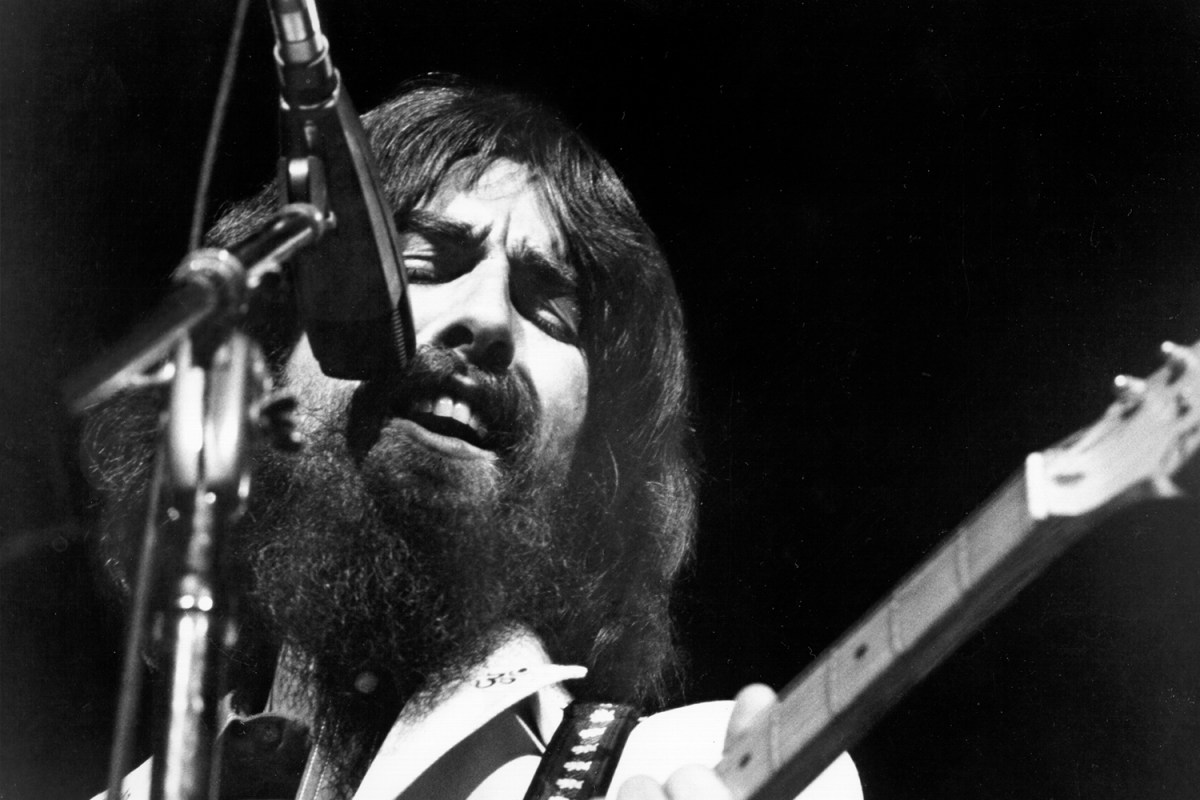

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who identify George Harrison as their favorite Beatle, and those who haven’t learned enough about him to reach that logical conclusion. The Concert for Bangladesh, which celebrates its 50th anniversary on August 1st, gives us a timely opportunity to make the case.

On July 27, 1971, Harrison held a press conference in a cramped, smoke-filled Broadway office. He was flanked by Allen Klein, his shrewd yet unscrupulous business manager, and his good friend Ravi Shankar, the virtuoso sitarist with whom he was hosting a special concert at Madison Square Garden the following Sunday.

