“Look at the history of the art world and it’s been wrong so many times in its judgment of what constitutes art. ‘This guy isn’t an artist. You’ll never see a Basquiat in a museum. It’s disgusting,’” laughs Thierry Guetta. “And in the end of course it’s a $100 million painting that is in a museum. Duchamp, Picasso — it was the same for them. Van Gogh never sold a painting in his lifetime.”

Guetta — better known as the street-cum-pop artist Mr. Brainwash — could almost have been talking about his own career, were it not not for being discovered by, well, the bigger street-cum-pop artist Banksy, and then featured in the latter’s 2010 Oscar-nominated documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop. Instead, Guetta has had a very different experience to Vincent.

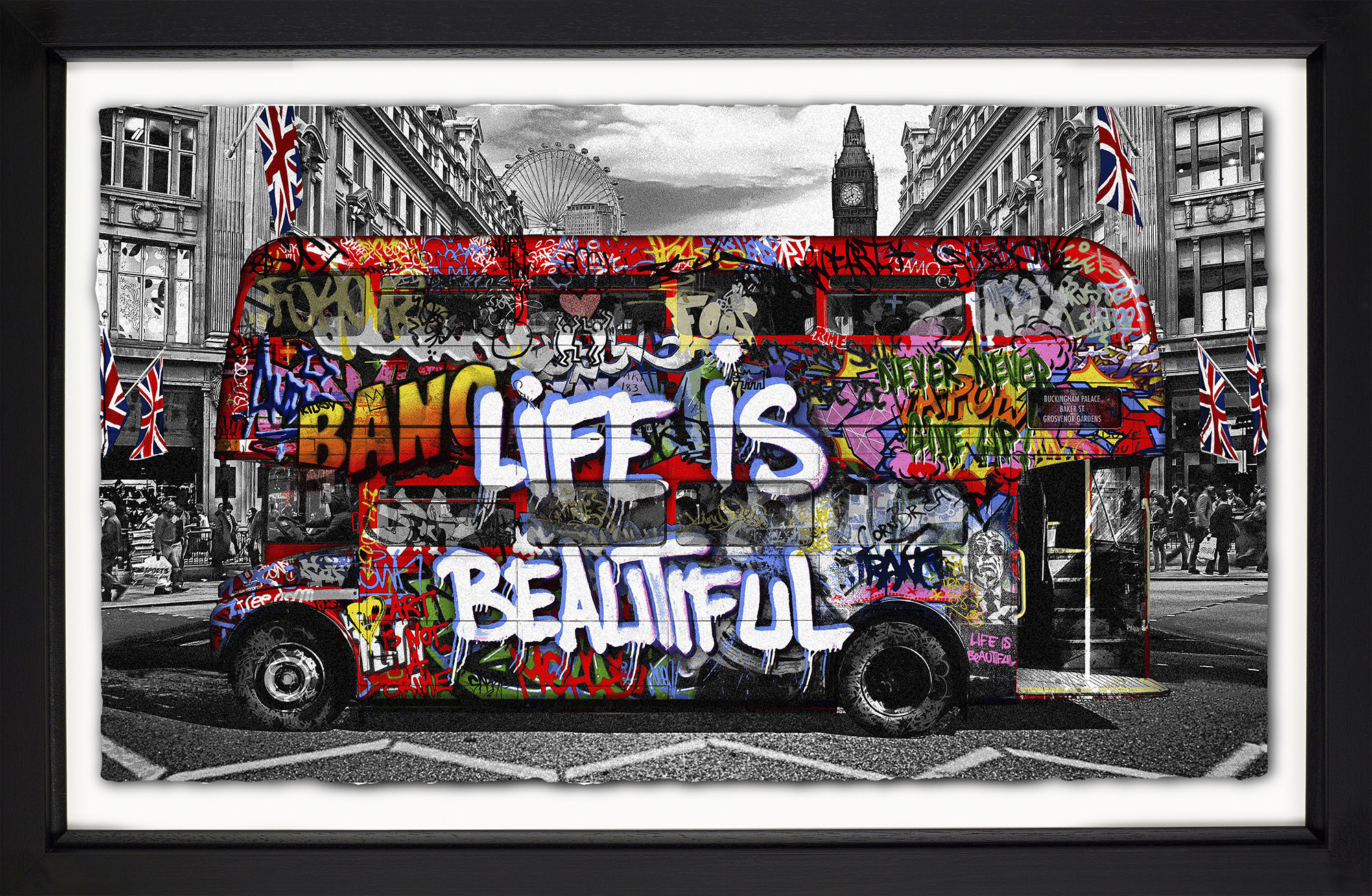

His fun, referential works have — in a decade — made him millions, seen him work with Mercedes and Nike, design the centenary Times Square hoarding for Coca-Cola, and album covers for Red Hot Chili Peppers, Michael Jackson and Madonna. He’s collaborated on charity projects with Michelle Obama and the Pope. And by the end of the year he’ll have opened not just a gallery, but, he says, a museum of his work in a Richard Meier-designed building on Beverly Drive in L.A., the city the Frenchman calls home. No wonder his cheesy, oft-repeated yet apparently sincere mantra is “life is beautiful.”

