It’s 33 degrees today in Chicago — a good temperature for butchering, according to Lardon chef Chris Thompson, but not for curing, a task best carried out at about twice that. But the temperature won’t stop Thompson from his regular Thursday morning routine: putting up coppa, finocchiona and more for the pork-focused menu at his Logan Square restaurant, which decidedly and unapologetically breaks with plant-forward dining trends.

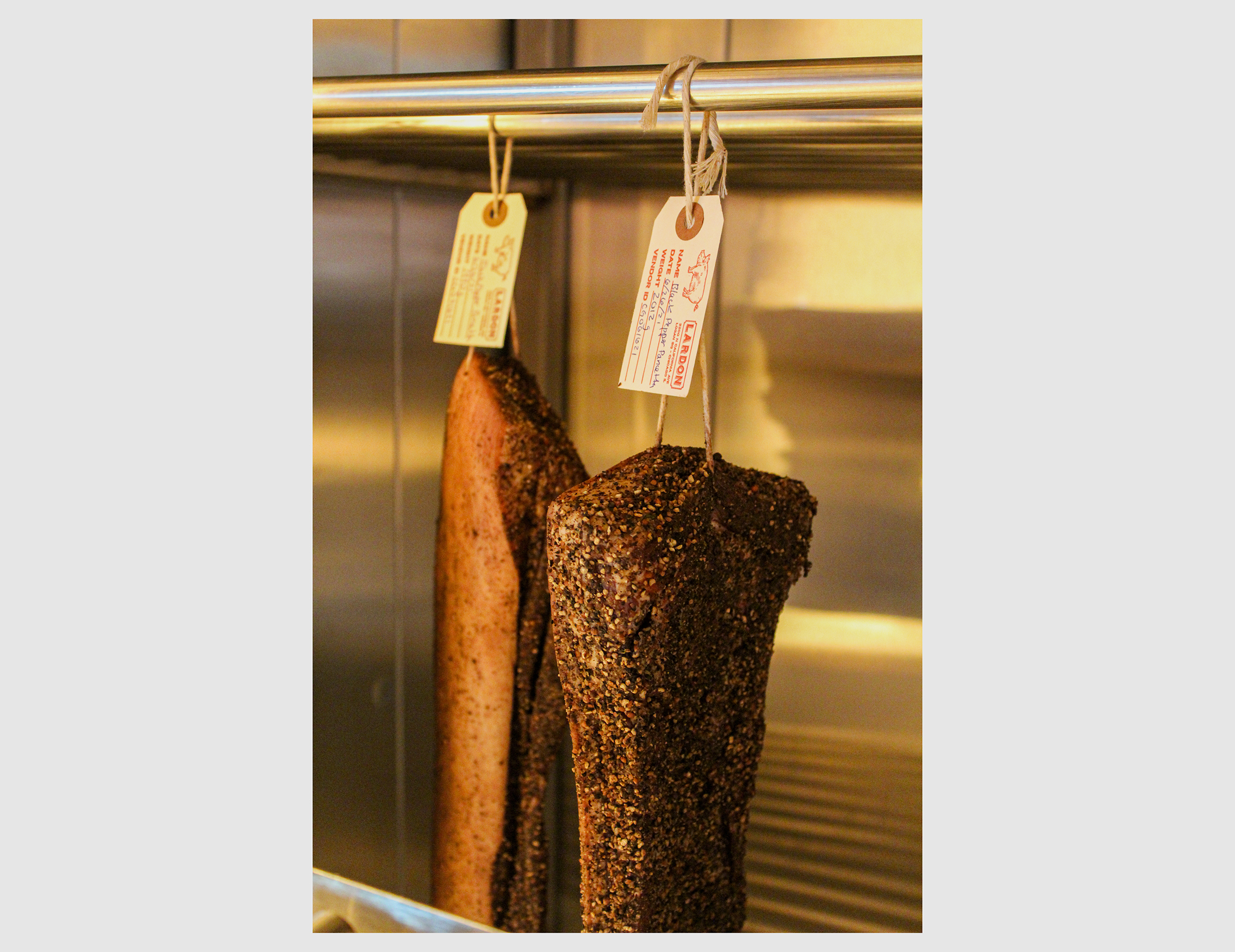

Thompson proudly leads the way through the curing room, a tight squeeze rendered even tighter thanks to the plethora of bresaola, prosciutto, salami and more hanging within — meats Thompson proudly refers to as his “babies.”

“We probably have over 3,000 pounds of meat in here, right now,” he says with a grin, most of which comes from whole hogs raised locally and humanely by Trent Sparrow of Catalpa Grove in Dwight, Illinois.

“Trent and I text every Sunday,” says Thompson. “I tell him what I need; he takes the animals to the slaughter facility on Monday. They butcher them as minimal as they can; they hang them for a couple of days. And then he picks them up at like 3 o’clock on Wednesday morning, and he drops them off here by about noon on Wednesday.”

Somewhere around 400 pounds of pork pass through these doors every week. From there, Thompson and his team get to work breaking it down.

“It starts with a whole animal on the butcher table,” he explains. “We’re cutting out the shoulders, then taking those shoulders, those coppas, and then marinating them, dredging them in curing salt, a little bit of dextrose for a little sweetness. And then we’ll vacuum seal those for a couple of weeks.”