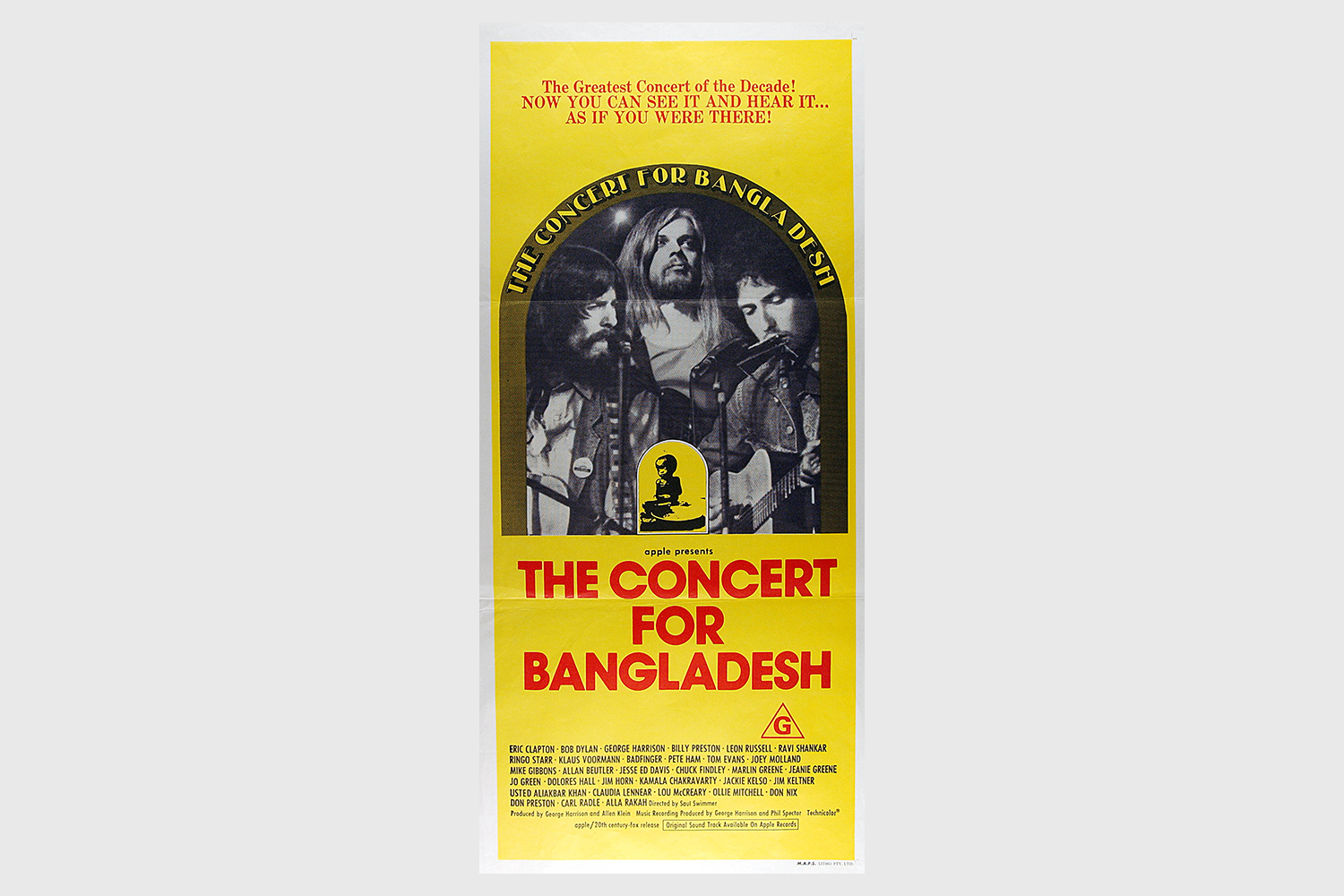

There had never been anything like it. A flock of unidentified rockstars, cloaked under the mysterious billing “George Harrison and Friends,” had agreed to donate their time, talent and future earnings to support a pressing cause. All of the box-office proceeds, plus the substantially more lucrative sales from a concert album and film, would go directly to aiding refugees in war-torn Bangladesh.

Media interest swirled as the concert drew near. The ink on The Beatles’ divorce papers was still wet, so naturally the reporters at the press conference were eager to probe the recent past. After a few Beatles questions, Harrison intervened.

“Let’s talk about the concert really. The concert is here. I mean the whole idea of it is to try to help some people and we are not really here to talk about The Beatles.” He held up a photograph of a gaunt, famished child and said his final piece on his former band. “It’s not incidental that The Beatles should be mentioned, but it’s not really the purpose of being here.”

His resolve and maturity belied his youth. He was only 28, but he was an old soul. (One of the more absurd and taken-for-granted elements of The Beatles’ story is that they were all under 30 when they broke up.) The reporters, duly heeled, turned to Bangladesh.

The phrase “raising awareness” has become something of a cliché in the world of celebrity philanthropy, but Harrison’s comments literally put Bangladesh on the map for millions of people.

“Bangladesh suddenly became a tangible entity, culturally and intellectually if not yet in physical reality,” Graeme Thompson wrote for GQ earlier this year. “Every press article about the concert had to give at least a thumbnail sketch of what was happening in eastern Bengal.”

