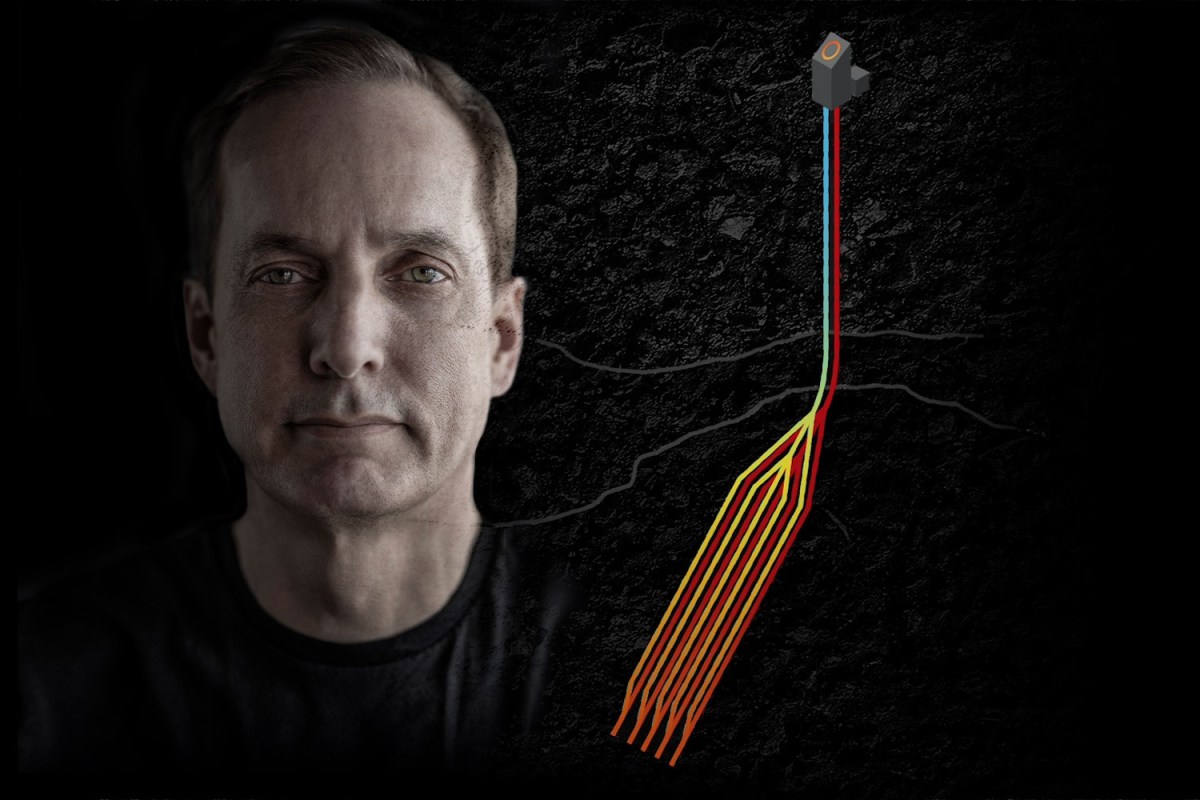

John Redfern might just save the planet. Chances are that you’ve never heard of the soft-spoken, middle-aged Canadian entrepreneur. For much of his career, he was busy with his startup in Shenzhen, China’s free-trade region, using data analytics to recommend the best places to open thousands of stores for companies like Nike and McDonald’s. He only got into “the entrepreneurial thing” by accident.

“I think a lot of people like me like the idea of starting their own business, but it’s always a question of where you begin,” Redfern tells InsideHook. “Like a lot of entrepreneurs, I got into it when I lost my job, got divorced and saw 9/11 happen all within two weeks of each other. It’s easier when you’re pushed out of the nest.”

Few might consider that his latest startup, Eavor, co-founded in 2017 with Paul Cairns, is out to do anything easy, since the objective is no less than solving the energy crisis — the need to find clean and dependable sources as we necessarily move away from fossil fuels and their impact on the planet.

“I haven’t had to raise half a billion dollars on the other startups, let’s put it that way,” he laughs. That kind of cash, and more, is needed because Eavor (pronounced “Ever”) has reinvented the idea of drawing heat energy from the ground — from the rocks, miles down, super-heated by the Earth’s core, where temperatures are comparable to those on the surface of the sun, and which would, were we not dependent on our star, outlast it.

Yes, that’s the geothermal energy that so many have dismissed as a source of green energy, in favor of solar and wind power, despite all the problems with those sources.

“The thing is that we’ve had at least two false dawns when you might have thought geothermal would be the next big thing — and one of those was a hundred years ago. It’s a case of ‘could have been a contender,’ but never winning the big title, and that tends to dampen enthusiasm somewhat,” Redfern, the president and CEO of Eavor, says. “Geothermal energy all seemed too dependent on certain geological conditions, or there was the sense that it wasn’t scalable, or that the technology wasn’t available. That’s why even those who should have liked it, oil companies — which for a decade have been told they’ve got to go green, and who have all the necessary talents and assets and information — have been like the kid who doesn’t want to eat his peas. They just haven’t been interested.”

