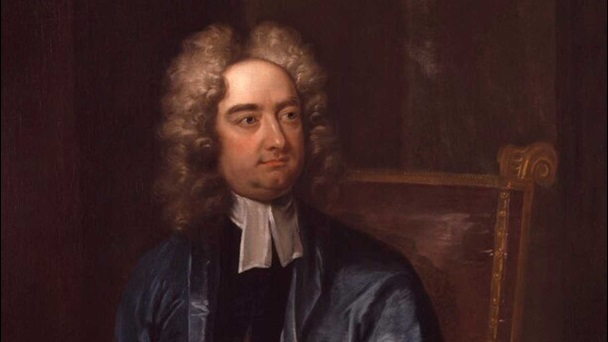

Before there were hot takes, there was contrarian writing. Arguably the apex of this came in 1729, when Jonathan Swift penned “A Modest Proposal,” in which he proposed a solution for the famine currently underway in Ireland: eating the children of the poor. It was an eye-catching approach to be sure, satirical in some ways and politically charged in others. It involved a kind of “everything you know is wrong” rhetoric, challenging readers in myriad ways.

The contrarian literary tradition has continued in the centuries since. Notably, the late polemicist Christopher Hitchens’s contribution to the Art of Mentoring series of books was titled Letters to a Young Contrarian (more on him in a moment). Other storied writers, such as Ellen Willis, also wrote in a way that was difficult to pin down but made for a number of memorable challenges to complacency. But a number of factors have made it harder for writers working in a contrarian vein in recent years, from hyper-partisan politics to a media landscape that tends to deal exclusively in sensationalism and absolutes. Alternately: If Jonathan Swift wrote “A Modest Proposal” today, would he end up ratioed?

Contrarian writing can involve proposing a seemingly right-wing provocation to advance a left-wing argument (or vice versa). It can involve challenging canonical works of art or arguing against the status quo in profound (or, at least, seemingly profound) ways. And the last few months have seen the release of a number of books that advance contrarian arguments: Christopher Ryan’s Civilized to Death: The Price of Progress; P.E. Moskowitz’s The Case Against Free Speech: The First Amendment, Fascism, and the Future of Dissent; Jess Row’s White Flights: Race, Fiction, and the American Imagination; and Bari Weiss’s How to Fight Anti-Semitism.

These books have very little in common, ideologically. But reading all of them is an experience of challenging preconceived notions. Are they all effective? That will depend on the reader — which also happens to be one of the challenges inherent in contrarian writing: Who, exactly, are they writing for?

“I was quite young when it first occurred to me that the culture I was born into was out of balance, and that there was something seriously wrong about our approach to life,” says Christopher Ryan. His previous book, a collaboration with Cacilda Jethá, was Sex at Dawn: How We Mate, Why We Stray, and What It Means for Modern Relationships, an anthropological foray into humans and sex. In many ways, that helped lay the groundwork for Ryan’s next project.

“Lots of the feedback I received from readers included a request for more information about other, non-sexual aspects of hunter-gatherer life,” Ryan explains. “People seem to be hungry to understand where we come from, and to use this knowledge to better understand how to tweak their lives in ways that will lead to greater meaning, depth and contentment.”

The argument that Ryan makes in Civilized to Death is right there in the title: that many of the trappings of modern Western society have made humans more miserable and less happy. He explores the earliest human societies with an eye toward the ways in which they were more fulfilling and egalitarian than the way many of his readers currently live. The primary benefit of the modern world, he notes, is a lower infant mortality rate (onetime political science majors and Tolstoy buffs may note some overlap between Ryan’s arguments here and anarcho-socialism). And while Ryan’s arguments are clear-headed and written in a neatly arranged style, he’s also making a bold argument: namely, that almost everything about the way we live today is a fundamental betrayal of how we should be living.

Moskowitz’s The Case Against Free Speech, in turn, opens with an equally big premise: that the concept of “free speech” that many readers have internalized is not nearly as free as they might believe. As they write early on, “This book is not anti-free-speech. It is anti-the-concept-of-free-speech. It’s an important distinction. Everyone should have the right to say what they want. I will not argue otherwise. I am not an authoritarian.”

Moskowitz’s book opens with a harrowing account of the rally and protests in Charlottesville that led to a white supremacist killing activist Heather Heyer. They make the case here that the government has always constrained speech in some way, and that many of the groups making the case for free speech are coming from the right-wing side of the political spectrum.

Most convincingly, Moskowitz makes the case that there’s a “double standard” in terms of how certain conflicts over speech play out. “It’s national news when someone like Charles Murray or Steve Bannon is not allowed to speak on a college campus,” they write. “Their rights eclipse the rights of so many others in mainstream discourse: Dakota Access Pipeline protesters, or J20 defendants, or Black Lives Matter activists.”

