Locals called it “the butchers shop.” The letters languishing on the dreary brick edifice spelled a different name: Lincoln Hospital. It was the primary source of healthcare for residents of the South Bronx. Shortly after 5 a.m. on July 14, 1970, a U-haul truck rumbled innocuously through the gate.

The building had been condemned some 25 years earlier, deemed unsafe for human habitation, but city officials ultimately decided to keep the hospital open. Reports of unsanitary conditions and medical malfeasance proliferated over the years. City Hall responded with inaction. For the young men and women riding stealthily in the cargo bay of the U-haul, enough was enough. July 14 was a day of action.

They were members of the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican liberation group that sought to protect and empower their community. For a long time, they had been trying to get the city to do something about the inhumane conditions at Lincoln. They had recently set up a “complaint table” in the emergency room lobby, and in one month documented more than 2,000 complaints from patients, including reports of babies getting bitten by rats. All of the complaints were sent to local officials. None of them were addressed in any meaningful way.

The door of the U-haul swept open and the Young Lords streamed into the hospital. They were unarmed yet unyielding. Within 15 minutes they seized control of the entire building. “It was an occupation that came straight out of the Normandy invasion,” said Felipe Luciano, one of their leaders. As the sun rose, the Puerto Rican flag flew over Lincoln Hospital.

Scores of blue-shirted policemen arrived. Emissaries from the Mayor’s office followed. The Young Lords finally had the city’s attention. One press conference and 12 hours of negotiations later, they peacefully ceded control of the building. Officials agreed to address the most serious complaints and gave the Young Lords permission to run community programs under the supervision of hospital physicians. This is how the Lincoln Detox Center started.

Dope is Death, a new documentary from filmmaker Mia Donovan that’s now available on VOD, is a story about community health and radical politics. In the late 1960s, New York became the epicenter of America’s heroin epidemic. Cheap junk flooded the streets, turning the South Bronx into a zombie hellscape. Crime skyrocketed. The ravaged community could barely function, let alone defend itself against systemic injustices.

“You don’t wanna fight when you’re on heroin,” Luciano says in the film. “You just want to sit and nod yourself into oblivion.”

Fighting, in a political and direct-action sense, is what the Young Lords and the Black Panthers had in mind. One of the most important and successful elements of Donovan’s film is how it counters official narratives that have shaped public perception of left-wing liberation movements.

“A lot of these groups were criminalized,” Donovan tells InsideHook, “and the criminalization made them look dangerous. It erased the legitimacy of the amazing programs that they were creating to provide for their communities.”

In 1969, J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panthers “the greatest threat to [the] internal security of the country.” This characterization stoked white suburban fear and prompted many Americans to see the Panthers as violent extremists. What people didn’t see, however, were initiatives like the Free Breakfast Program, which fed 20,000 children before school every morning, or the various “survival programs” that provided food, clothing, transportation, daycare, healthcare and legal advice. Beyond building social infrastructure to strengthen their neighborhoods, the Black Panthers sought to eradicate insidious threats.

“Before the quote-unquote war on drugs, they were working to keep drugs out of their communities in the late ’60s,” Donovan says. “And they were. They’d confiscate heroin from drug dealers because the cops wouldn’t. They understood that if they were to call the cops, the cops would just take the heroin and then sell it back into the community to make a profit.”

For the film, Donovan compiled an impressive collection of historical footage. One of the film’s most impactful clips shows a group of Black Panthers destroying bags of heroin in the street.

The Young Lords and Black Panthers saw the opening of Lincoln Detox as a chance to mount a more systematic attack on the heroin epidemic. They were distrustful of methadone, the FDA-approved maintenance drug that essentially swapped one addiction for another, so they introduced their own treatment: acupuncture.

