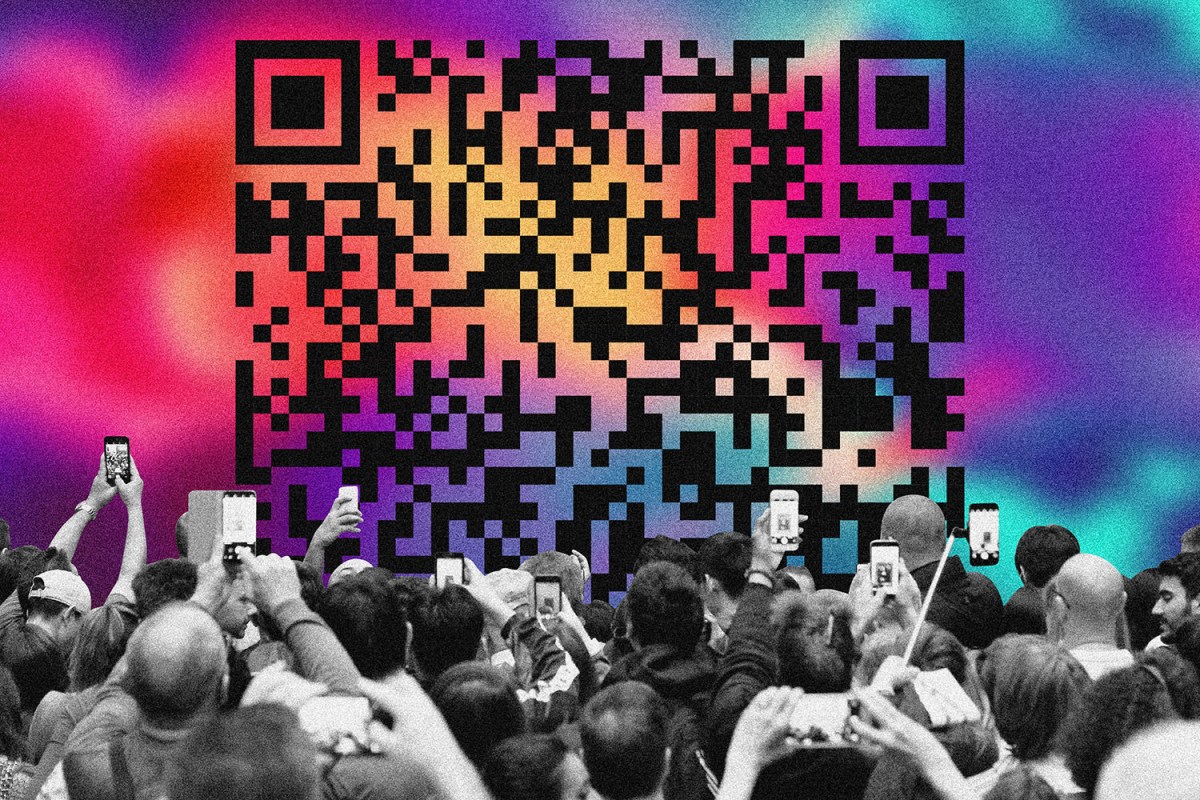

And despite all our rage, the QR code is suddenly very relevant again. After many polarizing years — in which Quick Response codes became a cultural punchline, started to appear on tattoos and gravestones, earned the scorn of Tumblrs and were declared dead — the pandemic has put two-dimensional black-and-white pixel patterns back in our life again, perhaps permanently.

Recently, the payment platform Venmo introduced its very first credit card, which features a huge QR code right on the front. “When you’re out for dinner and everyone throws their card into the folio, the waiter has to split the check between four or five cards,” explained Venmo Senior Vice President Darrell Esch. “Whereas here, I can throw my card into the center, and everybody else can quickly scan my code, link to my Venmo and push the funds to settle.”

The irritating specter of split-check dinners may seem quaint in the era of social distancing, but what the QR code also offers for this surreal time is a way to limit the amount of physical touching strangers and consumers have to do, which is a huge reason why we’re hearing so much about QR codes again. They’re easy enough to use and they help us keep space. Over the summer, the British government released a contact-tracing app using the technology to keep track of attendees at potential super-spreader events, and later this year, CVS will roll out touchless payment using QR codes at 8,000 of its stores. (God willing, the foot-long receipts will remain.)

Another feature of the QR renaissance revolves around the reality that, in spite of American and European dismissals, QR codes have been insanely popular across much of Asia this whole time. In China, consumers buy everything, from street-cart jianbing to Swarovski crystals, using quick response-enabled payments. In recent years, QR codes have accounted for a full third of mobile transactions there to the tune of a trillion dollars in overall sales.

It’s wild to think that after many clumsy debuts (especially in guerilla marketing campaigns), QR codes are finally having their moment — in fancy restaurants, in social justice protests, in doctors’ offices — but the truth is that we had to grow into our QR codes on this side of the world. And sometimes, that takes many years to do.

When Americans first started seeing square-patterned panels, we weren’t initially well-equipped to deal with them. The weak cellular data of the “Can you hear me now?” era often made processing a QR code an infuriating experience that belied the whole point of the technology. And then, of course, there were Apple-induced inefficiencies at the head of the trend. “If you wanted to actually scan one of these things, you [needed] to download a separate bespoke app to be able to do it,” Nicolás Rivero recently vented about the early days of consumer QR codes.

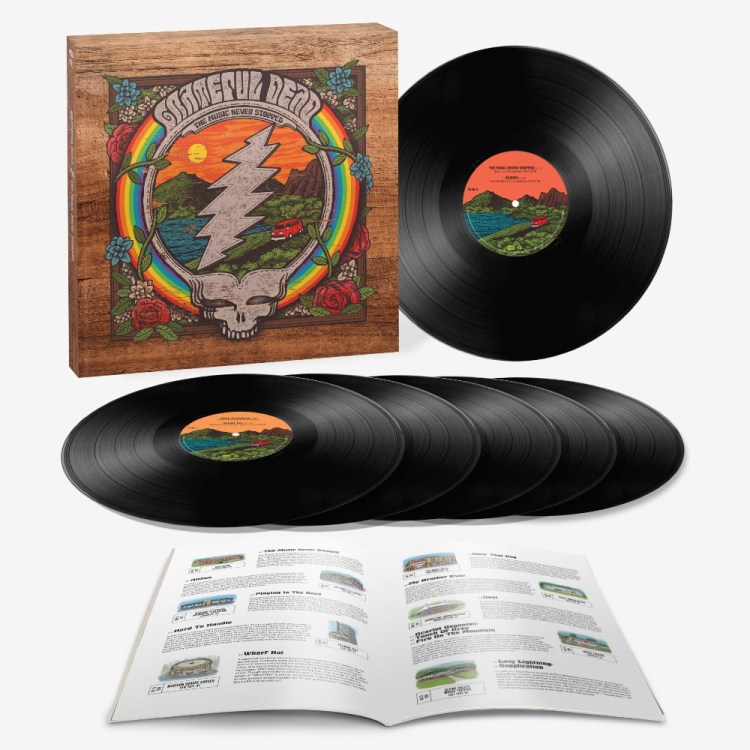

Despite being technologically more prepared, we still have a ways to go before the QR wave means we’ll all be buying street meat or tipping buskers with the whip of a phone. After all, tens of millions of Americans still don’t carry smartphones and tens of millions more are cranky about their tech. And so, like cash, vinyl, or paper books, the old analog ways have a funny tendency to stick around.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.