Much like Thomas Edison rethinking the lightbulb, Henry Ford the motorcar and Sam Walton inventory control — all working with established but unfulfilled ideas — Redfern and Cairns look set to be, say, the Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak of hot water.

Carbon-Neutral Fuel Sounds Like Fantasy, Zero Petroleum Shows Otherwise

We spoke with F1 veteran Paddy Lowe about his new venture, which he hopes is part of “a complete transformation of world energy”Eavor’s “Big Radiator”

Their idea is deceptively simple. Traditional geothermal technology has to target an aquifer, and then use a form of fracking, forcing water into and then out of the very hot permeable rock underground, creating steam to drive a turbine to generate electricity, but losing about 50% of the energy in the pumping process.

Instead, Eavor’s plan is to drill two eight-inch-wide wells down several miles, then drill laterally some more miles and connect them, thus making a huge closed loop. Then, through conduction, they’ll let the water flow through it, the large surface area of the bores being super-heated by the surrounding rock. That’s one loop of maybe 10 loops in a major plant.

“It’s just like a big radiator,” as Redfern describes it, making the hard-to-do sound very simple.

In another sense, he says, it’s the reverse of one of the oil industry’s ways of extracting oil sands, in which drilled wells allow heat to be injected underground to loosen the sands and allow the oil to be removed.

Eavor’s “closed-loop’ system — the Eavor-Loop — has been working towards full-scale operation for a few years. The company launched Eavor Lite, a small-scale proof-of-concept plant in 2019, and followed that with Eavor Deep in New Mexico late last year, which proved the technology could be used in, for example, granite rock and super-high temperatures, environments that the traditional oil and gas industry avoid.

Now, among several Eavor projects in the works, the most advanced is a $325 million Eavor-Loop under construction in Bavaria, Germany, on the site of a decommissioned power plant and funded in part by a grant from the EU Innovation Fund. Drilling began this July, and it’s expected to take three years to produce four loops — amounting to 150 miles of wells in total, 2.5 miles deep and coping with temperatures around 302 degrees Fahrenheit — though power is expected to come online in October 2024 when the first loop is complete. With that, Eavor expects its idea to be commercially proven.

“That’s a lot of drilling,” notes Redfern. “Never since Bruce Willis and Armageddon has there been the potential for the world to be saved by a bunch of drillers drilling holes.”

The New Era of Geothermal

It seems it was precisely because Redfern was not previously in the drilling business that he thought about geothermal energy in a fresh way. His interest was prompted by the Canadian government’s plan to spend some $80 billion CAD decommissioning oil wells. Surely, Redfern thought, there was something better that could be done with that money and all that infrastructure, other than just scrapping it.

“Like all good entrepreneurs, we got into [our subject] with some degree of naivety, because if you knew all about geothermal energy from the outset, it’s such a mountain you might never try to climb,” he recalls. “All I had was the ‘man on the street’ knowledge of geothermal. But we started just by asking, why isn’t geothermal a bigger success? What’s holding it back? I don’t think we’ve succeeded because we’re particularly brilliant, but because we started from a different standpoint and asked different questions that hadn’t been asked before.”

“People forget that if a solution is too obvious, there’s probably not a ripe opportunity for making billions. People would have done it already,” he adds. “You need something that looks ugly but actually isn’t. Our idea looks similar to those tried before: you get heat out of the Earth. But it actually changes everything [about the process].”

Redfern says he had his eureka moment when he met with an executive from Shell, who told him that the oil industry was never going to be interested in pursuing geothermal energy. This executive then produced a list of 10 reasons why not. Redfern and Cairns looked at the list and realized that their closed-loop approach would, theoretically, answer all of those objections. That was encouragement enough to pursue their idea. “And you’ve got to love it, but this Shell executive’s business card read ‘Black Swan Detector,’” Redfern chuckles.

Never since Bruce Willis and Armageddon has there been the potential for the world to be saved by a bunch of drillers drilling holes.

John Redfern, President and CEO of Eavor

“Of course, the big thing for any entrepreneur then is the need to place your bet,” he says. “You can’t be cautious about it. The bet we took was that the future of geothermal will be big and closed-loop. The clear target then is how to make it work, patenting your progress along the way. And then how to make it commercial. Ninety percent of the time as an entrepreneur, you hit a dead end with these ideas. But every once in a while you get one like this and you have to run with the ball and see it through to the end. The ball just keeps seeming to bounce in Eavor’s way.”

Redfern concedes that on this occasion the timing has been just right; had he rethought the closed-loop approach a decade ago, it would likely have met one of those dead ends, either economically or technologically. The tech that allows the drilling of these huge, precise “radiators” is improving all the time, and now you can drill up to 5.5 miles deep and up to 750 degrees Fahrenheit, in no small part thanks to Eavor’s pioneering of insulated drill pipes.

