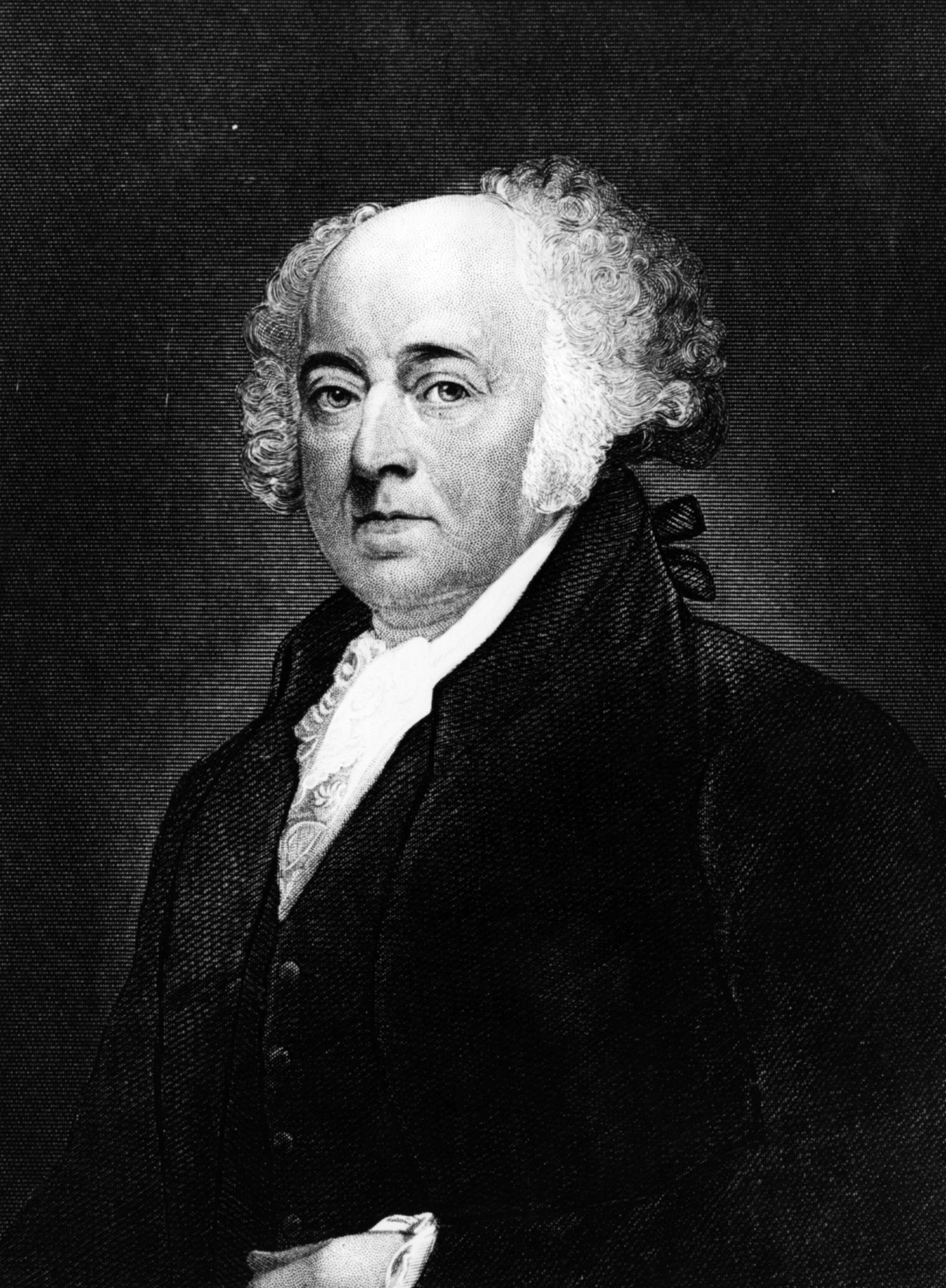

New evidence suggests that the adulterous relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings was originally leaked by none other than John Adams.

In an article for Smithsonian, Mark Silk believes that he’s found written correspondence from Adams that predates James Callender’s exposé of Jefferson’s relationship with Hemings. Callender’s 1802 article in the Richmond Recorder accused Jefferson of adultery and mentioned Sally by name, and historians believe this to be the first direct public acknowledgment of the affair.

Silk, however, points to two letters written by Adams, a political rival of Jefferson, to his sons in 1794, eight years prior to Callender’s article. Silk posits that the letters used coded and/or colloquial language to reference Jefferson’s affair with Hemings. One letter makes reference to Jefferson being “invited from his Conversations with Egeria in the Groves” to chase his presidential ambitions, and the second letter restates this, saying that Jefferson might be “summoned from the familiar Society of Egeria” to run for president.

“Conversation,” it should be noted, was a slang term for sex back then, and “familiar” had a similar meaning, so Adams could very well have been accusing Jefferson of infidelity.

“Egeria,” meanwhile, is a reference to ancient Roman mythology: She is the nymph who tutored (and slept with) Numa Pompilius, a philosophically inclined widower (like Jefferson) who succeeded a ruler drawn from the military (again, like Jefferson). Adams was certainly well-educated enough to make those allusions (which were more widely understood back then), and Jefferson’s affair was allegedly known to select members of Virginia society anyway, so it’s very possible that he was making a somewhat highbrow joke about it with his sons.

Adams also dismissed Callender’s remarks in other correspondence, writing to Joseph Ward in 1810 that “I believe nothing that Callender Said, any more than if it had been Said by an infernal Spirit.” Thanks to Silk’s inquiries, whether Adams was being genuine or just covering his tracks to be polite has been thrown into question.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.