When was the last time you saw live music? It doesn’t matter if it was an arena show or an experimental artist in a tiny venue; what matters is that you were there taking it all in. It isn’t all that strange to see less live music as you get older: work and family can mean less time or money for tickets, and the artists that you loved seeing at 25 might not be doing as much touring 10 or 20 years later.

Still, there are plenty of reasons to keep live music in your life, from the sheer enjoyment of the experience to research suggesting that live music is good for your health. In his new book Live!: Why We Go Out, longtime BBC Radio host Robert Elms makes a very compelling argument for why going to see live music is eminently worth it as a lifelong pursuit.

InsideHook spoke with Elms about his own experiences with live music, his favorite London venues and what the future of concerts might look like.

InsideHook: The book opens with you talking about going to see live music in the aftermath of the pandemic. When did the idea to write this book looking back on your history of concert-going first come to you?

Robert Elms: It was very much during the pandemic. I think it was one of those instances where you only know what you miss when it’s gone. And because there was no live music for 18 months, or however long it was that live music was illegal. I mean, to think about that is kind of crazy. After a while, I just realized that it was probably the thing I missed most. I could still kind of talk to my friends. My family was there. It wasn’t hard for me; I didn’t get sick. But I really, really missed going to gigs, gigs and games. Football and sport, as you see in the book, I see them as analogous. Live music in particular, it really hit home to me that I’ve done this since I was 15 pretty much every week. And suddenly I couldn’t do it. That’s when the idea for the book came along, really.

Was it difficult to think back on experiences that were several decades old, or were you looking back on anything to recall those experiences with more detail?

I had nothing to go on. I’m not a keeper of memorabilia. I don’t have ticket stubs. I don’t have any of those. But as I say in the book, I have a slightly odd memory. I have a very vivid memory, but only of one moment of each gig. I say I have a photographic memory, but it only takes Polaroids.

I think I’ve been to somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 gigs, I think if I were to add it all up, but I can summon them. I can summon a moment from almost all of them — or, say, the good ones. When you start trying to remember, memory unlocks other memories. So you go back to that gig and then you remember, “Oh, and then I saw them again there, and the support act was…” Writing the book unlocked the rooms of memory, if you like.

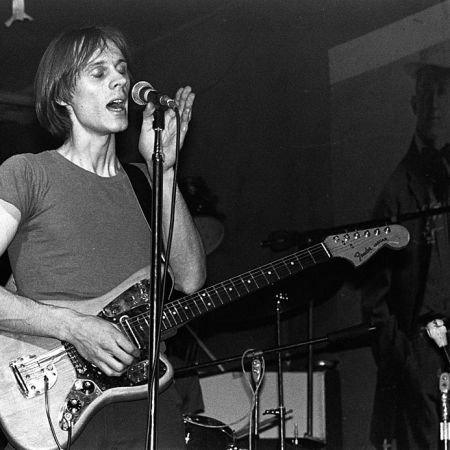

I really enjoyed the way that you talk about the evolution of sort of seeing The Clash in bigger and bigger venues, and then watching the evolution of the band.

Well, in terms of bands, if I could go back to any moment, it would be being 17 and watching The Clash again. I’m not a religious man or a spiritual man, but that’s about as close as I’ve ever got to having a faith. You know, I believed in this thing, and it was changing my world. And it was making me see the world in a different way. I think that’s why I say that the most potent gigs are the ones that you see when you’re very young. Because that’s when you’re looking for your worldviews and all of that, and The Clash were mine. And it so happened that they came from the streets I grew up on, all of that stuff. And so those Clash gigs and watching The Clash were important, but also that process of feeling like they’ve let you down, they’ve sold out. That’s all part of the same process of growing up, I think.

As someone who has seen a lot of bands, I’ve had similar experiences where a venue is a little bit too large of a room for me to kind of click with it in the same way that I might have earlier.

With The Clash, I had that moment again, years later in New York when I saw them at Bonds, and I went not expecting very much. And they were magnificent. And I realized that our falling out, it had been as much my fault as theirs, if you know what I mean.

There are a lot of people for whom going to see live music is something that they do early in life, and then they stop. And one of the things that I really enjoyed about your book is the fact that you’re talking about still going to DIY spaces, even when you’re significantly older than some of the other people in the space.

Three times the age, these days. I mean, literally — I’m in my 60s and these are kids in their 20s.

What is it that keeps you going back? Do you find it frustrating that some people out of their 20s are have an attitude that going to see live music is something they used to, but not anymore?