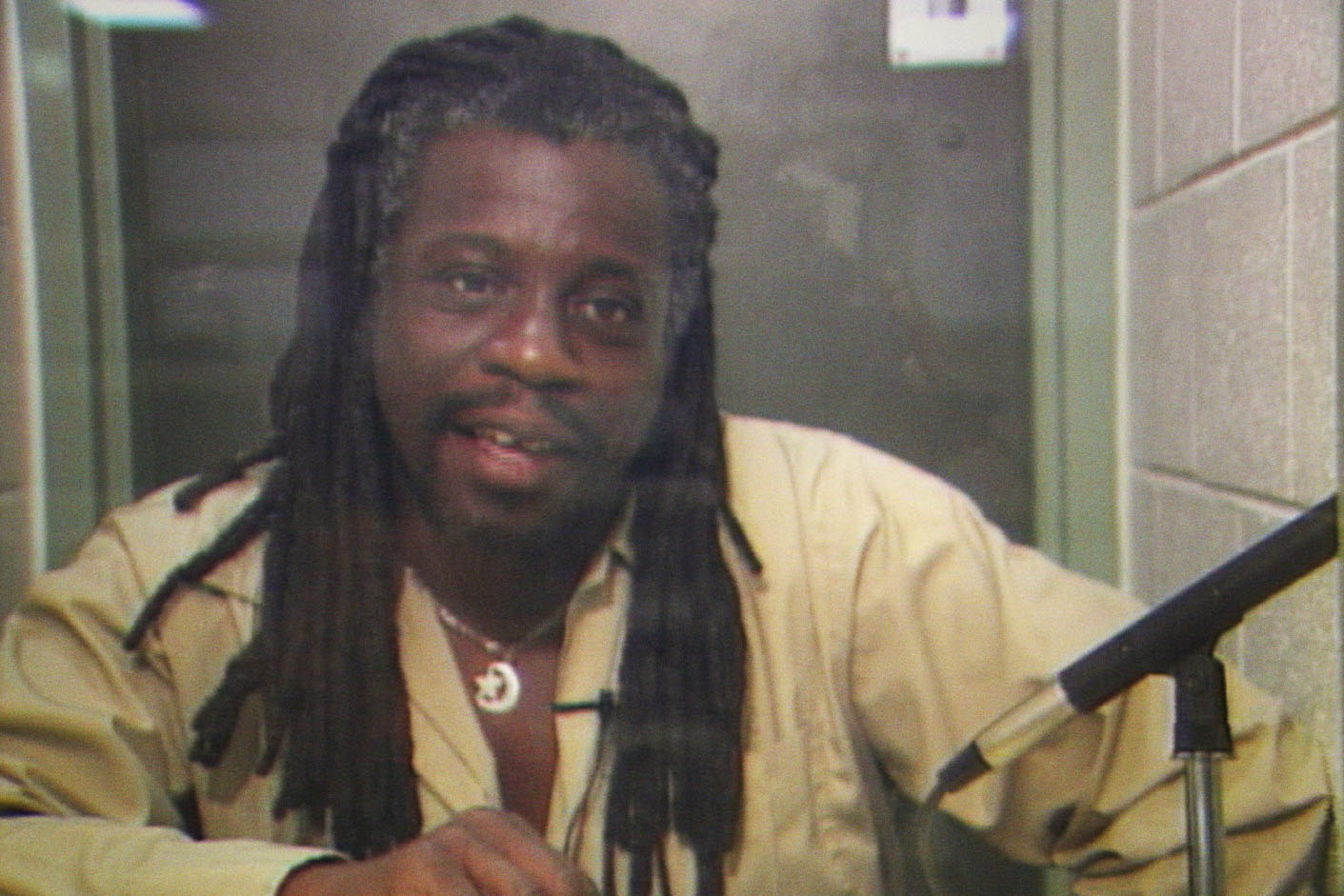

The idea came from Mutulu Shakur, a rising leader in the broader Black Nationalist movement. Shakur was only 20 years old in 1970 but his wisdom and political consciousness belied his youth. Life had taught him that state institutions did not function in the interests of Black people. As a boy, he helped his blind mother struggle to navigate the broken social-services landscape. As a man, he advocated for self-determination. Black communities, he argued, should control the institutions that impacted Black lives.

