You couldn’t ask for a better cast of characters than the ones in Duncan White’s new book, Cold Warriors: Writers Who Waged the Literary Cold War. It features George Orwell, Richard Wright, Joan Didion, John le Carré, Mary McCarthy, Ernest Hemingway and many of the other literary luminaries who were on both sides of the escalating Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. Some, like Orwell and Hemingway, saw firsthand the horrors of warfare during the First World War and Spanish Civil War; others, like Russian writers Isaac Babel and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, were considered enemies of the state and imprisoned or (in Babel’s case) executed by Stalin’s regime.

And while he was nothing like a character out of one of le Carré’s books or the most famous British secret agent of them all, James Bond, the novelist Graham Greene tried his hand at the spy game.

Coming in at just under 700 pages, Cold Warriors is a bit of a doorstopper, but White shows he’s equally comfortable telling the stories as he is researching them. Every story is fascinating, but there was something about Greene — who did write some of the best novels about espionage and international mystery — and his attempts at getting into the spy game that really hooked us in. They sound like the plot of a Greene book, if we’re being honest. And it’s one of the reasons White’s book is easily one of the best literary history books you’ll read in 2019.

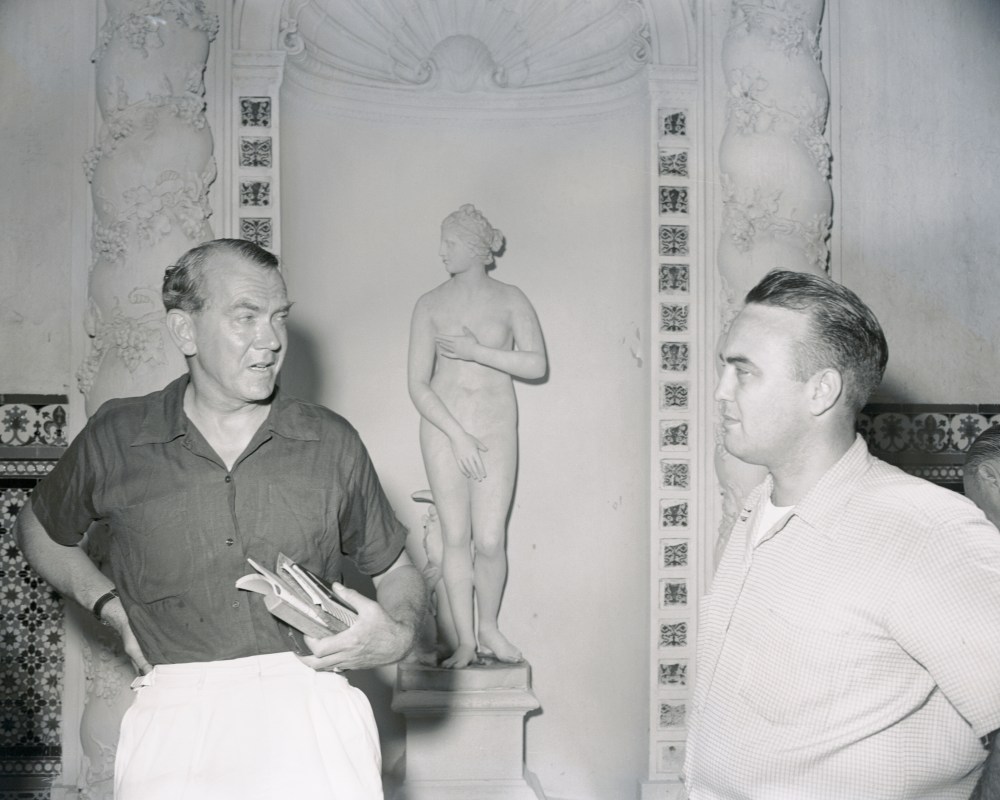

Graham Greene had a great idea for Kim Philby: a spy brothel. Greene had already identified “an admirable Madame” to run the place, which was to be set up in Bissau in Portuguese Guinea, where French Vichy officers stationed in Dakar “were apt to take holidays,” and Greene “felt that valuable information could be obtained from many of her visitors.” Of particular interest was the seaworthiness of the French battleship Richelieu, which had been damaged in holding off an Allied assault on Dakar in September 1940, and, if ready for combat, could do serious harm to British supply lines. Philby was amused by Agent 59200’s imaginative scheme. “For kicks, I put the plan to my superiors,” he wrote, “and we discussed it seriously before rejecting it as unlikely to be what is now called cost-effective.”

