Nathan Graves, general manager of the 13-year-old Nashville Nightmare haunted house, admits it was a hard transition to management. “People don’t take you seriously if you’re dressed like a clown,” the 38-year-old says.

Graves is not being figurative.

It’s mid-September, the Tennessee heat recently breaking, and we’re seated on peeling couches in an open room deep within the Nightmare complex on the backside of a mall. Graves crosses one leg over the other, relaxed in faded jeans and his company’s merch T-shirt, his red skin evidence of long days in the summer sun setting up Nightmare’s outdoor midway, cursing as a 30-foot skeleton resists its head being attached. He says it wasn’t his employees not taking him seriously — in haunted house culture, it has a certain logic that your boss would be dressed as a clown. No, the reason Graves now dons casual attire during operating hours while carrying a faux head painted as his alter ego, Jinx, is, paradoxically, his professionalism. (And yes, Graves is his real last name, and yes, due to his job, he is asked that a lot.)

“Something serious happens, customers call the manager, and I would come over fully dressed as a clown,” he says. He pauses to let the scene sink in. “So I’ve dropped that.”

Back in 2014, when Graves took a seasonal job at Nightmare as a “standard ghoul,” he was overseeing an HVAC warehouse and floating between the various trades. But the company scouts talent from within. “Once somebody sees wealth in you, they continue promoting,” he says. He took a full-time position in 2017. “If a clown like myself can make it, anyone can.”

Halloween is the haunted house industry’s biggest season of the year (yes, they have multiple seasons), but in the 21st century, it’s moved far from its mom-and-pop roots into an international celebration of spook that employs tens of thousands. “Nobody trick-or-treats except for the United States,” says industry pioneer Larry Kirchanr, 53, whose Blacklight Attractions operates three “haunts,” as they’re called by insiders, in the St. Louis area. “Halloween in China, Japan, Germany or England, it’s just haunted houses. It’s been embraced worldwide.”

InsideHook caught Kirchanr mid-morning three days after a scheduled interview, and between yawns — it’s been a grueling setup process for everyone as they approach opening day — the 35-year industry vet recounted the sea change he’s seen since he was a 19-year-old trying to cadge a free ticket. In the ’90s, the houses were smaller, the technology limited to strobe lights and black plastic, and the owners more side hustlers than CEOs. Kirchanr remembers one of the most common question between attendees of the annual Halloween and Attractions Show was what the other did for work, the understanding being that no one could make a career out of a business that operates one month per year. “Their haunted house was their hobby,” he says.

But hyperlocal wars in the aughts between small, independent houses, waged by scorched earth marketing campaigns and the nascent internet, produced sole survivors over larger territories. They expanded into the vacuum, and many transitioned from the traditional set-up/teardown outdoor model to indoor spaces, where the emphasis switched from portability to creativity. These haunts became both bigger and more complicated, bolstered by Hollywood innovations like LED lights, digital soundtracks, airbrushing, silicone masks and high-tech animatronics, all of which were manufactured and sold by a burgeoning support industry. “Back then, if you wanted a bloody body, you had to make it,” Kirchanr says. “Everything’s changed.”

Without the aid of an industry trade group, it’s difficult to calculate the number of haunts across the country, both currently and historically. But Kirchanr says its impact can be felt in other categories that are more measurable. Halloween decorations, which the National Retail Federation estimates will reach $3.9 billion in 2023, have been significantly advanced through haunted house tech. “Home Depot, Lowe’s, Spirit Halloween, all of them sell these animations now,” he says, referring to the electronic monsters that scare the shit out of kids as they reach their hands into a candy bucket.

