On July 1, 1992, A League Of Their Own graced movie screens for the first time.

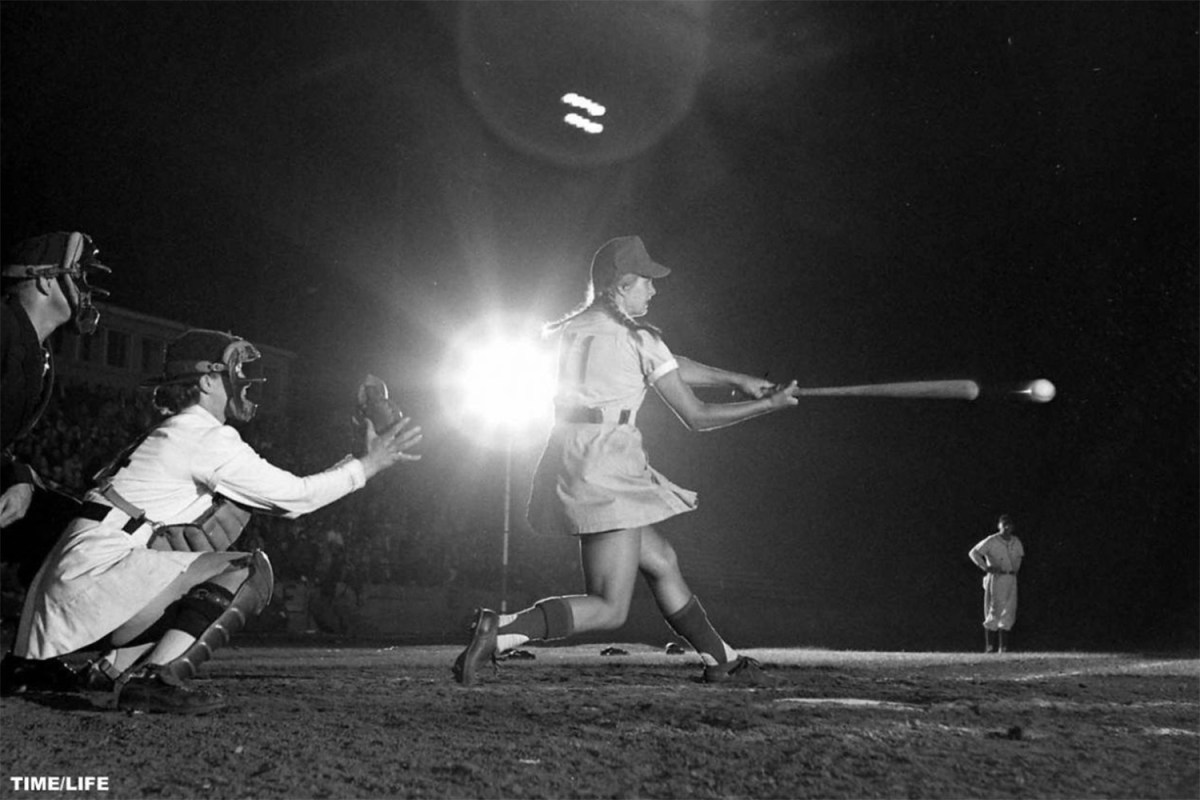

Directed by Penny Marshall and starring Geena Davis, Lori Petty, Tom Hanks and Madonna, the classic sports film was one of the first to feature female sports protagonists. It’s a fictionalized account of the real-life All-American Girls Playing Baseball League (AAGPBL), which cropped up as World War II depleted the benches of the MLB.

In the film, we follow Dottie Hinson and Kit Keller, two baseball-loving sisters — a catcher and pitcher, respectively — who get recruited to the nascent league. Between sparring with each other and their has-been manager Jimmy Dugan, their team, the Rockford Peaches, attempts to win the league championship. It’s full of heart, laughs and excellent baseball action.

In the 30 years since its original release, the film has been added to countless lists of best sports movies of all time (#10 according to Men’s Health, #22 for both Bleacher Report and ESPN), and in 2012 it was selected to the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, due to its cultural and historical significance.

You definitely know the film’s most famous line, #54 on AFI’s 100 Greatest Movie Quotes Of All Time: “There’s no crying in baseball.”