As for whether he ever ponders what would have come of his art if he and Banksy had never crossed paths, he’s philosophical, in characteristically fortune-cookie style. “I think that whatever you were supposed to be or supposed to do will come to you. I don’t think there are any ifs in life,” he says. “Whatever happens is supposed to happen, so my life has turned out the way it is not because something has happened but because it’s a continuation of whatever my life is.”

If, indeed, it is his life. One of the weirder things about the career of Mr. Brainwash is the dogged accusation that, in fact, he is Banksy, or at least a creation of Banksy. It’s the fedora and the moustache, the heavy accent and, well, that moniker, with the oh-so-subtle subtext that it all may just be some kind of joke.

“Well, when you say ‘you are [Banksy],’ they say, ‘no you’re not.’ And when you say, ‘I’m not,’ they say. ‘Yeah, sure you are.’ So, you know what, fuck it,” laughs Guetta. “They can find out when all is revealed. In life everything comes out in the end. Now is not the right time, but time will tell. And it will be a big surprise. I’m not being cryptic …”

Although, of course, he is. What he will say is that said museum will unveil a whole new side to his artistry. His work may be best known for being smiley and positive, much like the artist himself, with its nods to Warhol, the Impressionists and, funnily enough, Banksy, to the point that he’s been accused of, shall we say, a lack of originality. Again, it’s another claim he shrugs off.

“When I take influence from other artists’ work, for me it’s more like an homage. It’s something good. For sure these are artists that I admire and love. And it’s not as though you don’t know it’s my work,” says Guetta. “I’m more a pop artist than anything else — pop as in popular. Because I want art to have an influence on people. That’s the way it should be, without the labels, though the art world is always trying to give it labels. It’s just art that speaks to some people and doesn’t speak to other people.”

But what’s coming, he says, will be a whole lot darker — or, at least, as dark as someone so relentlessly positive can be, “with a hint of light in it, that shows you what life could be,” he says. And it’s been a long time coming. “I’m 55 and I’ve been very patient,” he chuckles.

“Let’s say that I’ve worked for 15 years showing work that was happy, that was colorful, that I hoped made people happy, and the more I did that the more people wanted it. But I haven’t yet shown any of the kind of work that I wanted to, so much as the work I felt people wanted to see,” says Guetta, explaining his money trap.

“On the side of that work I was doing something that expressed another part of me, artistically, and which I felt I couldn’t show [because that would have hindered the building of my career at the time],” he adds. “And that other side of myself is an aesthetic that’s very different to what I’m known for, such that I’ve been judged on something that doesn’t represent all of who I am.”

Not that Mr. Brainwash can’t be entirely candid. That name, for example, he says is a comment both on the state of culture — “Really we’re all brainwashed, right? Every one of us — the shoes you wear, the food you eat, the TV you watch … we’re in a world of brainwashing.” — and, confessionally, his part in it. “I’m someone who wants to brainwash in a good way,” he adds, “to bring you something that makes you feel good.”

Likewise his thoughts on art world, which he says is all just a game — played invariably by people who don’t know it’s a game — in which artistic credibility is besides the point. “I think everything is good [about the art system] if there’s someone who wants to spend $100 million on a painting. And a few years from now it will be $200 million,” he chuckles, not quite being clear on whether he’s serious or cynical. “Street art is going through the same process that pop art went through during the 1970s, when that came out of the corner and people really didn’t know what to do with it at the time, though little by little collectors started to buy into it. Street art is today’s pop art and will go the same way, moving towards ever greater acceptance.”

“But that says more about the fact that money today isn’t what it was before,” he adds. “People become billionaires overnight now because they’ve designed an app. So [how art is valued] suddenly has no rules. Who knows where this art market is going. The only thing that’s clear is that it isn’t going away.”

Nor, no doubt, will his sales: he — and the art market — appear to be in perfect confluence, his accessible, cheery, not-too-challenging works perfect for loft walls and poster reproduction, edgy enough to get progressive collectors interested, not so edgy that they hinder his commercial employment on the side. That’s more millions to him.

“But I really don’t think that money has changed me because I feel rich on the inside and I know you can’t buy that,” he says, in a way that sounds utterly believable. “Money physically, well that comes and goes. Sure, it’s better to have it than not but if you said ‘I’ll give you all the money in the world but take the richness you feel inside of you,’ well, that’s deal I wouldn’t accept.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook LA newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Southland.