Greene was, of course, no stranger to inventing plots. At thirty-seven, he was a successful author, having published thrillers such as Stamboul Train (1932) and A Gun for Sale (1936), as well as more ambitious novels like Brighton Rock (1938) and The Power and the Glory (1940). He was also no stranger to brothels—in fact, he became something of an expert—and while he later referred to his scheme as “a rather wild plan,” he was disappointed when it was rejected. It was, he felt, one of his better proposals.

Freetown was not a frontline posting, but Greene’s clandestine work was consequential. Freetown was an important port on the route from southern Africa to Europe, and one of Greene’s most important responsibilities was to uncover illegal diamond smuggling coming through Angola, a colony of neutral Portugal (the Nazis needed diamonds, which were used in precision tooling, so stopping the supply was imperative). As such, he needed to keep an eye on suspected German agents in West African ports. There was also the prospect of a Vichy invasion from French Guinea, and Greene needed “to have agents near the border on the lookout for any possible movements by the French.” It was not exactly the stuff of James Bond—he did not have a gun and drove a second-hand Morris—but it was real intelligence work.

Spying was in the family. Greene’s uncle, Sir William Graham Greene, had been Permanent Secretary to the Board of the Admiralty and had been instrumental in setting up the Naval Intelligence department. Greene’s eldest brother, Herbert, was a less patriotic operator, having provided naval intelligence to the Japanese in the 1930s before working for another, mysterious benefactor during the Spanish Civil War. His youngest sister, Elisabeth, had joined SIS in 1938, working as secretary to Captain Cuthbert Bowlby, head of the Middle East Section. When Bowlby went out to run the Cairo station, Elisabeth went with him, meeting another SIS agent, Rodney Dennys, whom she would later marry. Dennys later became a script advisor for the Bond film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Elisabeth made the case for her brother to join the service, but despite her advocacy they wanted to vet him thoroughly, possibly because of his brief flirtation with the Communist Party back in 1925, or because of Herbert’s dubious activities.6 He was invited to a series of boozy parties hosted by a man called “Smith” at which SIS agents could get the measure of their potential recruit. He passed muster.

The service represented an exciting way for Greene to avoid enlisting while earning good money; in a letter to the poet John Betjeman he said he feared the prospect of the Pioneer Corps, “the haunt of middle-aged professional men like myself.” He had a family to support and fretted about how the war affected his income. In the months before the war began, he had rented a studio in Bloomsbury where, aided by Benzedrine tablets, he crashed out a commercial thriller, The Confidential Agent, in the morning, while working on the ambitious The Power and the Glory in the afternoons. He sent his wife, Vivien, and the two children to stay with his parents in Crowborough, East Sussex, where he hoped they would be safe from German bombs. This also cleared the way for him to continue an affair he was having with Dorothy Glover, his Bloomsbury landlord. He tried working for the Ministry of Information but found the work pettily bureaucratic, so he quit and became an air raid warden at night and the literary editor of the Spectator by day. The pressures of war demanded a greater contribution, though, and Greene knew he would not make much of a frontline soldier.

Related: How Hemingway Liberated the Ritz Hotel Bar From the Nazis

In August 1941, Greene wrote to his mother to tell her that he was going to Africa with the Colonial Service. Over the following months, he received training on a demanding course for Intelligence Corps officers at Oriel College, Oxford. He was not cut out for the rough-and-tumble stuff—the instructor gave up on teaching him how to ride a motorbike when he damaged two—but Greene was a keen student of his tradecraft, making copious notes in shorthand on how to recruit agents, how to intercept letters, and how best to maintain cover and avoid surveillance.

On December 9, he boarded a cargo ship in Liverpool with twelve other passengers and, after being drilled in watching for U-boats and using the fixed machine guns, they set out for Lagos, Nigeria. The journey was horrible. He was seasick, it was freezing cold on deck, and the prospect of a submarine attack filled him with dread; he wrote in his diary that “even a bird can look like a periscope.” His fears deepened when he found out that, along with depth charges used to deter sub attacks, the boat was carrying TNT in its cargo hold. To deal with it all he drank—heavily. On Christmas day, he awoke with such a terrible hangover that he promptly downed a bottle of champagne to help deal with it.

From the book, Cold Warriors: Writers Who Waged the Literary Cold War. Copyright ©2019 by Duncan White. Reprinted by permission of Custom House, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.