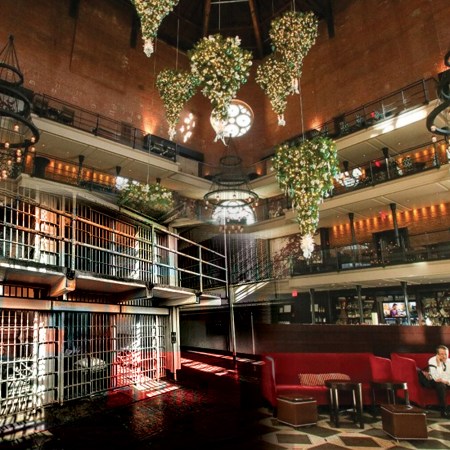

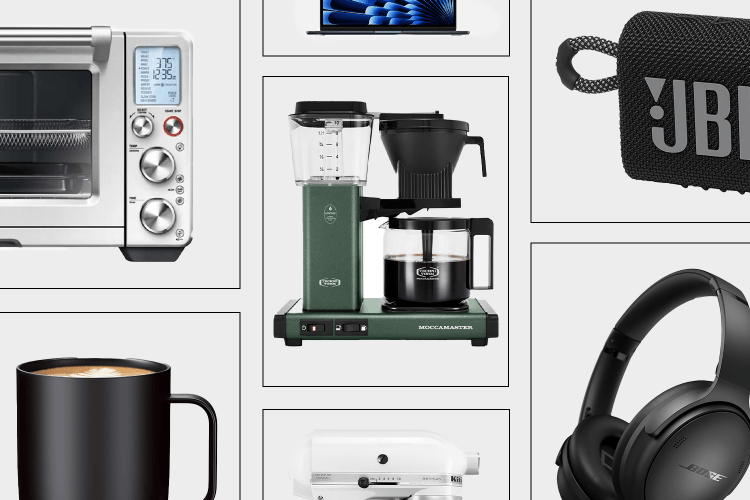

But the biggest change in modern haunts can be measured in amenities. Nightmare is comprised of four separate houses, which span between 10,000 and 25,000 square feet each and take anywhere from eight to 25 minutes for a walkthrough. But while patrons decide on which to enter next, they snap social media photos in a midway, purchase concessions and a la carte mini-experiences, and access a speakeasy-style hidden bar with a signature cocktail. And for many across the country, the exit is always through the gift shop, which has moved far beyond branded T-shirts and hoodies. Kirchanr’s retail shops have become their own attraction, with everything from goth purses to life-size Annabelles for $450. “The only way we could make the retail store bigger was to take space out of the haunted house,” he says, “and that’s exactly what we did.”

But even with all of its advancements, the industry has maintained its core of a good scare that continues well after you return home. Chris Stafford, 51, was invited by a high school friend to work at his parents’ haunted house in his youth, and he continued the annual tradition until a career in banking became too busy to allow for it. “Haunted houses were how we celebrated Halloween every year,” he says.

Today, Stafford’s Thirteenth Floor Entertainment Group owns 18 haunted houses across the country from Los Angeles to the Southeast, which includes Nashville Nightmare. With 85 full-time employees and around 3,500 seasonal hires, his conglomerate is one of the biggest players in the U.S.

“I already know what everybody’s doing every day on Facebook or Instagram. So we have to go out and do something unique together and share that experience,” he says. “That’s really benefitting our industry.”

While haunts themselves are doing well, one of the industry’s biggest challenges is space insecurity. Few own the property on which they work; most rent within close proximity to metropolitan centers, and therefore, as cities like Nashville undergo population booms, it becomes harder and harder to identify and secure locations capable of housing the modern haunted house. Despite Nightmare’s 13-year history in the same space, a recent development plan places a parking garage directly on it. But Stafford accepts even that. “That’s the nature of this business,” he says. “You’re always looking for the next location.”

The Scientific Argument for Letting Kids Eat All the Candy They Want This Halloween

They’ll be better off in the long-term for it, counterintuitive as that may seemIt’s cliché, but Stafford emphasizes that it’s not his houses’ cutting-edge tech, marketing wizardry or ingenious add-on experiences that make his and, by extension, others’ haunts successful. The key to success, he says, is people. It’s guys like Graves, who found purpose and a career dressing as a clown while managing a diverse team recruited from a tight labor market. It’s guys like Kirchanr, who wanted to be a filmmaker but instead helped build haunted houses for most of the amusement parks in North America. And it’s guys like Ott Denney.

Denney, 52, is Nightmare’s makeup director, a job he learned onsite over the past 13 years. Heavyset, with half-sleeve tattoos and a septum ring, he is a family man with a full-time job in printing and a youth ministry position at his church. But during the Halloween season, he manages a crew of eight, who combine to airbrush pallid skin on 70 to 80 actors daily. He eats dinner driving cross-town after his eight-hour corporate shift so that he can be first onsite and turn on the air conditioning. “I don’t play golf. I don’t go out. It’s a hobby and an outlet,” he says. “I’ve just been lucky to have an understanding wife.”

In the haunt’s mask room, surrounded by disembodied, sterilized heads of all shapes and types, Denney says it was the family aspect of the environment that first attracted him. “That’s part of the reason why I still do it: to give back.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.