In 2023 we are inundated with prequels, sequels, reimaginings, remakes and continuations. Most are unnecessary. Some are painful.

But occasionally, something is added to a fictional world that already seemed complete and provides more depth and weight to the original work.

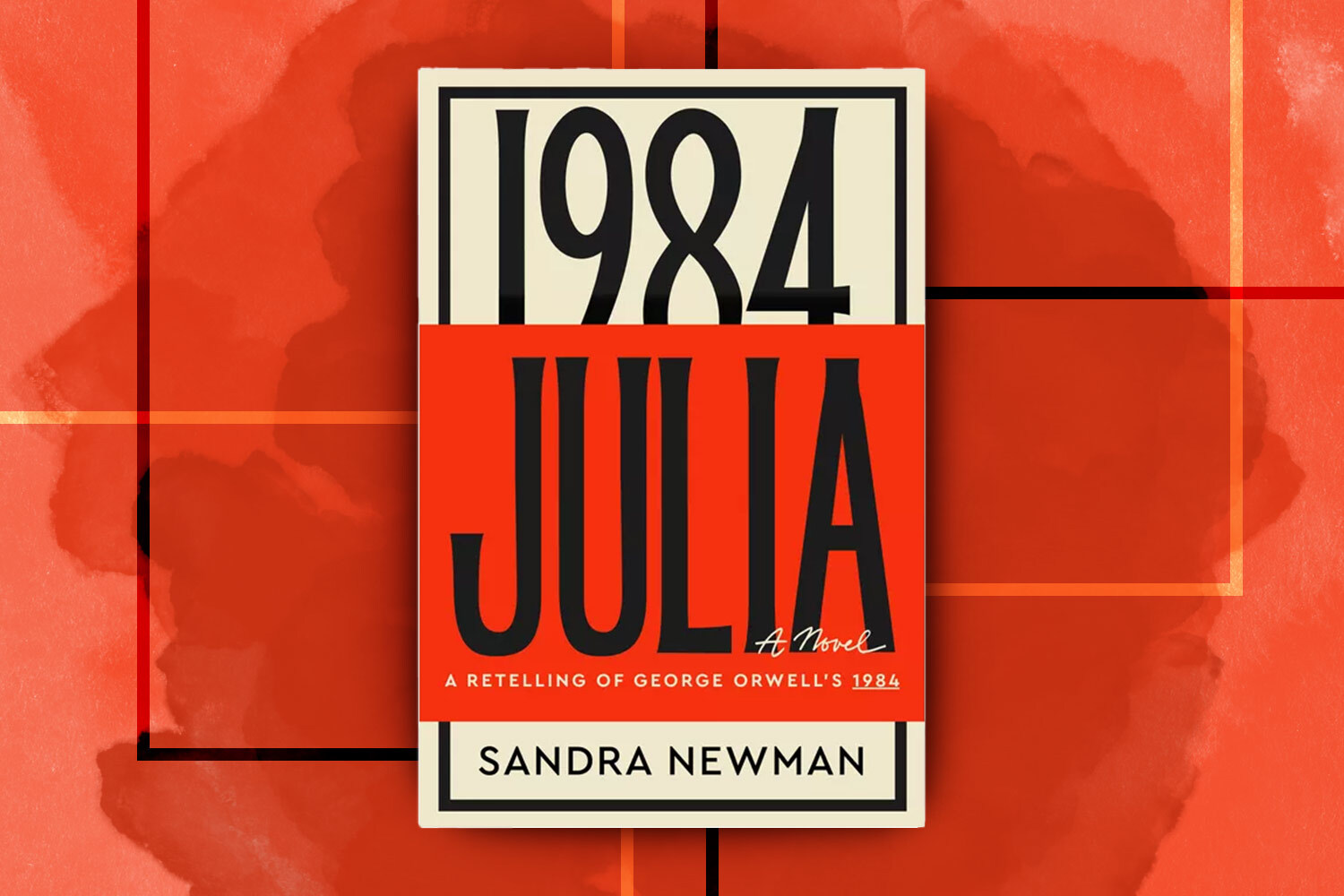

While definitely intrigued by Julia, an officially sanctioned “retelling” of George Orwell’s dystopian classic 1984 by critically acclaimed author Sandra Newman (The Men, The Heavens), I questioned its need. But after reading the book — Orwell’s tale retold from the point of view of Winston Smith’s lover Julia Worthing — I saw it as an almost necessary recalibration of the original, which certainly did not present much of Julia as a character.

