Despite its status as one of the most famous independent bookstores in the world, even the Strand in New York City is barely making it through the COVID-19 pandemic. After a temporary shutdown, mass layoffs and a limited-capacity reopening, sales at the 93-year-old New York City fixture were down 70 percent, leading third-generation owner Nancy Bass Wyden to issue a public plea for help from customers. Strand supporters turned out in droves, driving record sales in the ensuing days, but still questions about the store’s future remain, as do tensions between Bass Wyden and her unionized employees.

The rescue of a beloved independent business should be one of the few heartwarming stories of 2020’s incessant ravages. But the Strand is a singular entity in this retail niche for reasons that go beyond its fame and fortune. What also makes the shop unique is Bass Wyden’s marriage to a Senator, which makes her financial transactions — including millions spent in stock purchases, with well over $100,000 going to ostensible competitor Amazon — a matter of public record. That fact might not matter to the average customer, but it cuts deep for the Strand’s workers, who’ve seen around 100 of their colleagues laid off this year. Why, they wonder, are their fellow employees still out of jobs while the owner gets a government payroll loan and has the money to invest elsewhere? It’s a sentiment shared by many loyal supporters of the store on social media, with some even accusing the owner of taking the loan to line her own pockets.

Bass Wyden, whose grandfather launched the business in 1927 and is now married to Democratic Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon, says she needs to spend money to make more money while the Strand isn’t performing, a means to keep it afloat in the long term. The workers, who’ve already battled her on issues like providing sufficient personal protective equipment for employee and customer safety, see her putting her personal wealth before the institution. The truth, it seems, lies somewhere in the middle, with both sides wanting the store to live forever and, in true 2020 fashion, having their nerves frayed to the limits.

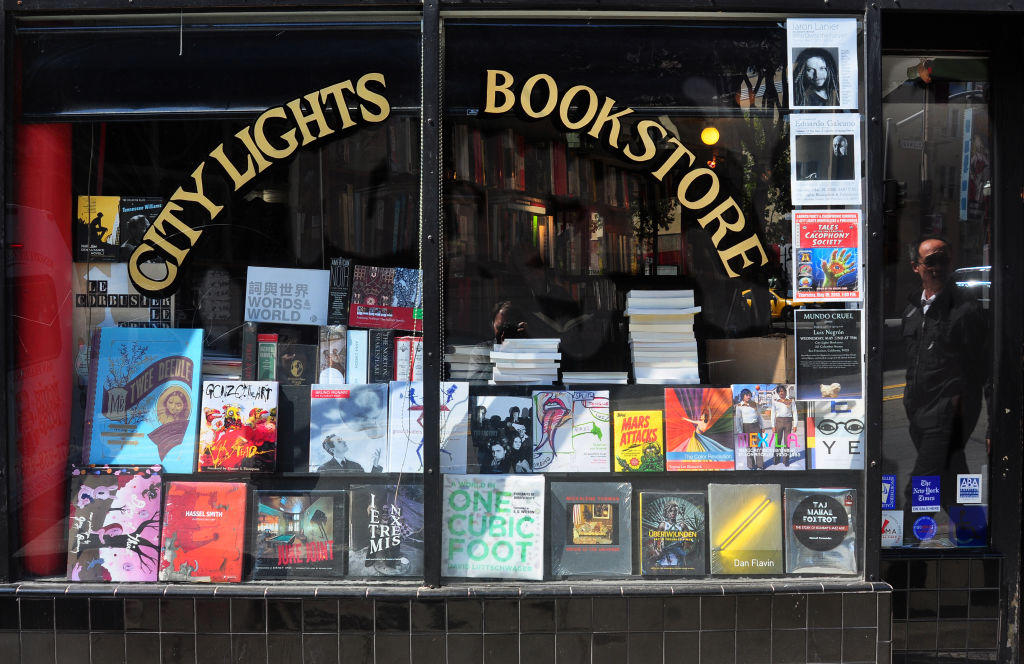

Going into 2020, independent bookstores seemed to have a steady foothold in their small-yet-beloved niche of the retail industry. Many of those that outlived the big-box store and then survived the fallow era of the late-aughts recession found ways to combat the ease of readers buying from etailers like Amazon or the impersonal shopping experiences of Borders or Barnes & Noble by becoming more than just a store. If they had the space, they’d offer events like author readings or discussions of a new or timely title fueled by coffee and/or wine; the smaller ones played up their staffers’ knowledge to curate recommendations based on a customer’s taste in ways no algorithm could, the art of the handsell. In 2018, the American Booksellers Association reported these indies, on average, saw a five-percent growth in sales compared to the prior year, corresponding with a “49 percent growth in the number of stores” in the previous decade, according to a Harvard Business School study.

Then, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Although “print unit sales rose 6.4 percent for the nine months ended Oct. 3, 2020 over the comparable span in 2019,” according to Publishers Weekly, the cratering economy, federal and state government inaction, and the lack of foot traffic in physical spaces due to shutdown orders, capacity limits and consumer fears forced many indie stores to shutter. According to the ABA, the average is now one bookshop going out of business per week.