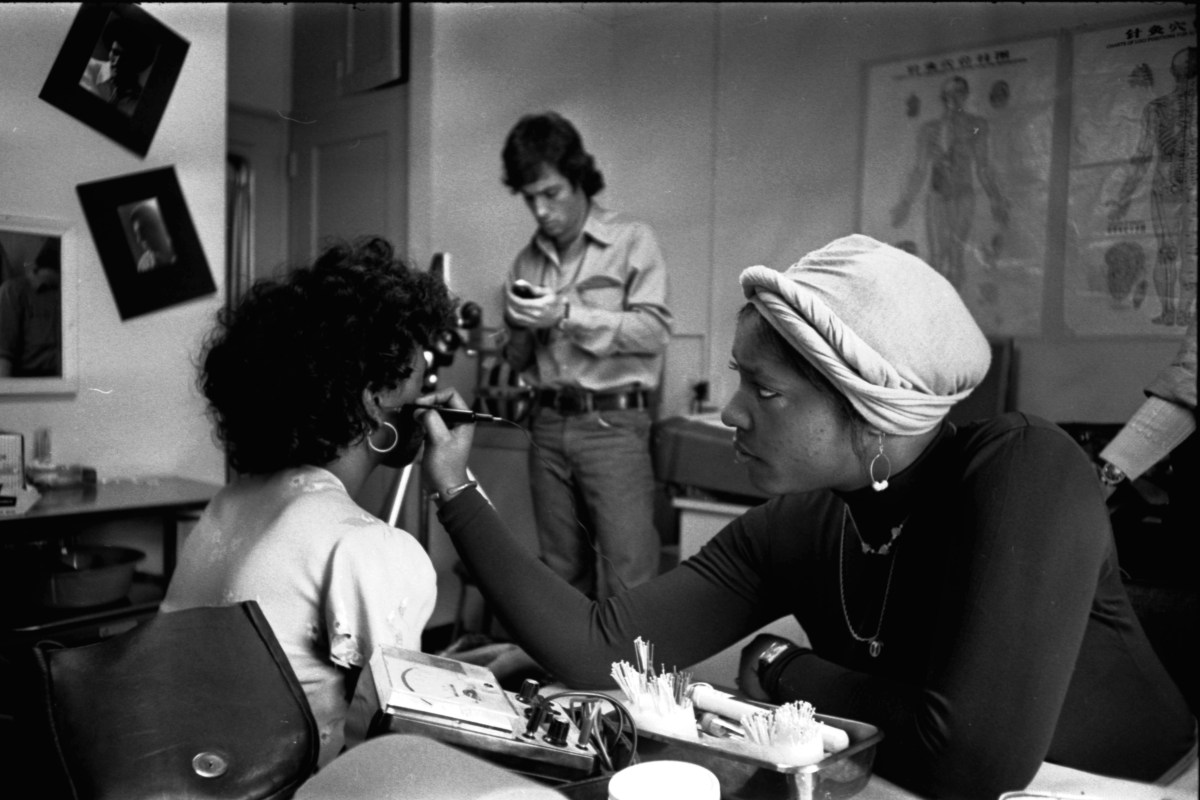

Shakur became interested in acupuncture after learning about its use as a widely dispensed community health service in Maoist China. He wondered if it could be used to treat heroin withdrawal and invited Dr. Mario Wexu, a Montreal-based acupuncturist, to the South Bronx. Dr. Wexu trained members of the Young Lords and Black Panthers on how to administer a five-point, ear-based acupuncture protocol. The program was a massive success. Patients were able to get off heroin and methadone. As they got clean, they brought other users to the clinic. Many former patients started volunteering and receiving acupuncture training.

Lincoln Detox became much more than a detox clinic. Shakur, the stepfather of the late rapper Tupac Shakur, helped it become a trusted center of community health. Treating heroin withdrawal was an instrumental first step, but there were deeper, more systemic afflictions to address. Shakur created new programs to mobilize and educate the community. The P.E. classes that the Black Panthers started offering at Lincoln did not stand for “phys ed.”

“They were political education classes,” Donovan says, “and they provided a lens to see who drugs really served in society and how they were part of a chemical warfare. They emphasized that communities had to work together to resist drugs, because the drugs were flooding into communities after the civil rights movement and were being used to pacify their mobilization.”

Dope is Death documents the potent efficacy of this work and the consequences of its success. As Shakur’s programs and following grew, he was targeted by Hoover’s FBI. COINTELPRO, the Bureau’s clandestine and illegal domestic surveillance apparatus, had been used since 1956 to monitor, harass and persecute political adversaries.

“Communism was the original threat COINTELPRO addressed,” Donovan says. “And then it seemed like its mission was to prevent the rise of a ‘Black messiah.’ It was like total white supremacy. And the idea of surveilling these groups and individuals was basically, ‘Let’s keep an eye on potential black leaders who could really rise and unite their communities.’ Like Martin Luther King Jr. Like Fred Hampton. Like Mutulu Shakur.”

On October 20, 1981, an armored Brink’s truck was robbed near Nyack, New York. One Brink’s guard and two Nyack police officers were killed. Although no evidence linked Mutulu Shakur to the crime, the FBI alleged that he was the mastermind. After four years on the run, Shakur was arrested and charged through the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO), a statute that was designed to prosecute leaders of organized crime. The criminal enterprise the FBI accused Shakur of running was BAAANA, the Black Acupuncture Advisory Association of North America. After a lengthy trial that included a number of human rights violations, he was convicted in 1988 and sentenced to 60 years in prison with the recommendation for no parole.

Shakur, who eventually became a doctor of acupuncture, is the main character in Donovan’s film even though she wasn’t allowed to interview him on camera. His story is a jarring reality check for anyone who thinks America doesn’t have political prisoners. It also underscores the inhumanity of mass incarceration, a distinctly racist and American phenomenon. Shakur has been imprisoned for more than 30 years. In 2019, he was diagnosed with terminal bone marrow cancer. He’s had COVID twice and been denied parole nine times, including on the grounds of a compassionate release.

“By the FBI’s own numbers, individuals over 70 have a 0% recidivism rate,” Donovan says. “He’s not a threat to society.”

Shakur’s legal team posts regular updates on his website. Donovan communicates with him frequently and says incarceration has not blunted his community-first ethos or his proclivity for leadership.

“He’s still doing a lot of work inside prison in terms of organizing people,” she says. “He runs what he calls ‘empathy classes’ for rival gang members. In terms of acupuncture, he can’t have needles, so he teaches breathing exercises. He’s just such a powerful force.”

For such a tightly focused project, Dope is Death covers a lot of terrain. The 80-minute film weaves together a number of threads, each one worthy of its own documentary. And similar to Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah, it offers a compelling counter-narrative to official accounts of recent history. We need more stories like these — that challenge hegemonic myths — if we’re serious about making the present different from our troubled past.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.