The film was a commercial, critical and cultural success. BoxOfficeMojo calculates it as the number-one selling baseball movie of all time — it grossed over $132 million worldwide on a $40 million budget.

In honor of the film’s 30th anniversary, we look back on the true story of the AAGPBL and celebrate another of Chicago’s great inventions. If, by the end, you’re itching for more dirt in the skirt, fear not: A new chapter for the AAGPBL arrives this August, as Broad City’s Abbi Jacobson heads up a one-hour Amazon Prime TV series called, you guessed it, A League of Their Own, co-starring D’Arcy Carden (Janet on The Good Place) and Nick Offerman (Ron Swanson on Parks & Recreation).

Chicago Gum-Slinger Philip K. Wrigley Founded the League

The film sort of disguises this fact — and depending on when you last saw it, you might not realize the fictional league founder and candy king “Walter Harvey” is none other than Philip K. Wrigley.

In real life, Wrigley, who had inherited the Chicago Cubs from his father, was notified by the War Department that due to World War II efforts, the MLB would have to suspend play so the men could go serve. Fearing the financial implications of major and minor league stadiums sitting unused, Wrigley asked his staff to brainstorm alternative uses for his ballparks.

They came up with the idea of establishing a women’s league to use Midwestern stadiums, attract some crowds, and basically keep the lights on. His principal advertising executive, Arthur Meyerhoff, the Chicago Cubs’ lawyer and the Cubs’ chief scout were charged with establishing a preliminary plan for league operations, and other members of the Cubs’ staff were assigned to operate the league for its inaugural season in 1943.

The AAGPBL fielded four teams that first year: Racine Belles, Kenosha Comets, South Bend Blue Sox and, of course, the Rockford Peaches. Wrigley invested $22,500 for each team and found team guarantors in each franchise city — businessmen who would contribute an additional $22,500 to sponsor a team.

The league ran from 1943 to 1954. Its motto: Do or die! (Eat your heart out, MLB.) By the end of its run, over 600 women had become professional athletes, paid to play baseball.

Wrigley isn’t the ultimate hero here, however. As addressed in the film, when it became clear WWII wouldn’t stymie the MLB, Wrigley lost interest in the league, and in the fall of 1944 sold it to his colleague Arthur Meyerhoff for $10,000.

Meyerhoff — David Strathairn’s Ira Lowenstein in the film adaptation — proved to be a true ally, expanding the league and helping it reach its peak. Teams were added across the Midwest in Illinois (Peoria, Chicago, Springfield), Wisconsin (Milwaukee), Indiana (Fort Wayne), Michigan (Battle Creek, Grand Rapids, Muskegon, Kalamazoo) and Minnesota (Minneapolis).