The Strand wasn’t immune to the havoc the coronavirus wrought, either. Even after reopening in late June when the state and city governments allowed, sales were down by around 70 percent. That led the store to tweet for customers to come back or put in online orders, writing in a statement that the business was becoming “unsustainable,” Bass said, “[F]or the first time in the Strand’s 93-year history, we need to mobilize the community to buy from us so we can keep our doors open until there is a vaccine.”

Complicating matters was the fact that Bass Wyden had gotten a Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan of between $1 and 2 million to retain 212 employees, rehired 45 employees for the June 22 reopening, but then laid off 12 of them on July 9, per Gothamist. “One of them just put his wife and kid back on the health insurance. It’s cruel and it doesn’t look good,” says Melissa Guzy, a fifth-year bookseller and union shop steward for the United Auto Workers Local 2179, which represents about 170 current and former Strand employees. “When you’re trying to make your workplace successful and the person that runs it undermines the efforts of the people trying to improve it, it becomes difficult.”

That second purge led general manager Eddie Sutton, an employee since 1991, to quit in protest, and other tensions soon emerged. The rehired workers complained for weeks that Bass Wyden refused to spend money on equipping the returning staff with PPE and outfitting the store with acrylic barriers to impede COVID transmission. In July, other laid-off employees picketed outside the Strand’s newly opened Upper West Side location, chanting “We get sick, they get rich!”

For her part, Bass Wyden admits that she underestimated the pandemic’s effects on business and the city. “We thought, ‘Oh, we’ll come back June 1st. Then it came to the point where we’re like, ‘Oh no, this could be for the long haul,’” she tells InsideHook. “In our 93 years, we’ve never laid off a single person, and that’s even going through the Depression. There was a [sense of] ‘How do you lay off a person?’ and what does that mean, to furlough a person? ‘How much are they going to get in unemployment?’ I tried to write to the Mayor’s office to make us an essential business and get some politicians to do that, and I didn’t get anywhere. I mean, I gave everybody healthcare for a month and a half. I tried to conserve money, but I guess if everybody knew that it really wasn’t even going to be back to normal at the end of October, it would have been a whole different thing.”

On that point, there have been misconceptions — and some false accusations — that Bass Wyden took PPP money to fund her personal stock portfolio. As Will Bobrowski, an 18-year Strand employee and union shop steward, tells InsideHook, Bass Wyden told him that the average union employee cost her $5,200 a month in salary, insurance and taxes. If the Strand only had 30 union workers on its payroll from July 1st to the present, it would’ve spent $624,000, but per Bobrowski, they’ve had more dues-paying staffers than that at various points, plus non-union employees in management and, as Guzy says, outside consultants who work in marketing and design and on the store’s website. The online division is getting bolstered, especially since the website crashed in the days following Bass Wyden’s open letter.

“We’re following all the terms of the loan agreement with the goal to get as close to the original headcount as possible before December 31,” Bass Wyden says of the PPP money. “The reality is, if we would’ve taken back all of our employees, we would have burned through the loan in a month, easily. Sustaining this store has become a marathon with no end in sight. We had to stretch every penny to try to make the loan work. So, it was helpful and we didn’t use it all up. We’re hiring people now, thanks to the public outpouring.”