“That’s more than enough [for geothermal to be a practical option],” he says, “though it’s always better for any geothermal project to be able to drill hotter, faster, cheaper, deeper.” While there is some irony in the fact that Eavor is, broadly-speaking, repurposing — and in some cases reimagining — oil and gas industry expertise and technology, some of it quite recent, Eavor continues its push its own ideas to bring further efficiencies to its drilling and heat extraction. Small wonder that fossil fuel companies are now among Eavor’s investors.

Proving the Closed-Loop Concept

Advanced geothermal has the potential to gain interest partly because the unfortunate realities behind wind and solar are starting to set in. Redfern says these power sources got all the attention of the green lobby “because they’re cheap and fast, so when you start decarbonization they’re [the technologies] to put in.” But people are starting to notice not just the intermittence of their power delivery, but just how much land wind and solar require, “which is fine if you’re in the middle of Nevada, nobody will notice, but it won’t work for, say, Singapore or much of Europe,” he argues.

What geothermal offers is green power that can go where wind and solar can’t, and can be what’s known as “dispatchable”: geothermal energy extraction can be turned off or on as demand requires. The heat is always there; it’s a matter of simply pausing the flow through the pipes. That’s going to be very useful in addressing one of the key reasons that our use of fossil fuels, gas especially, goes on apace: heating our homes. This heat is needed as and when consumers demand, and the power source behind it needs, ideally, to be relatively near to urban centers, in a way that makes intermittent, large-scale and, some say, ugly wind and solar systems unsuitable, especially given current battery technology.

“What’s also key is the ‘financeability’ of the project,” Redfern says. “With traditional geothermal, or oil and gas, you need a high rate of return because it’s risky — you don’t know what you’re going to produce. If they do produce, you don’t know when they may rapidly go into decline. [With Eavor’s system], before we even drill we know what the output will be. To a banker, we don’t look like oil and gas.”

Amid global conversations around the need to reinstate nuclear power stations, or to find some wonder technology to solve the climate crisis, Redfern is saying that the wonder technology is already here. Chatting at parties, he says that people do ask him why they haven’t heard of it; whether it’s all just too fantastic. He assures them it isn’t, but that people like him have just been butting up against geothermal experts who for decades have been taught that closed-loop systems don’t work. “You just have to convince one person at a time,” he says.

This isn’t to say there are not hurdles, though some very high ones have already been vaulted. Funding remains a perpetual problem, even if Eavor has recently raised another $182 million through its latest equity round. The more advanced the project, the more Eavor faces the possibility of delays or unforeseen costs that scare off investors.

This is, after all, a complex and expensive business — in the same way that the competitiveness of wind and solar was unclear in their early days — which is one reason why the countries Eavor is pushing ahead in, Italy and Japan among them, are also those willing to pay top dollar for dispatchable clean energy. It’s new, too, and inertia is always a challenge for startups — it needs major players and politicians to get behind it. And then there are competitors: Eavor is patenting like crazy, but there’s nothing to stop another energy company exploring similar closed-loop methods. The company is making great strides, but it isn’t out of the woods yet.

The Naive Hope That Oil Companies Will Fix Climate Change

The mistake of choosing Sultan al-Jaber, the head of the UAE’s state oil company, as president of COP28 has become clear. It should have been obvious.Over the next few years, while the German project may prove convincing to many, the Eavor-Loop has the potential to be transformative not just of our energy supply, but of our geopolitics. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has recently highlighted the fragility of energy supplies and underscored the push for energy independence in many nations. But even in a post-fossil fuel world, Redfern argues, demand for the resources that are required to build turbines, solar panels, batteries and the like will still tilt power to some nations over others, driving instability. In his estimation, that all goes away with geothermal energy.

“It’s long been the case in the past that energy sources all required something special, and whoever controls those scarce resources tends to have the upper hand,” he says. “With geothermal, wherever you are, all you have to do is drill down deep enough and there’s heat. There’s no rare resource involved. Our technology is such that any country or region that wants energy independence can have it.”

If that truly is the case, how does Redfern stop himself from shouting from the rooftops about his breakthroughs? He is fairly understated about it all. Of course, if the Eavor system takes off, it’s likely to make him exceedingly rich, but he and Cairns will also have achieved something of historic, seismic proportions, like the two Steves before them. Geothermal now accounts for less than 0.3% of the world’s energy. How long before it accounts for 1%? 10%? More?

“Technically we’re confident — any tech like this takes longer than expected to get into truly commercial territory, but the building blocks are not brand new and we think the system is proven,” he says. “The financial interest is there, and I think everyone likes the ‘swords to plowshares’ story, the delicious irony of this ultimate green energy technology being born out of the scariest of the oil and gas technologies.”

“I think I can speak for everyone at the company that we’re all pretty excited with the mission. I’m somewhat older now, but still get excited about this. It’s even the first of my startups that have got both my dad and my son excited about it too. And that’s a rarity, to be sure.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![Ulysse Nardin BLAST [AMOUREUXPEINTRE]; Shinola Circadian Monster 36; Chopard L.U.C LUNAR ONE; Tudor Black Bay Chrono Flamingo Blue; Mark II Fulcrum 39](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Watch-Header.png?resize=750%2C500)