Underpinning Harrison’s commitment to the cause was a deeply personal connection.

“With all of the enormous problems in the world,” a journalist asked, “how did you happen to choose this one to do something about?”

“Because I was asked by a friend if I’d help,” Harrison replied, his voice and eyes emitting primal empathy. “That’s all.”

Born to a Bengali father and raised in northern India, Shankar was deeply distressed by the humanitarian crisis underlying Bangladesh’s War of Independence. After the British Partition of India in 1947, Bangladesh became East Pakistan and was put under the control of West Pakistan. They were separated by a thousand miles of Indian subcontinent. Geographically and culturally, the conjunction made little sense.

Social, political and economic conflicts flared from the beginning. In late 1970, a devastating cyclone killed 500,000 people in East Pakistan. The central government in West Pakistan provided slow and underwhelming relief. Their cruelly indifferent response galvanized a growing liberation movement. On March 26, 1971, Bangladesh declared its independence. War broke out before the end of the day.

It was a gruesome guerilla war. Both sides committed atrocities, but the magnitude of the crimes perpetrated by the Pakistani Army was far greater. They used the war as a pretense to mount a genocidal campaign against dissidents, intellectuals and Hindus. Estimates vary widely, but anywhere from 300,000 to 3,000,000 people were murdered and dumped in mass graves. Heightening the terror was the prevalence of state-sanctioned rape. Pakistani soldiers assaulted between 200,000 and 400,000 Bengali women and girls, often enslaving them in military brothels. Of the 10 million refugees who fled to India that spring, many were orphans. Disease and famine, exacerbated by the ongoing effects of the Bhola cyclone, made their plight even more dire.

The Western world was slow to acknowledge the crisis, partly because the foreign press corps had been systematically expelled from Bangladesh before the war. That changed on June 13, 1971 when Anthony Mascarenhas, a Pakistani journalist, published a stomach-twisting account of atrocities he witnessed while embedded with the Pakistani Army. Starkly titled “Genocide,” it ran in London’s Sunday Times and made the situation impossible to ignore. The international community, however, was reluctant to intervene — Cold War politics played a nefarious role — and the suffering continued.

Ravi Shankar was in Los Angeles at the time and followed the news with despair. He wanted to make a direct impact and came up with the idea of playing a concert to raise money. He didn’t expect to raise much, maybe $25,000, but at least it was something. When Harrison flew to L.A. that June to work on the soundtrack for Raga, Howard Worth’s documentary about Shankar, the sitarist asked his friend for help. Maybe if Harrison made an announcement or endorsed the concert, Shankar suggested, that would create enough buzz to hit the fundraising goal.

“If you want me to be involved,” Harrison told Shankar, “I think I’d better be really involved.”

Shankar gratefully accepted the offer, and Harrison put all of his other projects on hold to help organize the benefit concert. He quickly formed a production team, enlisting Allen Klein to handle negotiations with record labels and bringing in Phil Spector to produce a live album. After consulting with an Indian astrologer, they settled on early August as the ideal date. Harrison wanted to go big, and no venue was bigger than Madison Square Garden, so he booked it for August 1. That gave the team less than five weeks to prepare.

Harrison’s next order of business was contacting his musician friends. He quickly got commitments from Leon Russell, Klaus Voorman and Ringo Starr. (He made overtures to the other Beatles. Paul McCartney still had a sour taste in his mouth from the breakup and declined; John Lennon initially accepted but pulled out when Harrison intimated that the invitation did not extend to Yoko Ono.) Badfinger, the Welsh rock band, signed on along with Billy Preston, the prolific session keyboardist and Grammy-winning solo artist. This was a solid nucleus, but Harrison hoped to land two more big names to elevate the concert’s stature.

Eric Clapton was not doing well when Harrison rang. For over a year he had been living in self-imposed exile. He was in a dark depression — driven partly by his infatuation with Harrison’s then-wife, Pattie — and was snorting ungodly amounts of heroin every day. Clapton told his friend that he couldn’t make the concert. Harrison was persistent.

“He was only too aware of my drug problems and may have seen this as some kind of rescue mission,” Clapton wrote in his autobiography. “Whatever the reason, I told him I could go only if he could guarantee that they could keep me supplied.”

Wading into murky waters, Harrison agreed. Clapton’s presence would be a huge boon to the lineup and album. That left one final star for Harrison to chase.