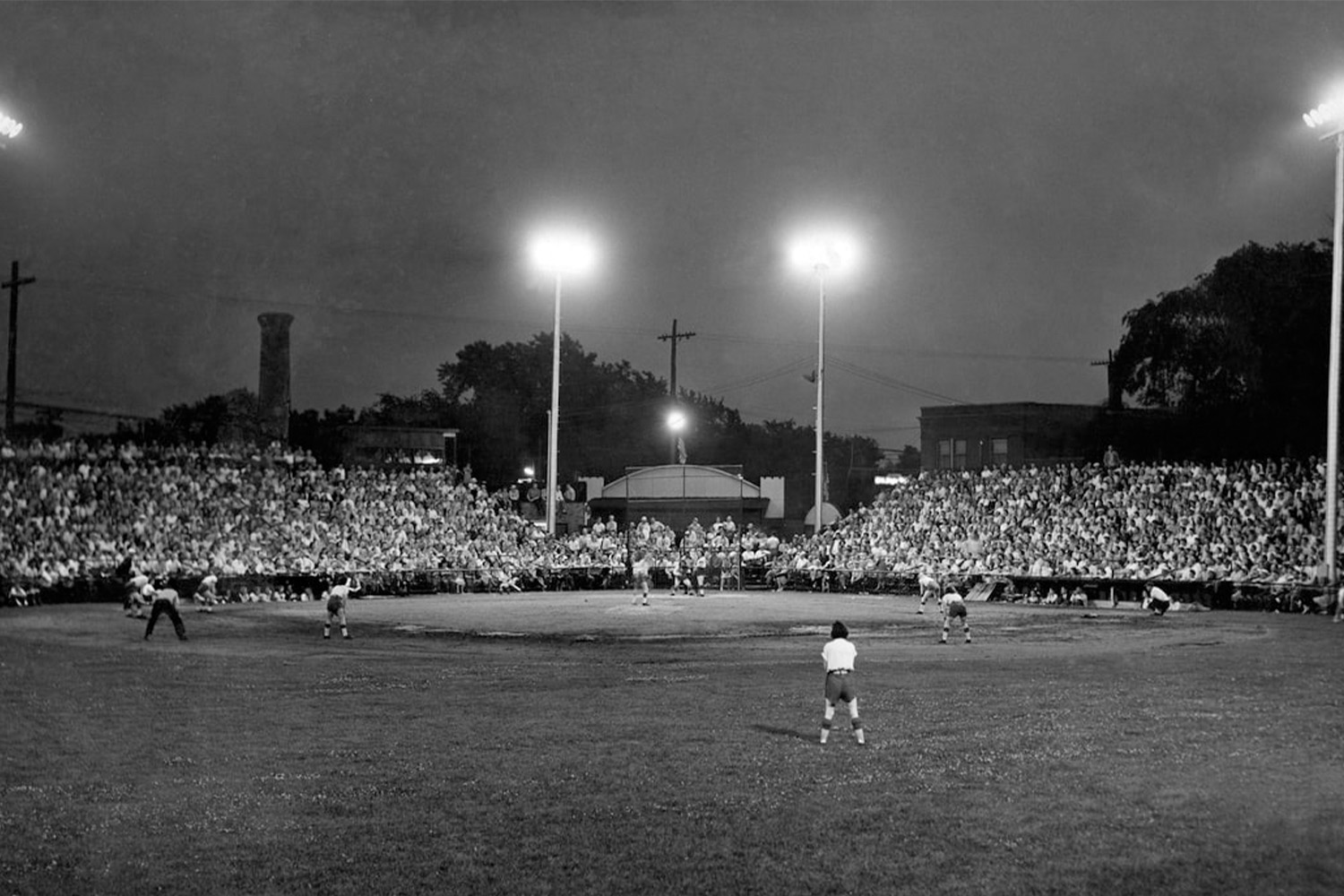

An advertising man, Meyerhoff pumped money into marketing efforts and media coverage and spectator attendance rose steadily, peaking at around one million paid fans in 1948, according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

And thus, a commercially-motivated decision by Chicago’s gum magnet became the start of women’s professional sports teams in the United States.

The Original Tryouts Were Held at Wrigley Field

Unlike the film depiction, tryouts were held in major urban areas around the country, explains AAGPBL Players Association Secretary Meriee Fidler. The 75 best ballplayers were then transported to Chicago for final tryouts and spring training at Wrigley Field. A week of work began on May 17, 1943 to funnel the women into four teams of 15. American and Canadian women were given contracts and girls as young as 15 made the rosters.

For the film’s part, Marshall was able to shoot these scenes in the Friendly Confines — if you haven’t watched Geena Davis’s Dottie Hinson unflinchingly snatch a fastball out of the air barehanded in a while, take a couple minutes to enjoy the spectacle.

Spring training wasn’t limited to the field however. Fresh off diamond work, the women had to attend charm school, because Wrigley was hell-bent on making sure his ballplayers were feminie. The league’s tired rules of conduct included clothing and styling requirements — no slacks in public and “lipstick should always be on.” Meyerhoff would, thankfully, discontinue this practice by 1945, allowing the athleticism of players to speak for itself.

Chicago-Area Teams Were the Best and the Worst in the AAGPBL

The film centers on the Rockford Peaches and rightfully so, as they were the most successful franchise in the league, winning a league-best four championships. (That’s 30 percent of all championships in the history of the league.)

While Rockford is a solid two-hour drive from downtown Chicago, the Peaches were closer to the city than any other franchise — plus they had Rockford Peach lifer Dorothy “Kammie” Kamenshek, who Sports Illustrated put on their list of top 100 female athletes…so yeah, we claim ‘em.