Here, Julia has real depth and explores relationships, political musings and even the concept of hostility (often toward Winston) that’s implied or absent from Orwell’s novel. And Newman expands on the concepts of Oceania, Big Brother, Newspeak, the “proles” and other 1984 staples, showcasing a world that’s even more heartbreakingly cruel for women than men — no surprise that Mariner Books is marketing Julia as a “feminist retelling.”

Orwell’s “1984” to Get “Feminist Retelling” From Julia’s Perspective

“Julia” will recount the events of Orwell’s classic from the perspective of Winston Smith’s love interestNewman admits some modern dystopian novels inspired her — I would have thought The Handmaid’s Tale but she gave a far more interesting answer. But this is a novel that manages to both feel very of the moment but also could have been written a few years after 1984’s publication. The book does its own world-building (it even continues beyond where Orwell’s novel ended, in a surprising way) but stays consistent with the politics, technology and general worldview of its original novel.

Which is depressing, given that in the 74 years since the novel’s publication, we’re in a space that feels equally bleak and familiar. Below, our interview with Newman on how Julia came to exist.

InsideHook: What was the process of getting the right to do a continuation of 1984?

Sandra Newman: The Orwell estate approached me. The idea of a book from Julia’s point of view had been in the air for a very long time, and they decided that, with the copyright of 1984 running out in the UK, this was the last time they could have real influence on how it was realized. So they looked for someone they trusted to write the book in a way that wasn’t going to cheapen Orwell’s work or pervert his message.

They did have me write a chapter and an outline before they went public with the endorsement. To be clear, the Orwell estate didn’t meddle with my writing, and they don’t profit financially from this arrangement. I found a publisher separately, and after a few initial conversations, the estate left me to write the novel as I saw fit.

How much world-building were you allowed?

Orwell actually leaves a lot of blanks that almost seem like deliberate writing prompts. He talks about proles and tells us that they are much freer than Party members, but we see almost nothing of their lives. He mentions that Julia lives in a hostel with 30 other women, but we learn nothing about what that little society is like. Julia’s previous job, as she tells Winston, was at Pornosec, where pornographic novels are produced for proles, but all we hear about the novels is that they’re “boring.” (To me, the nature of the porn produced in this world cannot be boring.) He tells us that the Party is in the process of replacing sex and marriage with artificial insemination as a source of babies, but never shows us how it works or what giving birth to these babies — which are destined to be taken away from their mothers and raised by the government — feels like.

There are so many unanswered questions: What is life like in the countryside? How did Big Brother come to power? In short, what Orwell mentioned in the book was ultimately less of a constraint than it was a series of amazing ideas.

What was the appeal of writing this from Julia’s perspective?

Julia is a completely different sort of person from Winston Smith. She’s a pragmatic, earthy, fearless person, who is as capable of living happily in Oceania as anyone could be. She doesn’t get hung up on politics and has a (mostly well-hidden) contempt for the entire subject. She hates the Party because they’re swine; that’s all she needs to know and she doesn’t understand Winston’s obsession with understanding things. But she does know a lot more about the ins and outs of the world than Winston: she has had many lovers before and has somehow managed to get away with it; she is the one who buys goods on the black market; she is always setting Winston straight about some fact of life.

She’s also in a completely different position from him. She lives in that hostel, she’s a member of the Junior Anti-Sex League, she’s a candidate for artificial insemination; she sees sides of this world that he never sees and frankly isn’t that curious about.