Bob Dylan hadn’t performed in front of an audience in two years. He had barely made any public appearances since a mysterious motorcycle accident in 1966, so it wasn’t likely that he would come out of seclusion to perform on the world’s biggest stage. But he was immensely popular, and Harrison knew he would inject the show with rocket fuel. To his surprise, Dylan said yes. Perhaps pushing his luck, Harrison made one request: that Dylan include “Blowin’ in the Wind” in his set.

Rankled that Harrison was dredging up a song he had tried to move on from, Dylan allegedly fired back, “Are you gonna sing ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand’?”

With the lineup secure but the individual performers kept a secret from the public — for suspense but also to hedge against eleventh-hour defections — Harrison set about promoting the event. The afternoon show sold out immediately, so they decided to add an evening performance. On top of all the logistical and business work, Harrison wrote and recorded a single, “Bangla Desh,” which came out the week before the concert and soared up the charts.

The breakneck speed of the preparations kept Harrison from dwelling on the pressure of his own role. Soft-spoken and self-effacing, he was a reluctant frontman. At a July 27 press conference, a reporter asked how he felt about being the sole headliner of such a massive endeavor.

“Nervous,” he replied. “I prefer to be part of a band, but for this it was just something we had to do in order to get the money. We had to do it quick, so I had to put myself out there and hope I’d get a few friends to come and support me.”

Some of these friends didn’t help alleviate stress as the concert approached. After missing several flights, Clapton finally arrived. He looked like death. There was heroin waiting in his hotel room, as promised, but there was a problem.

“It turned out that what they had scored for me was street-cut,” Clapton wrote, “so that it was about a tenth as strong as what I was used to. The result was that I went cold turkey for the first two or three days and missed all the rehearsals. I just lay on the bed in our hotel room, shaking and mumbling like a madman.”

As Clapton endure his own Trainspotting nightmare, Harrison dealt with another problem. Dylan was getting cold feet. After missing several rehearsals, he showed up at Madison Square Garden the night before the concert. He stood on the stage with Harrison and beheld the legendary venue.

“It suddenly was a whole frightening scenario,” Harrison later remembered. “Bob turned to me and said, ‘Hey man, I don’t think I can make this. I’ve got a lot of things to do in New Jersey.’”

Harrison balked. “Look, don’t tell me about that,” he said.

He proceeded to give his friend a stern pump-up speech, but when he woke the next morning he wasn’t sure if Dylan would show. Regardless, the concert was happening. After a quiet breakfast at the Park Lane Hotel, Harrison and his entourage headed to the Garden.

A little after 2:30 p.m. he walked onto the stage. The thunderous adulation of 20,000 fans made him visibly uncomfortable. When it finally died down, he assumed the role of a genial host. He thanked everyone for coming and introduced the first act.

“We’ve got a good show lined up. I hope so anyway. First part of the concert is gonna be an Indian music section. You’re gonna hear a sitar and sarod duet. And as you realize, Indian music’s a little bit more serious than our music, and I appreciate if you could try and settle down and get into the Indian music section.”

Opening with a 45-minute performance from Shankar was a strong gesture. It placed Indian music and culture at the center of the show. Shankar was joined by two world-class musicians, Ali Akbar Khan on sarod and Alla Rakha on tabla, a kind of hand drum. Their set was a watershed moment in exposing Western ears to Eastern sounds, something Harrison had been striving to do since he played sitar on “Norwegian Wood.” But the crowd, to be candid, was somewhat restless. They cheered awkwardly when Shankar and Khan tuned their instruments.

“I hope you like the music as much as you liked the tuning,” Shankar cracked.

Despite the sublime performance that followed, Don Heckman wrote in his coverage for The Village Voice, “the audience attitude was more one of toleration than interest.” After an intermission that featured graphic footage from Bangladesh, Harrison led his all-star band onto the stage. He had changed his outfit since the introduction. He wore a well-cut white suit with white shoes, his shoulder-length hair framing his solemn face. He exuded strong messianic vibes.

The band’s eight-song set was a triumphant declaration of rock and roll’s endurance. The ’60s might be over, but the music had no intention of fading quietly into the night. Harrison opened with two energetic originals, “Wah-Wah” followed by his chart-topping “My Sweet Lord,” before handing the reins to his friends. Billy Preston had the Garden pulsing with “That’s the Way God Planned It,” and then Ringo blew the roof off with a spirited rendition of his new song “It Don’t Come Easy.” Leon Russell marched the troops through a high-octane medley of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and “Young Blood,” but two Harrison-penned Beatles songs stole the set.