Kammie spent 10 seasons with the Peaches, helping them win all four championships and was one of the players used as inspiration for film character Dottie Hinson. A seven-time All-Star and two-time batting champ (1946 and ’47), the left-handed infielder led the league in putouts (10,440) and double plays (360). Oh and she’s the all-time leader in hits (1,090).

On the other end of the spectrum, there’s the Chicago Colleens. They joined the eastern division in 1948, playing their home games at Shewbridge Field on the south side, now home to Stagg Elementary School. Unfortunately, they finished their inaugural season in last place and promptly lost their franchise. The Colleens didn’t immediately disband, however, instead becoming a barnstorming rookie development team through 1950. Together with Springfield Sallies, the two teams traveled the country playing exhibition games, attempting to pick up new talent. They even played at Yankee Stadium.

Chicago Also Housed A Competing League: The NGBL

If you’re wondering why there wasn’t a Chicago team in the AAGPBL until 1948, it’s because Chicago already had large, active amateur leagues. Once the All-Americans went pro, several Chicago businessmen decided to get in on the action and convert the amateur talent to paid ballplayers. NFL owner Charles Bidwell and Oak Park businessman Emery Parichy established the National Girls Baseball League (NGBL), which operated from 1944 to 1954 with six Chicago-area teams. A few of the team names changed through the 11-season run, but the Bluebirds and Bloomer Girls were pillars, playing every year. Other teams included the Chicks, Rock-olas, Music Maids, Queens, Sparks and Cardinals — can’t go wrong with the state bird.

Players often bounced between the two leagues, following the best offers, but varied game regulations prevented them from competing head to head. Off the field, competition for talent was fierce, and player pilfering was so rife a poaching truce was introduced in 1946.

The two leagues had several notable differences:

- Pitching style. The major flaw in A League of Their Own is the incorrect implication that the AAGPBL started with overhand pitching. Women of the era were slinging 12-inch fastpitch, and unlike the movie, that’s how the league began. It wasn’t until 1948 that AAGPBL saw overhand pitching, with a 10-inch ball. The NGBL however, always stuck with underhand heaters.

- Travel commitments. “The attraction [of the NGBL] in Chicago was the ladies could work during the day and play at night, pulling in two salaries,” explains Carol Sheldon from AAGPBL Players Association. “The AAGPBL players were traveling constantly and couldn’t pull in additional salary until the offseason.”

- Racial integration. Unbound by the image-obsessed, constrictions of the “All-American” league, the NGBL was integrated, allowing for players like Chinese-American Gwen Wong, Japanese-American Nancy Ito, and Betty Chapman, the first Black professional softball player in the US.

The NGBL was definitely the female-empowered league, explains filmmaker Adam Chu, who is working on a documentary about the NGBL. “They let the players be who they wanted,” says Chu. NGBL players didn’t have to have chaperones, their uniforms were shorts, not skirts, and by 1953 two teams were managed by women — in 1954, there was even a female owner.

The NGBL packed their stadiums, their players were paid well, and they got to do it all in Chicago city limits.

Clearly, Chicago Was the Epicenter of Women’s Baseball in America

So to recap, two professional baseball leagues formed in Chicago, there was also a four-team minor league called the Chicago Girls Baseball League (CGBL) and dozens of amateur teams in the mix. “Softball in Chicago was huge,” says Chu, explaining the city hosted the annual World Amaetur Softball tournament. Forest Park was even called Girls Softball USA.

Why was Chicago so into baseball / softball?

We invented it.

Fiddler wrote the book The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. In it, she explains that softball was essentially created in Chicago by members of Chicago’s Farragut Boat Club in November of 1887. The game became so popular that by 1892, there were 100 organized indoor ball clubs in Chicago, and their games attracted thousands of spectators.

Then, another Chicago icon stepped in. Hull-House founder Jane Addams “maintained a constant campaign for the establishment of small parks and open school playgrounds to provide children a healthy place to play, to force light and air into the slums, and to improve their living conditions,” writes Fidler. Settlement houses and schools were the first institutions to support softball in its infancy, as Addams lobbied for Chicago school playgrounds to provide kids a place to play without the constant interruptions of play in the streets.

And so the game was intrinsically linked to the city of Chicago.

This article was featured in the InsideHook Chicago newsletter. Sign up now for more from the Windy City.