Conventional wisdom suggests that a nickname isn’t something you should give yourself. That rule doesn’t apply if you’re Ernest Hemingway, however, who started going by “Papa” sometime during his Paris years in the 1920s. By most accounts, the best-known of Hemingway’s slew of nicknames was a self-appointed one, which he is thought to have begun using around the age of 27.

Unlike most self-appointed nicknames, “Papa” stuck. Immortalized in A.E. Hotchner’s seminal Hemingway memoir, Papa Hemingway, the name has also graced the title of a subsequent memoir penned by one of “Papa’s” actual sons, and more recently the 2015 biopic Papa: Hemingway in Cuba. Journalists and literary scholars are still prone to pepper their writings on the novelist with the paternal pet name, and in other corners of the internet the nickname is offered as a fun bit of Hemingway trivia in online study guides or debated in question forums.

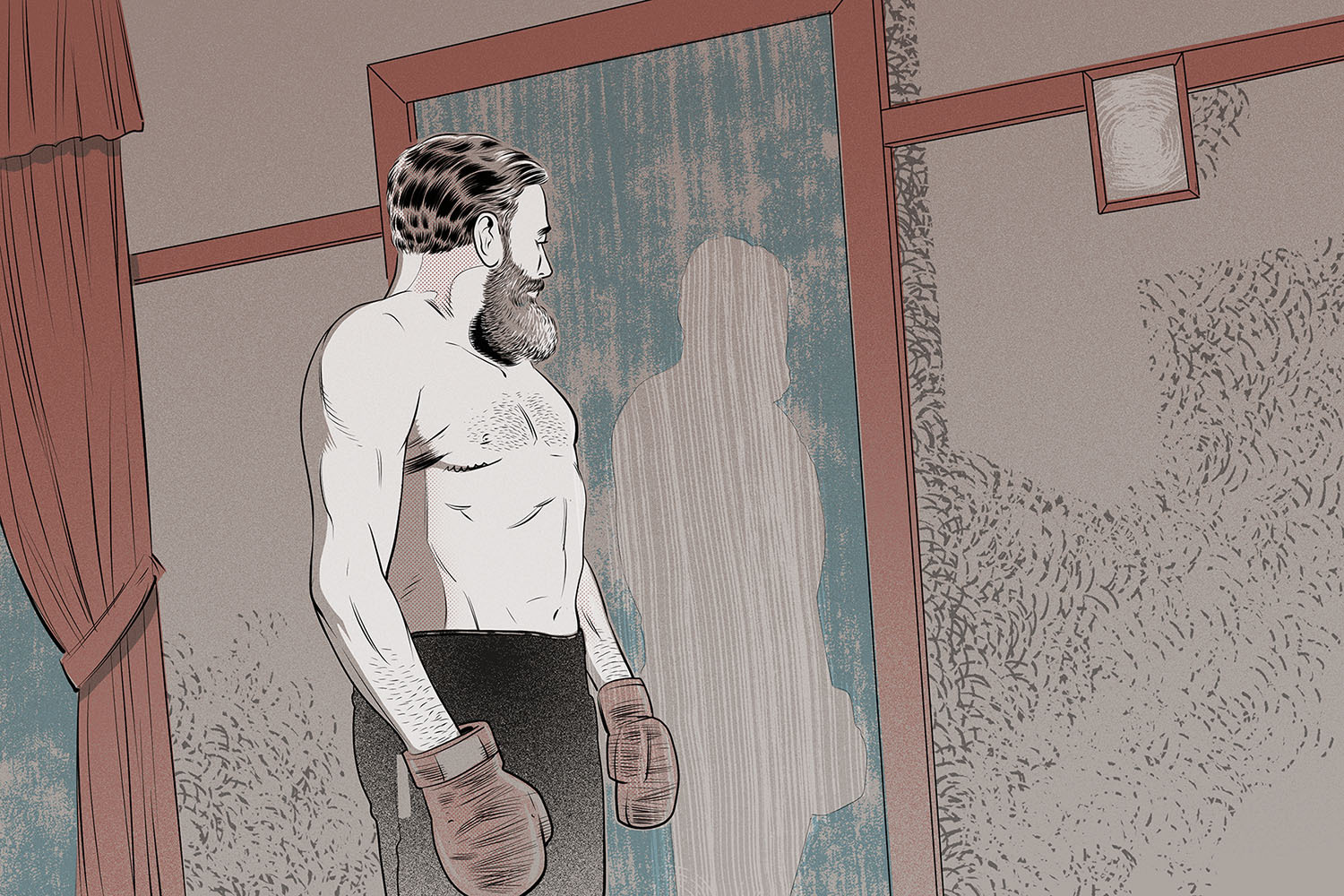

The moniker has far outlived the writer, and with it so has the overtly macho Hemingway persona it seems to reflect. Decades after his death, Papa Hemingway still looms large as literature’s patriarchal overlord, a daiquiri-swilling writer who became a monolith to a certain brand of aggressive virility because he wrote about war and bullfighting, had several wives and slaughtered big game on an African safari. He is a paragon of extreme machismo, with self-appointed nickname “Papa” to prove it. All this despite the fact that critics, scholars and biographers have been poking holes in Papa’s man’s-man legacy for decades.

A Farewell to Toxic Masculinity

Mainstream cultural conversation these days has generally soured on the particular brand of masculinity for which Hemingway is remembered. After all, “masculinity” itself is a word seldom heard these days in absence of the preceding qualifier “toxic.” But interest in Hemingway had already begun to decline as early as the 1970s, which Aaron Latham, writing for the New York Times in 1977, attributed to the shifting sexual mores of a more progressive era beginning to distance itself from a fixed and binary conception of gender.

“One reason for his sagging reputation may well be his exaggerated masculinity,” wrote Latham. “All those pictures of him exhibiting his manhood — hunting, fishing, killing, going to war, boxing — appear to have yellowed in our memory. Papa seems to offend this age when men are recognizing their ‘feminine’ qualities and women are admitting certain ‘masculine’ characteristics.”

Essentially, as the world began to rethink ideals of masculinity, Hemingway’s once-revered brand of it suddenly seemed hyperbolic and distasteful, a heavy-handed monument to a bygone era of manliness.

Latham’s hope was that the author’s image, which had by then “dwindled into a self‐caricature,” could be rehabilitated for a new generation of readers by the recently surfaced body of his unfinished works, which seemed to reveal a different, more androgynous Hemingway than the public-facing Papa persona, one who was fascinated with gender fluidity and penned tales of gender-bending romance that suddenly magnified queer undertones in some of his best known works.