In 1984, she’s a bit of an enigmatic figure. It’s unclear why she does all the things she does; it’s even questionable whether Winston was right to trust her. What did she see in Winston? If she’s so uninterested in politics — Winston says she’s “only a revolutionary from the waist down” — why does she go along with him when he wants to join the Brotherhood?

I noticed Winston became even less important in the book as it continued — other characters were equally or even important (Vicky, for example) to Julia’s story. Was that a conscious decision by you or as you were writing did you feel like there were more characters to explore?

Winston gets quite thoroughly explained in Orwell’s book, so I really had to go in a different direction and explore new territory. And the other characters are really interesting. My general impression, from working with 1984, was that Orwell didn’t have room to do justice to all the material. He has all these wonderful inventions like the Junior Anti-Sex League, but they’re just mentioned and we never see them. Or a character like Parsons, whose two children have been taught by the Party to be avid informers and denouncers of adults; what is life like for him? He seems to love his awful children, so what is that like? Orwell didn’t have the room to go into that, whether or not it interested him. I have the advantage that 1984 had already been written, so I had time to expand into the other areas of the world that it barely touched.

Did you have empathy for the characters? I found I had more for Julia and much less for Winston after reading this.

I have enormous empathy for the characters. I really think we can’t condemn people for what they do when they’ve spent their entire lives under physical threat, compulsorily attending hangings and seeing people being dragged into police vans all the time, with every conversation haunted by fear. There’s a line toward the end of the book where someone says, “One has no choice, and yet one must live through it exactly as if one had.” That’s more or less how I feel about it. There are brief moments when people show extraordinary courage and kindness in this world — and those moments exist in real totalitarian governments too. But for me, the moments of everyday betrayal are also horribly poignant.

When writing the book, Orwell was influenced by WWII, Stalin, etc. (and Jura). Did you want to keep that historical perspective, or did more modern historical events affect how you portrayed the world?

If there was one thing I saw again and again while writing and researching this book, it’s that our contemporary authoritarian movements are uncannily similar to those of the thirties and forties, and I don’t believe that’s a coincidence. We have Steve Bannon citing Lenin as an influence, and the many examples of figures on the far right citing Hitler and Mussolini. So I spent a lot of time researching the totalitarianism of Orwell’s time, but the most important thing I learned is that it’s very hard to draw a distinction between the authoritarianism of past and present.

I was surprised that the book continued on (a bit) after what was depicted at the end of 1984.

My book needed to offer something new. It couldn’t have the same ending as Orwell’s book, and it couldn’t make the exact same political points. So I worked very hard to try to make it consistent philosophically with Orwell, but the plot had to offer surprises.

Did any dystopian novels of more recent times influence you?

To a certain degree, yes. That was a difficult line to walk. Generally speaking, contemporary dystopias have a very different logic from 1984. The Hunger Games isn’t a political warning, it’s a hero narrative. Most recent dystopias are the same. They’re about good people overthrowing an evil government or surviving in a post-apocalyptic world through their courage and decency. Along the way, they conquer their own demons. Sometimes there’s an unhappy ending, but the people are still behaving heroically.

There’s nothing wrong with that, and a lot of writers have done smart things with it, but it’s very much not Orwell. He made Winston about as unpalatable and unheroic as it’s possible to be. At one point, after a bombing, he casually kicks a child’s severed hand out of his path — and he does not look around to see if the child is nearby and might be helped. He fantasizes about murdering women on three separate occasions. He’s frightened of his own shadow, he’s infatuated with the brutal O’Brien and he’s wrong about almost everything. Orwell also makes a point of making him physically unattractive. It’s just a different kind of book.

So I did make Julia a bit more heroic than Winston, and I used more of the tools of a hero narrative than Orwell did, but at the same time, she isn’t Katniss Everdeen. She’s much more of a creature of her tainted world.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.