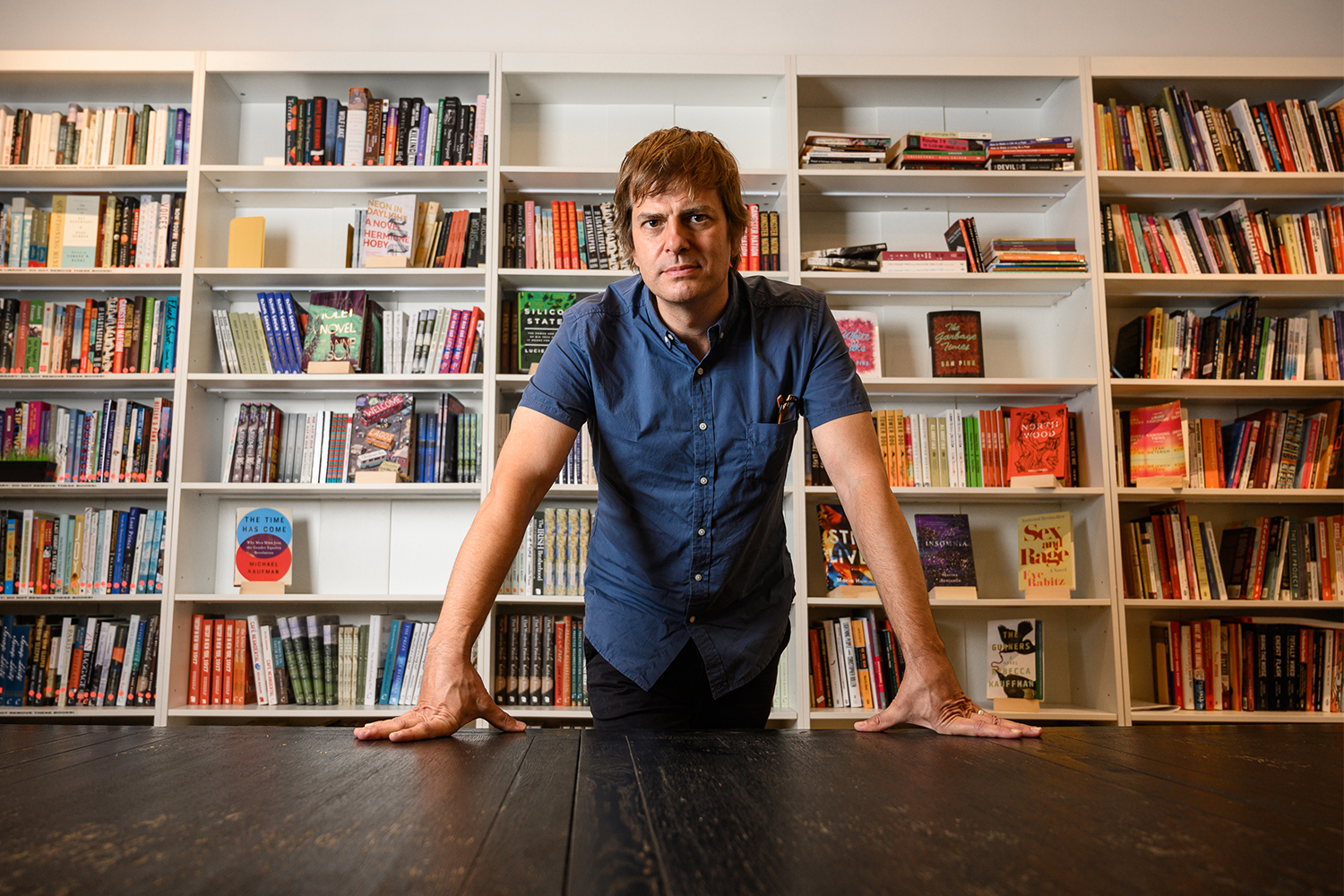

It’s a position that Christine Onorati sympathizes with, to a point. The owner of WORD, an independent bookseller with two locations, one in Brooklyn and another Jersey City, she’s retained almost all of her employees throughout the lockdowns. “All I can say is that we are all in a really terrifying position right now. The looming fears of another lockdown will likely be a death sentence for many of our businesses,” she says. “The margins in bookselling are some of the worst in retail; online orders are wonderful but they take more time and labor to process for even less profit. Our indie systems weren’t set up for this massive online shift, and I know from talking to all my bookselling friends that most of us are just scrambling to stay above water.”

When it comes to Bass Wyden’s open letter and stock buying, Onorati says, “I have always shied away from the concept of bookselling-as-charity, but I think the time is coming where we will have to send up the flare that we are legitimately struggling and that the indie-bookstore world will be radically altered if people don’t keep their book purchases in the indie channel and stop supporting Amazon. That to me is our biggest threat.”

Meanwhile, Bass Wyden, who says she puts $2 million of her own money into the store every year, doesn’t regret buying any stocks, including Amazon. “As a small business owner, I’m just trying to maintain operations during difficult times. I need to diversify my personal portfolio, so I invested in stocks that were performing. I have to have the resources to keep the stream going. I put aside money, we went through all of this, […] we lost 70 percent of our sales. I can keep it sustaining up to a point, even though we own the building. And I’ve been subsidizing the rent for the store forever, so that’s why I asked the public to help.”

Despite being at odds with Wyden and overwhelmed by the amount of customers, the Strand staff is grateful to see so many people turning out to save the store. “We all want it to work. We all want it to succeed,” says Bobrowski. “We all want our jobs to continue. And it’s not just our jobs — it’s a family. I don’t mean the Bass [Wyden] family. Our desire to see this continue has nothing to do with loving to make Nancy Bass Wyden money. We care about all our friends who were laid off. We’re a tight-knit community. We all know each other, and half of us live with each other. Plenty of people are dating or married to somebody they met here.”

Guzy adds that what the employees want most is transparency from Bass Wyden, and for the owner to understand how her actions are affecting the employees. “How do you communicate to somebody that you have to invest back into your own business after 93 years? We shouldn’t have to explain that,” Guzy says. “If the Strand goes under, it won’t be from lack of support of the community or from the economic downturn — it will be because of her. We’re doing everything we can to prevent that from happening and trying to, even if it feels futile at times, dare to see the light. We can make this work.”

When asked if she’ll use more of her wealth to bolster the store’s coffers rather than buy more stocks, Bass Wyden simply says, “I put in so much already.” She then adds, “I’m doing my best. My goal is, as the leader of a company, to keep this place going so that the staff can have jobs, so that the customers can buy books, and, be part of an ecosystem where you’re supporting writers, you’re supporting the publishing community.”

For now, the Strand will have to rely on that continued support through the rest of 2020 to offset its earlier losses and survive into its 94th year. “I’m elated,” Bass Wyden says of the recent outpouring. “I’m going to take it day by day. We know we’re going to be busy putting together all these orders for the holidays. Then I can only say, after that, I hope we will find a way to sustain this.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.