The video begins innocuously enough with an overflight of a snow-swept desolate landscape, a smattering of buildings in view. The camera then cuts to a military truck and, when soldiers in heavy coats open the back doors, a curious black device is visible.

It’s a cylinder that appears to be about four feet long and three feet in diameter, with dials on one end. The device is picked up by a crane and then dropped slowly, carefully, into a hole in the ground.

Later, the video cuts far away to groups of soldiers, lined up and facing the same direction. Soon video cameras are pointed in the same direction, too. Another shot shows officials monitoring some technical equipment.

Finally, there’s a cut to an unremarkable horizon that, for a second or two seems totally peaceful.

But then the earth suddenly explodes.

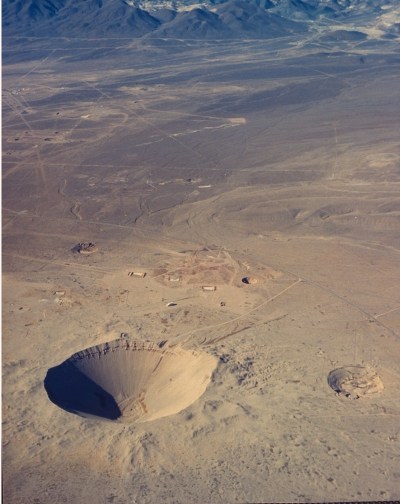

A massive detonation blasts the ground several stories in to the air, creating a wall of ash and debris. What’s left in its wake was an enormous, unnaturally symmetrical crater.

It’s a video, which surfaced a few years ago, of the “Chagan” blast in Kazakhstan near a nuclear test site known as Polygon. The explosion was one of the first “peaceful” uses of nuclear weapons by the Soviet Union on this day in 1965. The idea was to use underground nuclear explosions to create reservoirs out of nearby rivers.

“The crater formed by the ‘Chagan’ explosion had a diameter of 408m and a depth of 100m” and quickly created a large lake, according to a 1996 history of Soviet nuclear explosions.

Following the explosion, radioactivity was detected as far away as Japan, and the U.S. protested the test.

“The Soviets responded that the explosion ‘was carried out deep underground’” and said the radioactivity that made it to the surface was minimal.

As ominous as the idea seems in this era, the idea to use nuclear weapons as a kind of extreme landscaping tool was not a new one. The U.S. conducted more than two dozen similar experiments under what’s known as Operation Plowshare.

“The reasoning was that the relatively inexpensive energy available from nuclear explosions could prove useful for a wide variety of peaceful purposes,” a U.S. Department of Energy document says. “Conceptually, industrial applications resulting from the use of nuclear explosives could be divided into two broad categories: 1) large-scale excavation and quarrying, where the energy from the explosion was used to break up and/or move rock; and 2) underground engineering, where the energy released from deeply buried nuclear explosions increased the permeability and porosity of the rock by massive breaking and fracturing.”

The DOE says using nuclear weapons for such peaceful purposes was considered before the first atomic bomb was ever detonated. The name itself, Plowshares, had its origins in biblical scripture about “ensur[ing] peace by beating swords into plowshares.”

Most of the “peaceful” American nuclear tests – with non-intimidating code names like Gnome, Ace and Sulky — took place in Nevada, but some were in New Mexico and Colorado. They tested how good nukes would be at digging canals and see how carbonate rock was affected by atomic blasts.

The tests continued until 1973 when the U.S. government pulled the plug on Plowshares.

“Many engineering projects did not progress beyond their planning phase and construction was not started. In general, planners were confident that the projects could be completed safely, at least within the guidelines at the times,” the DOE document says. “There was less confidence that they could be completed cheaper than by conventional means and most importantly, there was insufficient public or Congressional support for the projects.”

One Cold War later, back in Kazakhstan, the government has opened Chagan, better known as “Atomic Lake” to tours for the bold or nuclear-obsessed.

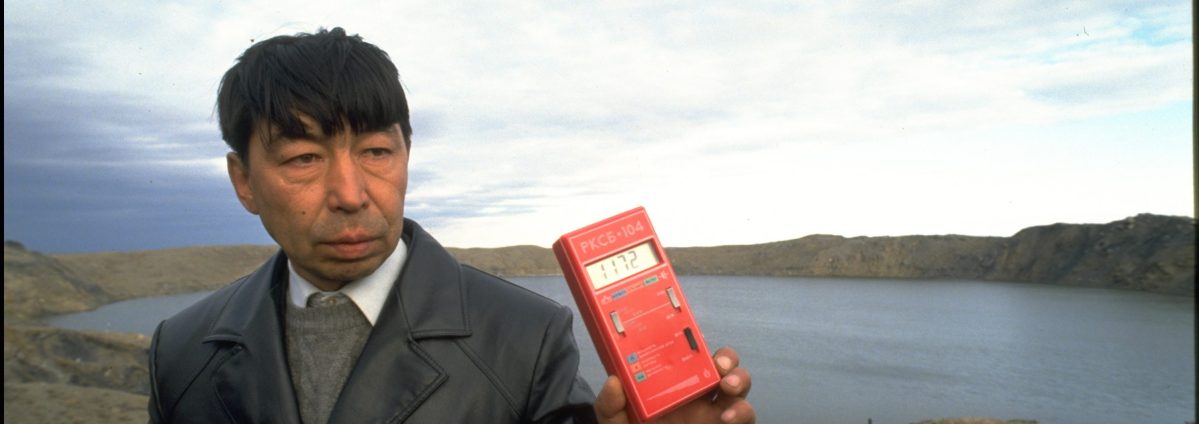

In 2014 a journalist working for VICE visited the site, Geiger-counter in hand.

“The further down we go [into the crater], the higher this needle is going,” the reporter says in a video posted online.

Then the reporter hops in a boat and goes on a casual row.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.