Before he stood tall as the Commander in Chief, John F. Kennedy first demonstrated the mettle he would carry with him into the presidency on a moonless August night while he was serving in the United States Navy during World War II.

Seventy-five years ago today, Lieutenant Kennedy and 12 other crew members set out aboard a Patrol Torpedo (PT) boat into the Blackett Strait in the Solomon Islands under a starless sky. PT-109’s mission, along with the 14 other PTs that accompanied her, was to intercept Japanese ships.

Despite the darkness, the convoy of PT vessels encountered a quartet of Japanese destroyers and attempted to engage them. Torpedoes were fired but neither side scored a hit – at first. As U.S. vessels that were out of ammo departed the fray, three remained behind. One of those was PT-109.

While Lt. Kennedy and his crew were searching for a target in the blackness, one of the destroyers – later identified as the Amagiri – emerged out of the dark and struck PT-109 near its starboard torpedo tube, effectively chopping the boat into two.

Two crew members were killed instantly. The destruction of the boat was so massive the two remaining PT boats in the area assumed all 13 seamen had died. They left the area without checking for survivors.

Had it not been for Lt. Kennedy, one of those survivors, engineer Patrick McMahon, would have joined his dead crew members in Davy Jones’ Locker.

Badly burned on his face and hands by exploding fuel during the impact, McMahon ended up lost in the water along with a number of other members of PT-109’s crew. Lost, but not forgotten as Lt. Kennedy – who sustained a debilitating back injury of his own thanks to the Amagiri – was able to locate McMahon and haul him back to the remains of the boat and the rest of the men.

At sunrise, the 11 survivors set out swimming for an island located 3.5 miles away with Lt. Kennedy clutching a belt tied to McMahon’s life jacket between his teeth to tow the injured sailor.

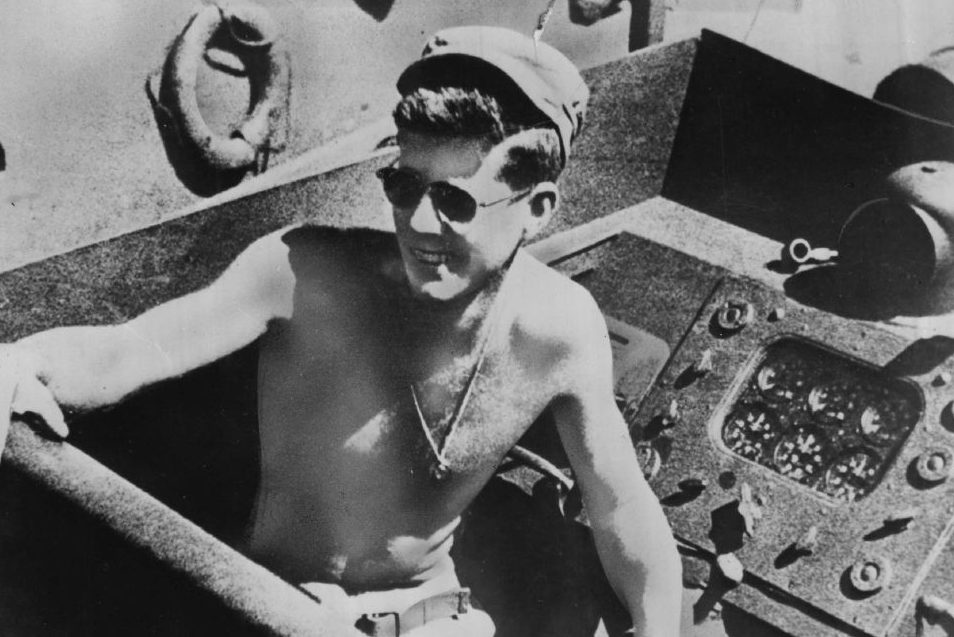

John F. Kennedy and the crewmen of the PT-109. Back Row (L-R) Allan Webb, Leon Drawdy, Edgar Mauer, Edmund Drewitch, John Maguire, Lt. (jg) John F. Kennedy (standing, far right). Front Row (L-R) Charles Harris, Maurice Kowal, Andrew Kirksey, and Lenny Thom. The Solomon Islands. (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

Despite hauling McMahon, Kennedy was the first to reach land on the island of Plum Pudding, but the former Harvard swim team member was not done in the drink. After days of resting and fruitlessly looking for rescue from passing PT boats, Kennedy led the men back into the ocean on August 4 to head to a new island that would have food and water and be closer to the Ferguson Passage.

Leaving most of the crew on one island, Lt. Kennedy and another crew member reached a neighboring one on August 5. There they found the wreck of a Japanese vessel and two natives investigating it. Spooked by the sailors, the islanders paddled away in a canoe — despite Kennedy’s protests.

Upon returning to the crew, Lt. Kennedy encountered the same islanders and discovered they were actually scouts for the Allies who had stopped at the island to gather coconuts.

That discovery was key as the men showed Lt. Kennedy how to carve a message into the shell of a coconut and offered to deliver it. Brought to a nearby naval post, the lieutenant’s coconut read: “NAURO ISL…COMMANDER…NATIVE KNOWS POS’IT…HE CAN PILOT…11 ALIVE…NEED SMALL BOAT…KENNEDY.”

Replica of PT 109 and part of the crew that served on it w. John F. Kennedy during WWII taking part in the Inaugural parade. (Photo by Yale Joel/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)Once the message was delivered, eight islanders returned with food and instructions for Lt. Kennedy to come with them through the enemy-held waters while smuggled under a pile of palm fronds to Gomu Island to meet with the local Allied coastwatcher and plan a rescue.

Lt. Kennedy went and insisted on going back with the rescue PT boats that returned to pick up PT-109’s survivors so he could guide them through the foreign waters.

After all was said and done, the 11 men who had survived what had befallen PT-109 on August 1 arrived safely at the U.S. base at Rendova at 5:30 a.m. on August 8.

When he returned home, Lt. Kennedy was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his leadership and courage. Thanks to the injuries he suffered, he also qualified for a Purple Heart.

To commemorate all that had happened, the message-delivering coconut was made into a paperweight that JFK kept on his desk throughout his career in politics (including in the Oval Office) and it is now on display at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Considering how much the experience meant to him, Kennedy keeping the coconut close to him is far from bananas.

“JFK’s military service – the sinking of PT-109 and especially the loss of two of his crew – was a transformative experience in his life,” JFK Library curator Stacey Bredhoff told RealClearLife. “He emerged from the experience a decorated war hero with battle-hardened views of war and peace that he would later carry into his presidency.”

The coconut shell encased in wood and plastic which JFK used as a paperweight on his desk in the Oval Office. (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

To learn more (or at least a dramatized version of more) about this miraculous story, check out 1963’s PT-109, a film starring Clift Robertson as Kennedy.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.