“While My Guitar Gently Weeps” drew raucous applause as the audience seized its chance to honor a guitar god. Clapton had been given methadone and somehow made it out of his hotel. Although he sounds fine on the concert’s album, he looked like hell. To his credit, he didn’t scrub the narrative in his autobiography.

“At the last minute I got to the sound check and quickly ran through some of the things I was supposed to do, and although I have a vague memory of this, and then of playing the show, the truth is I wasn’t really there.”

After closing the set with “Here Comes the Sun,” it was time for Harrison to introduce the next act. He wasn’t sure what would happen, or if the artist was even in the building, but he took a deep breath and addressed the crowd.

“Like to bring on a friend of us all,” he said. “Mr. Bob Dylan.”

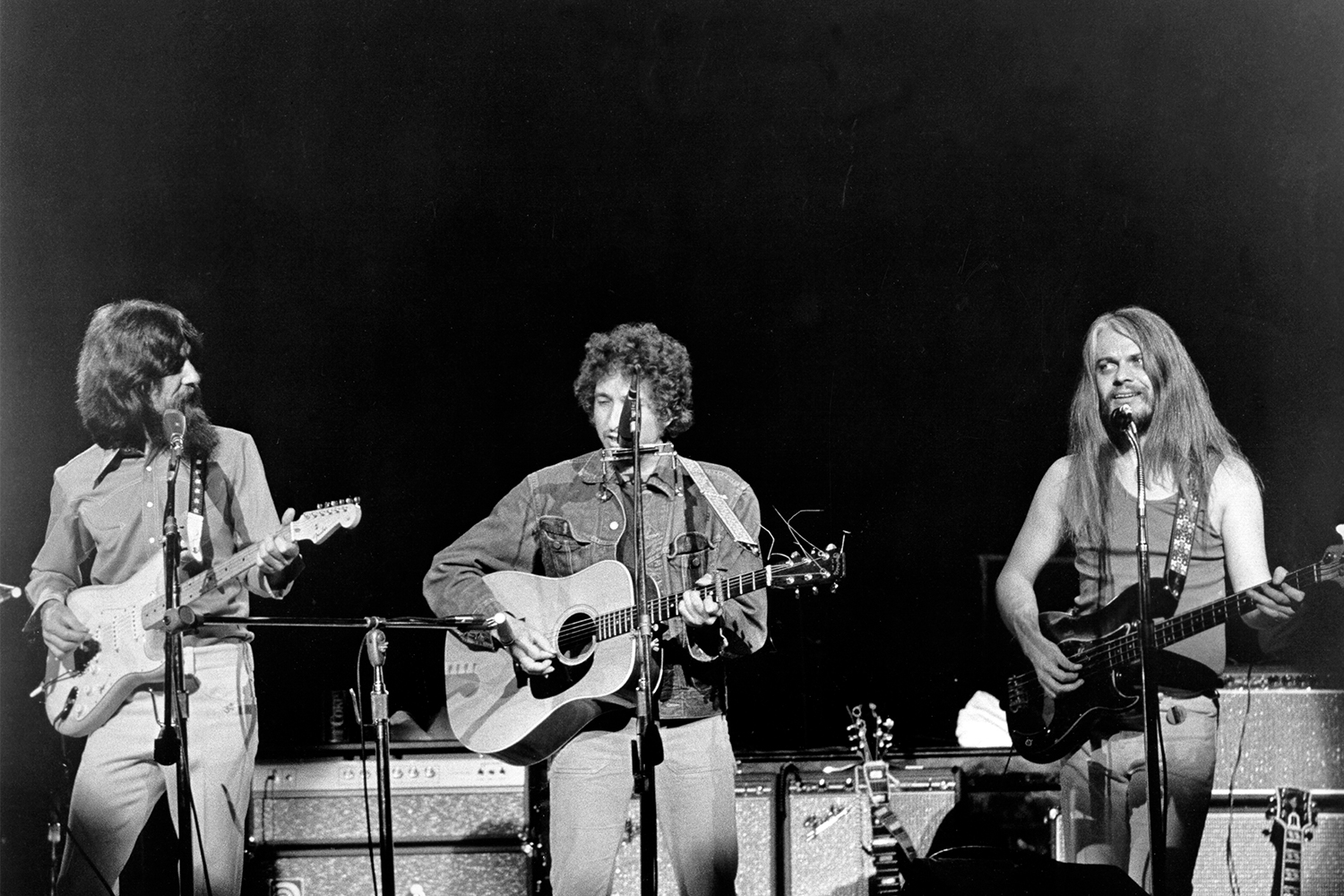

Before Harrison could even turn around, Dylan materialized on stage. Sporting a denim jacket and a scruffy beard, he looked hale, much healthier than his amphetamine-fueled beatnik days. As the audience lost its collective shit — nobody had any idea Dylan was a possibility — he hastily adjusted his microphone and launched into “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” His five-song set, accompanied by a light brigade of Harrison, Starr and Russell, was “the real cortex-snapping moment” of the show, according to Heckman.