Among them was a then-unpublished novel called The Garden of Eden, which, as Latham put it, “seems to recognize sexual relativity.” The novel was eventually published, albeit in a much abbreviated and controversially edited form, in 1986, and tells an unexpected story of gender bending and sexual experimentation between a young married couple honeymooning in the south of France — where Hemingway and his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, had honeymooned in 1927.

In the novel, successful young novelist/Hemingway stand-in David Bourne and his new wife Catherine experiment with sexual role-reversal. Within the first chapter, Catherine cuts her hair short, telling David she asked the barber to give her a haircut identical to her husband’s. “I’m a girl, but now I’m a boy too,” she tells David, who begins calling her “brother.” That night in bed, Catherine takes the lead in a vaguely veiled sex act she later says they wouldn’t be able to do in Spain — “such a formal country.” She tells her husband not to call her “girl” and begins to call him “Catherine,” insisting that he call her “Peter.”

“You are changing,” she tells David during sex. “Yes you are and you’re my girl Catherine. Will you change and be my girl and let me take you?”

This posthumous foray into sexual fluidity may strike some Papa Hemingway disciples as uncharacteristic of the author, but critics and scholars were quick to point out unmistakable similarities between the Garden of Eden and one of Hemingway’s best known earlier works, A Farewell to Arms. In the latter novel, the female lead, also named Catherine, sets the stage for many of her nominal predecessor’s sexual experiments, from her fantasy of tonsorial twinning with her male lover to the sexual subversion that Debra A. Moddelmog’s reading finds in the couple’s premarital, woman-on-top sex — which, while tame by today’s mores, was enough to get the book banned in Boston in 1929. Throughout The Garden of Eden, Catherine Bourne consistently and sometimes eerily echoes the earlier Catherine’s desires and fantasies, magnifying the queer sensibilities that went largely overlooked in Hemingway’s earlier work.

Queering Hemingway

In addition to the suddenly glaring similarities between Hemingway’s newfound tale of queer eroticism and the masterpieces he published during his lifetime, scholars and biographers have also noted certain parallels between the sexually fluid experimentation in The Garden of Eden and Hemingway’s own life. As Carl P. Eby notes in his reading of jealousy and destruction in the novel, “Papa” wasn’t the only nickname the author gave himself: “When Hemingway dyed his hair red in 1947 and shaved his head in Africa in 1953, he called himself ‘Catherine.’”