When they emerge, they’re rubbed in a spice blend and hung until they’re ready to slice and serve. With two decades of experience under his belt, Thompson can tell a piece is ready just by touch.

Thompson first discovered the art of curing at Telluride, Colorado’s Rustico, relying on a secret spice blend prepared in Italy by one of the owners’ mothers.

“None of us really knew what was in it,” recalls Thompson. “It was like, ‘That’s Peppe’s mamma’s recipe, and don’t mess it up!’”

His technical prowess only grew from there, as he moved from restaurant to restaurant, learning not just the art of curing but even butchery, cut by cut.

“One thing I wasn’t afraid to do, early on in my career, is volunteer my time to learn from people that know how to do things that I don’t know how to do,” he says. In the kitchens at San Francisco’s Spruce, which he joined in 2008, he would regularly come in two or three hours before his sous-chef shift began to reap the benefits of the temperature-controlled room staffed by two full-time butchers.

“‘Hey man, show me how you do that.’ ‘Let me watch you do it a couple times.’ ‘Watch me do one,’” he recalls. “Working with people who know more than I do, volunteering my time to get the education on those things.”

When he made his way to San Francisco’s A16, with its narrow focus and strict adherence to tradition vis à vis the regional cuisine of southern Italy, “I was able to steer the whole ship,” he says. “I was able to put whatever we wanted on the menu … but still within that, like, that southern Italian focus.”

At Lardon, the rules are anything but rigid. To date, Thompson has featured no fewer than 17 different cured meats on his menu, ranging from the authentic to the esoteric. He loves gleaning ideas from out-of-print books he finds at flea markets or second-hand shops.

“The guy who wrote the book might not even be alive anymore, and you know he’s not working in a butcher shop,” he says, “but the knowledge is still there, for whoever wants to pick it up and try to carry that torch forward.”

He bolsters a few stalwart staples with a regularly revolving door of newcomers for about a dozen offerings at any given time.

“That room is only so big,” he laughs. “But we do have our signatures.”

Bresaola — a cured beef option — is one such staple; so, too, are Italian salumi like soppressata and finocchiona, the latter of which boasts the juicy flavors of red wine and underlying licorice aromas thanks to wild fennel. Trendy, spreadable ‘nduja is made with pork belly and loads of heat.

Pressed to pick a favorite, however, there’s no contest: Thompson is enamored with his coppa and its mouth-coating fattiness, nutty hints and balanced spice.

“I think that’s probably the piece of meat that I’ve made that I’m the most proud of,” he says. “I watch them hang in the room for four to six months, and it’s the one that I’m the most, like… ‘Come on! When are you gonna be done?’”

For his coppa, Thompson relies on a blend of spices sweet and savory, including a house-made chile powder fashioned from the tops of fresno chiles that he pickles for salads. The stem ends are dehydrated and ground for a kick that’s a tad spicier than cayenne — and also allows Thompson to reduce food waste.

It’s a philosophy that also applies to his approach to meat: aware of its heavy environmental toll, Thompson gleans every last bit of flavor. Livers are blitzed into a pork liver pâté; trotters form the core of a fried croquette; bones and skin are used to make a pork reduction to fortify different sauces.

“We use every part of it; nothing really ever ends up in the trash can,” he says, and then he laughs. “The bones, after we’ve boiled them for 30-something hours, we’ll throw those away.”

It’s no surprise, given all of the work that goes on in this little room, that the star of his menu is the charcuterie board — the item, he says, he’d most likely recommend to a first-time diner, showing off not just the coppa and bresaola, but also more offbeat offerings like head cheese, truffled lardo or filetto made with tenderloin cured in clove, thyme and garlic, for a robust flavor profile that offsets its comparative lack of fat.

“You think of all the meats like musicians on a stage, right?” he says. “You don’t want anybody screaming louder than the others.”

Thompson is clearly a master of his craft, yet it’s evident that he still considers himself a student. He hopes, with time, to perfect the French charcuterie that lends Lardon its name with as much expertise as he has Italian. His saucisson de campagne is one of his only French offerings, made with a four-spice blend and boasting slightly less acidity than some of the Italian meats on his menu. The recipe, which comes from a French cookbook from the 1970s, has undergone no small number of tweaks, due in part to the impossibility of finding saltpeter, a naturally occurring mineral rich in sodium nitrate, in the U.S. By his account, it took three attempts just to get the right cure.

“I really think that we have yet to put up our best French sausage,” he says.

For Thompson, curing is a “disappearing craft,” and one that he’s intent on keeping alive. And he has Chicago’s dining scene to thank, for without an audience, his craft would fall on deaf ears.

“I can come up with all this crazy, abstract shit, and if nobody wants to eat it, then it’s a waste of my time,” he says. “But thankfully we have an amazing food culture here in Chicago, and I think that has a lot to do with the history of the chefs that have come before me here, and encouraging and enticing people into trying things that might be out of their comfort zone.”

And as a chef, he’s willing to put in the time and effort to give Chicagoans only the very best.

“So much of the cooking I’ve done in my career has been, immediate reward, cause and effect, you do this today, it’s done today,” he says. “Whereas meat, curing it’s a waiting game. And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve tried to learn more patience. Doing cured meat helps tie into that.”

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.