The four authors discussed here are all making contrarian arguments, but it would be deeply inaccurate to paint them as ideological cohorts. Among the public figures critiqued in Moskowitz’s book is Bari Weiss, currently an editorial columnist for The New York Times. Weiss’s How to Fight Anti-Semitism also opens with a powerful allusion to a recent tragedy: in this case, the 2018 shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, in which 11 people were murdered.

Weiss’s approach here is to provide a kind of taxonomy of anti-Semitism, beginning with its adherents on the political right and moving from there to anti-Semitism on the political left and in the Muslim world. “I do not think the best use of any minority’s time and attention is to focus on their haters,” Weiss writes. “But I think it is worthwhile to understand and analyze this disease of the mind, in its various permutations, for one reason: because I want us to fight it.”

Weiss’s book is a relatively short volume, and there are times where some of her arguments might be better served by more space to develop. And while her structure allows for an “a plague on both your houses!” argument, in which Weiss can critique both ideological sides, it does make it a little curious when she equates, essentially, a college student being critical of Elie Wiesel with the anti-Semitism of various advisors to the Trump administration.

Political or ideological arguments aren’t the only way in which a writer can make a contrarian argument. In White Flights, Jess Row explores the unspoken presence of race in the work of a number of notable American writers, including Anne Tyler, Raymond Carver and Marilynne Robinson. In this case, it’s not so much an “everything you know is wrong” approach as one reminding the reader that there are dimensions to these authors’ work they may not have considered.

Row rejects the “contrarian” label for this book, however. “The word ‘contrarian’ makes me think of writers (often from a privileged position) who represent themselves as consistently going against the grain or questioning the popular consensus — writers like Christopher Hitchens, Camille Paglia, Meghan Daum, Thomas Chatterton Williams, Bret Stephens,” he says. “I don’t identify with that rhetorical tradition at all. I’m interested in linking up ideas and arguments with existing popular movements, not operating from a position of eye-rolling and scorn that reinforces the status quo.”

Row also notes that his essay “What Is The Point of This Way of Dying,” contained within White Flights, is his method of addressing the difference between those two literary traditions. He describes the work he’s done here as “a hybrid of cultural criticism and autobiography, or, as it’s sometimes called, auto-ethnography.” Row’s choice to adopt this method was simple, in his mind. “I wrote it that way because there was no way for me to be detached from the subject, or for me to step aside from my own very particular literary education as a white male writer who started studying fiction in the early 1990s,” he explains.

As for the response to the book, Row mentions that it’s been more measured than he expected. “I’ve had reviews that have taken the book to task in different ways, not surprisingly, but overwhelmingly the feedback from readers themselves has been very positive. I haven’t heard from people eager to defend, say, Gordon Lish, or Marilynne Robinson or Richard Ford. Though I’m sure they’re out there.”

He adds, “if you’re reading this, I’d like to hear from you.” Row might be writing against expectations, but he’s also up for a good discussion.

The current publishing landscape is one that tends to support ideological consolidation. A 2017 article in the New Republic noted that conservative publishing was increasingly becoming a self-contained entity; the term “preaching to the choir” can come to mind. One of the reasons Hitchens comes to mind as a reasonably successful contrarian writer is that his politics were notoriously difficult to pin down throughout his life. And today, the number of conservative or liberal writers not writing for an explicitly conservative or liberal audience is relatively small. (One exception might be Weiss’s New York Times colleague Ross Douthat, whose forthcoming The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success will be released on the same imprint as Ryan’s Civilized to Death.)

That landscape carries over to online spaces, where there’s a cottage industry of taking quotes out of context and spinning them into think-pieces. A brief controversy last year, when a quote David Lynch made about the Trump presidency was interpreted as an expression of support, is particularly instructive. And an innate part of contrarian writing is a tendency to make bold pronouncements and risky declarations. Publishing a contrarian book in 2019 requires an audience that will take in the entire argument, not just embrace the most potentially salacious bits. It’s likely why Moskowitz begins their book with an explicit declaration of their feelings on speech in general.

When Ryan speaks about the challenges of writing a contrarian work, his response is direct: it “is that people don’t want to hear more bad news. They’re already saturated with doom and gloom.” For him, the countervailing argument might just win out.

“Everyone wants to believe in progress, and that they’re lucky to live in the best time and place ever. That’s natural,” he explains. “But when you’re going in the wrong direction, progress is the last thing you need!” It’s hard to think of a more contrarian argument — but, as Ryan’s argument shows, sometimes a little contrarianism is needed to make the world a better place.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.