Twenty years after he became Papa, Hemingway, like David Bourne, became “Catherine,” suggesting that the ultra-masculine persona for which the author is best remembered was one of possibly many performed alter-egos he tried on throughout his life. Indeed, Eby goes as far as to offer a biographical reading of The Garden of Eden arguing that “both David and Catherine are, of course, reflections of Hemingway’s imagination and different aspects of his psyche,” presenting Catherine as “Hemingway’s split-off other-sex alter-ego.”

Speculation about the potential fallibility of Hemingway’s relentlessly macho aesthetic was afoot well before his revealing unpublished works were made widely available. By the 1970s, as Latham noted, the predominant question surrounding Hemingway’s masculinity had already ceased to be one of, “Do I measure up to Hemingway’s standards of manliness?” in favor of “Was Hemingway overcompensating for some sexual ambiguity?”

By the time The Garden of Eden was published in 1986, that “sexual ambiguity” — or at least Hemingway’s interest in exploring it in his work — was common knowledge in most literary circles, with Nancy Comley and Robert Scholes officially declaring Papa Hemingway dead in 1994. “The Hemingway you were taught about in high school is dead,” they wrote in Hemingway’s Genders. “Viva el nuevo Hemingway.”

And yet, two decades and change later, the Papa Hemingway persona remains largely inextricable from the author’s public-facing legacy.

The Ernest Hemingway Collection, an online retailer apparently in the still-viable business of hawking Hemingway merch, promotes the author as a daring he-man whose accomplishments include being wounded in WWI, tracking game through the African bush, fishing the Gulf Stream and surviving two plane crashes.

For many fans and critics alike, Papa Hemingway remains the great-granddaddy of American modernism, the man who so fully embodies patriarchy at its most cartoonish extreme that he devoted a notable subsection of his memoir to penis size — namely that of contemporary and sometimes frenemy F. Scott Fitzgerald. Among literature’s most prominent embodiments of toxic masculinity, Hemingway tends to find himself among a certain cohort of white male writers that white male readers are often criticized for reading exclusively. “That famous John Waters quote that goes, ‘If you go home with somebody, and they don’t have books, don’t fuck ’em!’ should be revised to say ‘books written by people other than Hemingway, Kerouac, and Bukowski,’” advised a 2017 Cosmopolitan article.

For all the decades of scholarship that have tried to paint a more nuanced portrait of Hemingway, the author seems to remain, as Time magazine noted in 1999, forever “trapped in his own latter-day legend as ‘Papa.’”

The Garden of Eden, which Hemingway began to write in 1946 and worked on intermittently throughout the rest of his life, is not a carefree tale of happy honeymooners. Throughout the novel, David Bourne wrestles with his wife’s sexual desires, finding that while Catherine “changes from a girl into a boy and back to a girl carelessly and happily,” he can’t shift as comfortably.

As their marriage continues to deteriorate, David takes an interest in Marita, a woman who seems content with assuming a more traditionally feminine role, and he and Catherine repeatedly fight over “the clippings,” aka glowing reviews of David’s book that seem to present him as someone Catherine finds jarring and unfamiliar from the husband she calls by her own name in bed at night.

“I’m frightened by them and all the things they say,” she tells David. “How can we be us and have the things we have and do what we do and you be this that’s in the clippings?”

If we accept Eby’s reading of Catherine as Hemingway’s own “split-off other-sex alter-ego,” then her distress over the clippings seems to hint at an internal strife between Hemingway’s own public and private selves. Was he the Papa of the clippings, the reviews, the great larger-than-life legacy? Or was he something else? Could he be both?

Decades after his death, it seems society has an answer to the latter question, at least. Years after our first glimpse of a more complicated, more nuanced, more fluid Hemingway, we still seem determined to only see the man from the clippings. We only see Papa, not Catherine.

“Hemingway, as novelist and public he‐man, still haunts our culture,” Latham wrote in 1977. “Ernest (Papa) Hemingway haunts our culture the way our own fathers haunt our individual lives.”

Four decades later, the open but ignored secrets of Hemingway’s inner life serve as a reminder of how little we ever really know our own fathers, and perhaps how little we really want to.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.