Earlier this year, Nikil Saval won the Democratic primary for a Pennsylvania State Senate seat in Philadelphia’s 1st District. Like a number of young candidates running for office as Democrats, Saval is passionately pro-labor and a democratic socialist, with the endorsement of one Bernie Sanders behind him. Unlike many of his peers, however, his background isn’t solely political: he’s also a former editor of the journal N+1.

That blend of literary chops and political acumen might seem like an unexpected mix, and it’s true that few high-profile literary figures go from writing about politics to making the decision to run for office. This applies to writers on both sides of the political divide: on the conservative side of the political spectrum, Hillbilly Elegy author J.D. Vance hinted at a possible run for office, but so far has opted not to run.

That’s not to say that Saval is alone in moving from the printed page to the ballot box. Novelist and political commentator Gore Vidal is remembered today for his books and heated public debates with William F. Buckley, Jr. (more on him in a moment). But Vidal also ran for office twice. In his 2012 obituary for Vidal, Charles McGrath noted that the writer had both the electoral experience and the demeanor of many an elected official — though he lacked the actual votes to get himself into office.

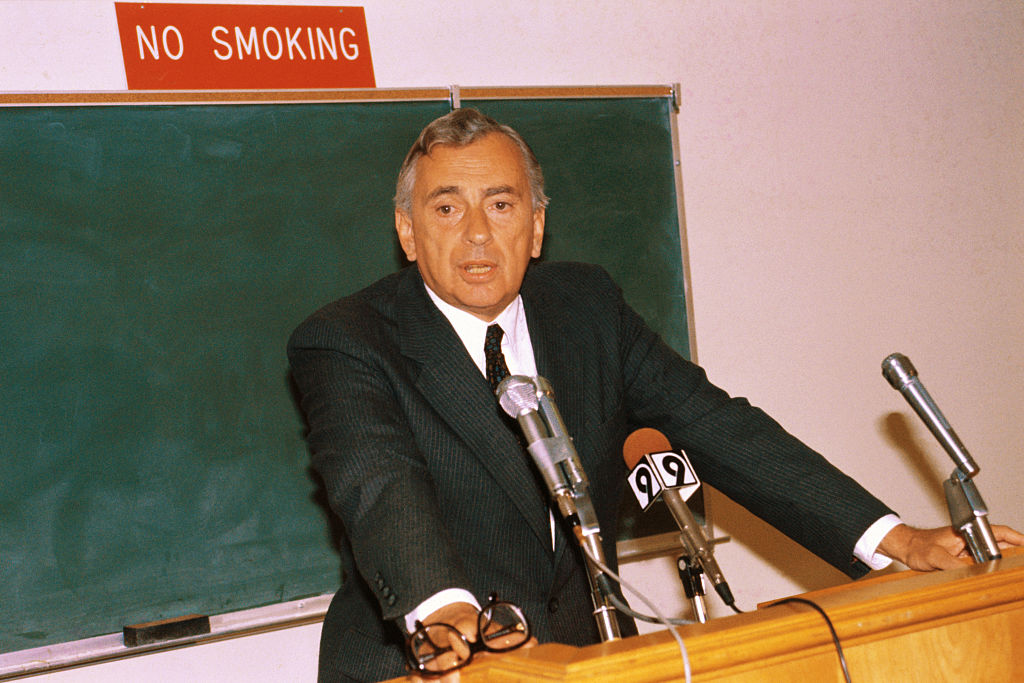

“He twice ran for office — in 1960, when he was the Democratic Congressional candidate for the 29th District in upstate New York, and in 1982, when he campaigned in California for a seat in the Senate — and though he lost both times, he often conducted himself as a sort of unelected shadow president,” McGrath wrote.

If Vidal’s first run for office opened the 1960s with an overlap of literature and politics, Norman Mailer’s campaign for mayor of New York City bookended it in 1969. Mailer wasn’t the only writer on the ticket, either; noted columnist Jimmy Breslin was also along for the ride. All told, he received 41,000 votes in that year’s Democratic primary, thus ending his political career. That Mailer, a man who had stabbed his wife nine years earlier, was a somewhat serious candidate for office speaks volumes about the era — though it also remains a bizarre footnote in city history.

Mailer wasn’t the only writer to run for mayor of New York in the 1960s, though. Four years earlier, conservative author and National Review founder William F. Buckley, Jr., threw his hat in the ring for the same office. Buckley ran on the Conservative Party ticket, leading to what a 2005 article on the campaign dubbed “one of the most memorable elections in New York history.” Buckley went on to win 13.4 percent of the vote; he also wrote a book about the experience.