That’s an attitude I don’t understand. I mean, first of all, I’ve been very lucky, because I’ve managed to make my career out of writing, radio and music. And so I’ve never lost touch, if you like. I think what happens with a lot of people is there comes a time when they lose touch, work becomes more important, family becomes more important or you haven’t got the money. I’ve been very lucky that that never happened. I never severed the cord, if you like, because my work enabled me to continue doing it — in fact, it encouraged me to continue doing it!

I think that’s important. Because if you get out of the routine or the habit of doing something, it’s harder to start doing it again. Also, I do go to different sorts of gigs. Now, it’s become jazz much more. I like to sit down when I can, because the knees aren’t what they were. But I still get a real thrill out of live music. And I get a real thrill out of the communality of it. It doesn’t work for me online. I’ve got to be there. And so I think I’m lucky.

And also, I do think that my generation, I was lucky when I was born. My generation, when we were kids, we were seeing the Clash and the Sex Pistols and the Crusaders and Bob Marley and whoever. If you saw something that was that good, it should sustain you and keep you wanting to do it.

One of the things that you return to again that resonated with me a lot — especially post-pandemic — was the stratification where it’s easy to go to a DIY show. But if you want to go see a larger touring band, it’s gotten much, much, much more expensive than it was before.

I think that’s a real sadness and a real danger. I think young people are being priced out of the market. My kids don’t go to gigs very often because they can’t afford to. And because they’ve never got in the habit, they don’t go regularly. And I think that, you know, of course, the money was different then. But, for 50 pence, like, you know, 50 cents, I could go and see the Clash, Elvis Costello, Ian Dury, The Jam, all in one week. And this wasn’t when they were unheard of. But that just doesn’t happen anymore. You know, you’re not going to go and see a band of any stature in London now for under 30 pounds. And my kids can’t do that.

I think there’s a real pressure on bands to play bigger and bigger venues rather than playing a lot of gigs. One could choose to play five nights in a smaller venue, or two nights in a bigger venue. Well, for me, they should they should choose the five nights in a smaller venue, because that means there’s more people, it’s more of an atmosphere, you’re closer, you feel more involved. I don’t enjoy going to big domes and stadiums. It just doesn’t do it for me.

I feel about the same way. I’ve been seeing live music for decades now. I think I can count on both hands the number of times I’ve gone to a stadium.

Also, the kind of event that people have to put on at stadiums is not for me. I don’t want to go and see firework displays and teams of dancers and huge screens.

You also wrote about your fondness for QPR and the experience of going to a match. Where do you see the similarities and the differences between music and sports?

Queens Park Rangers, I don’t know if you know, they’re a very second division English club. I don’t support Arsenal or Man United or Liverpool. And I think that’s kind of similar, the stadium only holds 15,000. It’s very close by, it’s still affordable, all that stuff. It’s still very community-based. The difference is that I go and watch Queens Park Rangers not really to be entertained, if that makes any sense. I go out of duty and fealty and loyalty.

Also, I’d rather they won in a bad, unentertaining game than lost in an entertaining one. So it’s different. It’s tribal. But what is similar is — I went to a Paul Weller gig about two weeks ago. And going to see Paul Weller was closer in some ways to going to see a sporting event. Because the crowd is very partisan. And they’ve been following him for a long time. And they know every word of every number. I like that shared sense that we’re all in it together.

You know, I first saw The Jam in 1975. And I watched Paul Weller last week, or whatever it was. So I like that. I like bands where that happens. Yeah, you’ve got a sense of being in this together. In all of the events, it is the communality. It’s the shared experience.

One of the things that you go into in the book is the way that your tastes have expanded, and how you’ve discovered different genres of music from traveling around the world and expanding your tastes. I feel like there is a kind of aesthetic conservatism that comes with a lot of people’s taste in music where some listeners don’t go outside of their comfort zone.

I think I was very lucky because I grew up in inner London. So that helped, right? Because I’m in a big city with lots of music everywhere. And all types of music. It’s a multicultural city. So you’d hear Jamaican music, Irish music, Greek music. The kids at school came from those places; when you went ’round the houses, that’s what you heard. So from very early on, I was used to a broad palette of music.

From very early on, at the same time, I was watching the Clash and the Sex Pistols. I was watching the Crusaders and Lonnie Liston Smith and jazz. And I think liking jazz from early on is quite an education, because jazz is going to challenge you every time you go and see it. It’s going to push you further out, or it’s going to do something you don’t expect.

From very early on, I was always into hearing new things and different things. There’s stuff I didn’t like and still don’t like. I’ve never got heavy rock, it just isn’t my thing. I’ve never gotten opera, which I think is rather similar to heavy rock. They’re both quite bombastic. I’ve always preferred music which is a bit more intimate and emotional.