The concert ended with “Something,” Harrison’s effervescent love song, and a rousing encore of “Bangla Desh.” When the musicians returned to the hotel to pass the time before the evening show, Harrison and Dylan were jubilant. Jacked up on adrenaline, they rehashed the performance and tweaked the setlist.

By all accounts, the evening show was even more successful. Harrison gave himself the night to celebrate with everyone at Ungagno’s, a Manhattan nightclub, but the next morning he was in the studio working on the concert’s album. He hoped to release it within 10 days in order to get the money to Bangladesh as quickly as possible, but his optimism was thwarted by myriad headwinds.

For starters, the quality of the concert’s audio recordings was less than optimal. Harrison and Spector pursued the laborious task of stitching together clips from the afternoon and evening shows. Throughout this process, Spector was in and out of the hospital with various alcohol-related illnesses, so the burden fell on Harrison’s shoulders. He bore it without complaint and finished the three-disc album by the end of August. Unfortunately, a nasty dispute with Capitol Records threatened the release.

Capitol had a distribution deal with Apple, The Beatles’ record company that paid for the album’s production, and Harrison expected them to distribute the album at cost. When Capitol’s chairman Bhaskar Menon demanded more money, Harrison was livid. Refusing to budge, he aired his grievances during a November 23 appearance on The Dick Cavett Show.

“This record should’ve been out a month ago really. But now we still haven’t solved the problem. We’ve got Dylan. Dylan is at CBS [Records] and they’re cool about it …We’ll get it out. I mean, I’ll just put it out with CBS and let Bhaskar sue me.” He pumped his fist and flashed a wily grin at the camera. “We’re gonna play the sue me, sue you blues!”

(The entire Cavett interview is excellent. It’s an hour of Harrison’s self-deprecating wit loaded with thoughtful takes and colorful anecdotes.)

Harrison eventually prevailed. Capitol backed down and the album hit stores in late December. Critically and commercially, it was a massive success. It won the Grammy for Album of the Year and sold millions of copies. The film premiered the following spring, generating even more awareness and money. After one last hurdle, a frustrating dispute with the IRS — they refused to acknowledge the concert’s tax-exempt status because Harrison hadn’t formally partnered with a charitable organization at the start of the planning process — Harrison and Shankar were finally able to release the funds.

Part of the reason they hadn’t designated a partner sooner is because they received bad guidance from Klein, a licensed accountant who later spent time in jail for tax evasion, but it was also because they were flying blind. There was no blueprint for this kind of event, and they didn’t know what they didn’t know. Once it became clear that they needed to team up with a trustworthy non-profit to ensure the money reached where it was needed most, they conducted an extensive search process.

After personally interviewing representatives from different organizations, Harrison and Shankar ultimately selected UNICEF. The agency had already been on the ground in Bangladesh for 20 years and had a history of partnering with public figures such as Danny Kaye and Audrey Hepburn to support the world’s children.

“The Concert for Bangladesh built on that tradition and created a new blueprint for the power of music to support impact,” Michael J. Nyenhuis, President and CEO of UNICEF USA, tells InsideHook.

It’s not hyperbolic to say that the concert, conceived out of love and despair during five frantic weeks in 1971, changed the world. Not only through the millions of dollars of relief it raised for Bangladesh, but through its sweeping influence.

“George and Ravi’s idea paved the way for others to follow and inspired countless global citizens,” Nyenhuis says. Charity concerts like Live Aid and Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival, which benefits the drug treatment center Clapton founded in Antigua, descend directly from the Concert for Bangladesh.

“George’s legacy as a music icon,” Nyenhuis says, “is matched by his philanthropic spirit.”

To honor that legacy, Olivia Harrison, George’s widow, partnered with UNICEF USA to create the George Harrison Fund in 2005. While forever linked to Bangladesh, the fund has expanded to aid children all over the world. To date, it has raised over $17 million to support UNICEF.

It’s hard to believe that half a century has passed since the quiet Beatle hosted a rock concert. He had no idea it would leave the kind of cultural and philanthropic footprint it did, but he wasn’t worried about that. He just wanted to help a friend.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.