Instances where acclaimed writers pivoted to public office have also occurred closer to the present day. British writer Rory Stewart is the author of a number of acclaimed memoirs about his works and travels in Asia and the Middle East, including The Places in Between, about traveling across Afghanistan on foot in 2002. Stewart joined the Conservative Party in 2009, and spent the next decade in Parliament. He eventually resigned from the Tories over Boris Johnson’s Brexit policy, bringing an end to his time in office.

While their political careers were characterized by intra-party clashes, Stewart and Johnson do have something in common: both had published books before their time in office. Boris Johnson’s entry into public life came as a journalist, and before his time as Prime Minister, he had published a number of books, including an overview of the life of Winston Churchill.

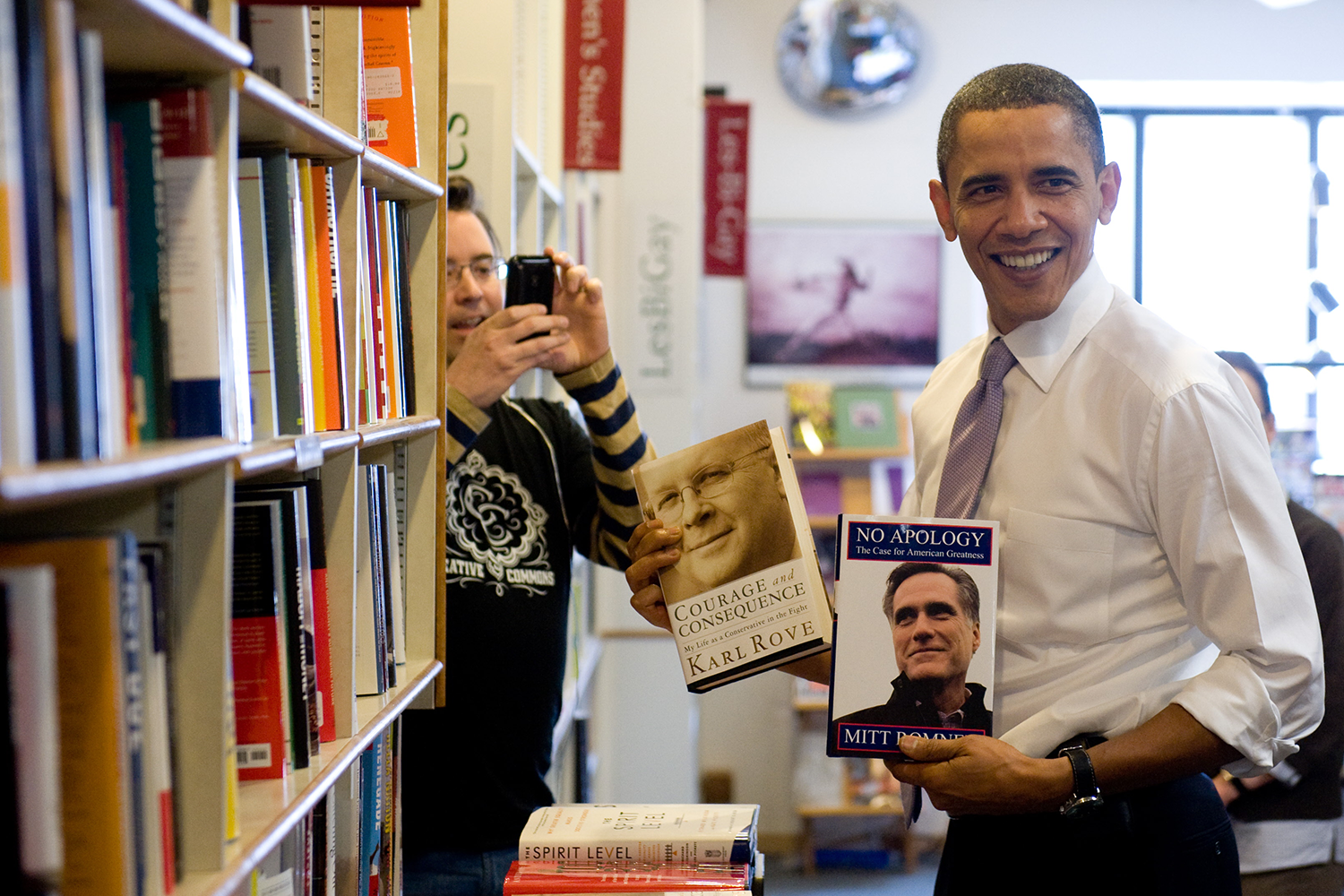

That selfsame arc can be seen on the other side of the Atlantic as well. When Barack Obama’s memoir Dreams From My Father was published in 1995, Obama was an academic who hadn’t yet run for office. An article from the History Channel notes that “[t]he book received favorable reviews; however, it sold a modest 8,000 to 9,000 hardcover copies and went out of print within several years.” Some writers-turned-politicians never quite get that second career to work out; others find a second act that far eclipses the first.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.