I still have to challenge things. I thought I didn’t like country music at all. And I was convinced I didn’t like country music, probably until I was in my 50s. Maybe as you get older, you get a bit more sentimental. But also, I realized that my mum had liked this stuff when I was young. And of course, you didn’t like it because your mum liked it. But actually, I knew these songs. And I realized this.

The other thing is, I was also a travel writer for quite a number of years. And the thing about being a travel writer is you’ve got to arrive in a place with no prejudices. You don’t know if you’re going to like Bratislava or Ethiopia or Colombia or wherever. And so one of the things I always did when I traveled was that I sought out the local music, because eating the local food and hearing the local music were the two best ways that I could get to know a culture. So I discovered son in Cuba and flamenco in Spain and tango in Argentina. I’ve always made myself open to different styles of music.

I quite enjoyed your descriptions of seeing Gillian Welch and David Rawlings. I had the chance to see David Rawlings shortly before the pandemic, and the set was so good.

He’s amazing. I used to say that I don’t like guitar solos. And then I saw David Rawlings, and his solo on “Revelator” is still one of the greatest things I’ve ever seen. It’s angular and it’s elegant and it’s beautiful and it’s all of that stuff. That was another example of me challenging myself. I still don’t like “Smoke on the Water” or Led Zeppelin very much, but I can really enjoy David Rawlings.

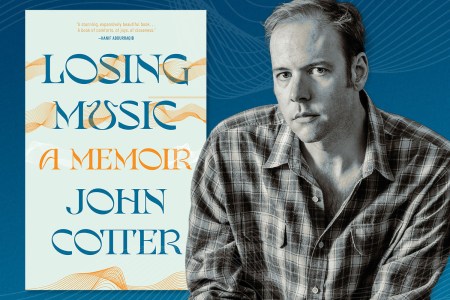

John Cotter Describes a Visit to the Mayo Clinic in This Excerpt From His Memoir “Losing Music”

The new book chronicles his efforts to understand and live with the mysterious Ménière’s diseaseAre there certain venues nowadays that you find yourself going back to where you really enjoy seeing live music?

There’s a jazz club in London called Ronnie Scott’s which has been there since 1959. And it’s had everybody. Miles Davis played there, and the whole litany of people. There’s a seat by the bar there that if you put me there every night of the week with a glass of red wine, I’d be a very happy man. But I also like going to see young bands as well.

There’s a whole series of pubs in London. There was a place with the Total Refreshment Centre, which is where a lot of the young British jazz scene was coming through. It was a room with no windows behind a carwash and a kebab shop in a really rough part of town. I loved going there. It was great. So those are the kinds of places I enjoy. Also some of the bigger ones, but nothing that holds more than a couple of thousand people, really. There’s an optimum size, I think, for me. Yeah. And nothing outdoors. That’s another thing I say: music doesn’t work for me in the daytime or outdoors. It just doesn’t.

Do you see there being a point where there might be a return to a more affordable, egalitarian way of going to see live music?

I’m an optimist about almost everything. And I think there will surely be a generation of musicians who will say, “We’re not in this for the money. We’re in this to make the music.” And I think there always is. And there always has been. There are bands who will do that. But I think the problem we’ve got is, like everything else, the digitization of music, for me, is not a good thing. I don’t want to watch music on a little screen. I don’t want to watch it on a computer. I don’t. And a lot of the music we’ve got at the moment is made for that sort of format. You know, a lot of pop music is designed to look like that. And therefore, when you go and see it live, you’re watching it on a screen rather than really on the stage.

The more music is kind of rootsy, whatever those roots are, the more it lends itself to the little backroom in a pub. You know, whether it’s folk music or country music or rock music or reggae or whatever, if it’s rootsy — and most of the music I like is music that has its roots on show, a bit like my hair. That lends itself to smaller venues, a more honest kind of music making, I think.

Is there anyone you’ve seen recently that’s really impressed you?

There’s a young musician who I mentioned at the very end of the book. I’ve known him since he was born, literally. His father’s one of my best friends, and he’s in a young band, and they played a gig the other night in Soho. They weren’t top of the bill, but there was another band ahead of them called the Molotovs, who were, like, 17. They clearly swallowed The Jam and The Clash songbook. And yet they sounded very now.

There were about 200 people in the room. Some of them were my age, but most of them were kids, but no one seemed to care. They didn’t make us feel out of place for being there. And it was just life-affirming. The music had energy and passion. And no one was making any money. It was just one of those nights. It was great. And I came out there with a massive smile on my face. No one was a Joe Strummer yet. But there was all the energy and all the joy and all the pain and angst and all those things were there. Yeah. And those are the ingredients that I need, really, from live music.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.