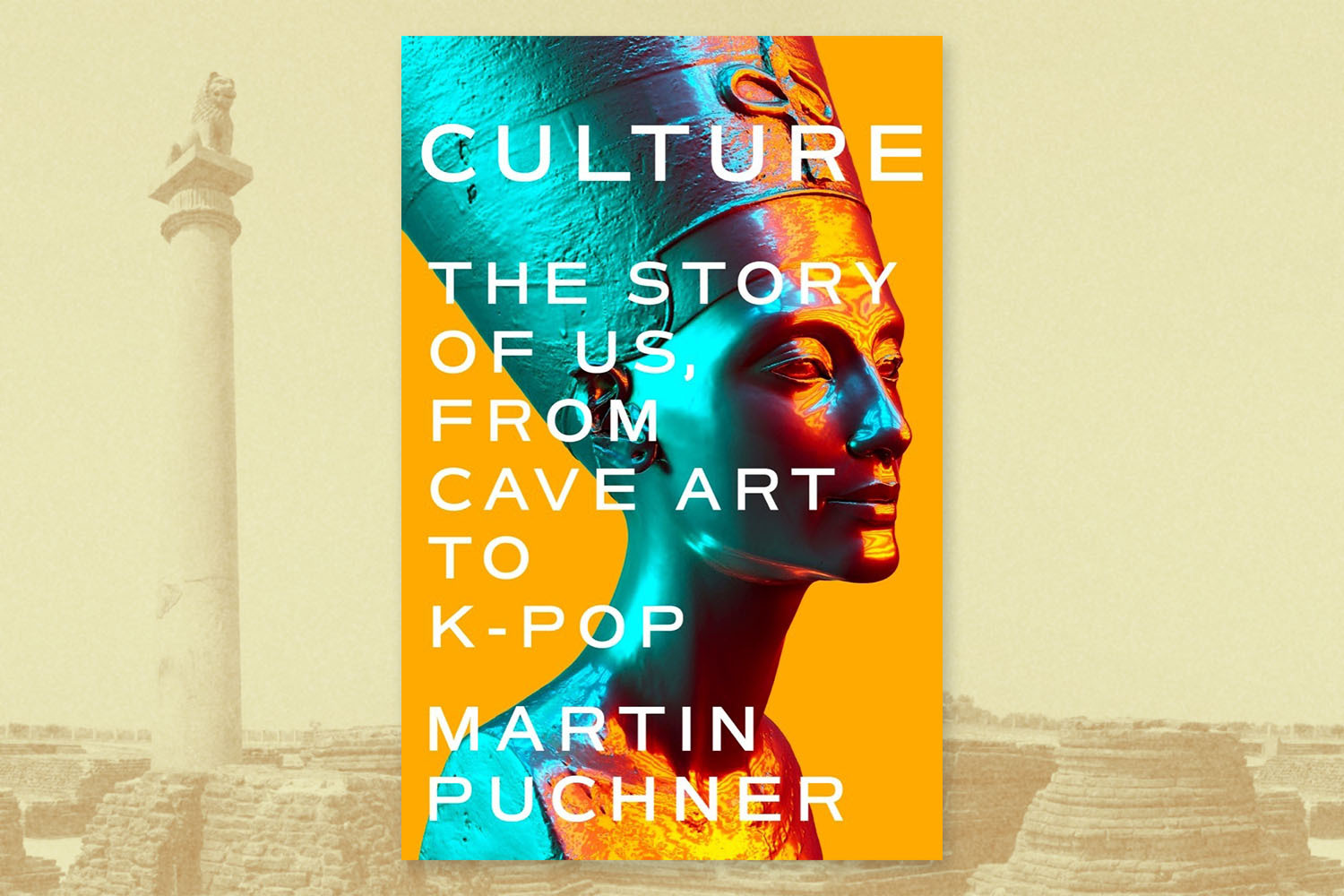

There are myriad challenges facing anyone writing a detailed work of history, whether it’s focusing on a single event or an extended period of time. For his new book, Culture: The Story of Us, from Cave Art to K-Pop, Harvard professor Martin Puchner opted to think big. His canvas includes tens of thousands of years, beginning with the first artists to create images on stone walls and taking the reader through to the present day.

It’s a wide-ranging, globe-spanning book that makes an enduring argument about culture, history and the interconnectedness of civilizations. Puchner memorably explores the way that different cultures overlapped over the years, contemplating everything from a South Asian artifact found in the ruins of Pompeii to Albrecht Dürer’s interest in Aztec art.

InsideHook spoke with Puchner about the making of his new book, the stories he uncovered while researching it and the importance of studying history.

InsideHook: In writing a book about culture across the entirety of human history, you’ve given yourself a huge amount of information to draw from. What were some of the challenges of working on a project with such a vast scope?

Martin Puchner: Yes, writing about culture on a scale of thousands of years is challenging, to put it mildly. Not only is there an almost infinite amount of information to draw on; there are also very few models to help you along the way. Most people stay away from this kind of project — for very good reasons.

But despite all of this, I have somehow managed to convince myself that there is no time scale that’s too large (or too small). It all depends on the kinds of questions you want to ask. And since I wanted to understand how culture works, the largest possible time scale seemed like the obvious one to choose to see what kind of patterns would emerge. Then, in a second step, I tried to pick episodes that illustrated the overarching story of culture, a story of cultural borrowing. This is how I ended up with the fifteen episodes.

You’ve written and edited extensively across a number of genres, languages, and styles. Going into Culture, how much of the history in it were things you were already aware of as opposed to things you discovered as part of your research?

It was a mixture. When I first stumbled into the job as editor of the Norton Anthology of World Literature about fifteen years ago, I spent a couple of years reading much more widely than I had ever done before and working with experts in all kinds of areas. That’s when I first came across texts that I found fascinating but which I had never heard of, such as the Great Hymn of the Aten, the Egyptian text that envisions an early form of monotheism, the Kebra Nagast, the Ethiopian scribal text written in Ge-ez, or the Lusiads by Camoes, the Portuguese sailor-writer who tried to capture the expanded sense of the world in the age of exploration. Also, there were some figures I knew from my earlier specialization in modernism, such as Ernest Fenollosa, who translated Japanese Noh theater into English, or the Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, who significantly shaped the way I think about culture.

But there were also figures I didn’t know well before, such as the Mauryan king Ashoka and his fascinating pillars, the Japanese traveler Ennin, or Aztec picture books. Nor did I know about the South Asian statue in Pompeii, even though I have been to Pompeii several times. Because I grew up in Nuremberg, Germany, I knew all about the city’s most famous painter, Albrecht Dürer, but I didn’t know that he was one of the first to encounter and write about Aztec art. So, in short, it was a mixture of figures I had long wanted to write about and many things I learned along the way.

Your earlier book The Written World focused on storytelling over the ages. Do you see this book as being in dialogue with that one?

Yes, The Written World was my first attempt at a “big-picture” book in the sense of asking overarching questions about culture.

Because I hugely enjoyed the process of writing The Written World, I decided to push this method a bit further and ask questions about culture, about why we produce it and how it works, questions I had never asked before because they somehow seemed too large to tackle. But they aren’t, really. Or at least, they’re too important to be left unanswered, so I decided to give it a try.

I think of Culture as a companion text to The Written World. The main themes from The Written World appear here and there in Culture but there is very little overlap.

At times, it can feel as though both culture and the study of culture are facing existential crises in this country from people who’d prefer to focus entirely on all things STEM. Do you see these things as being in conflict, or being more harmonious than some might believe?

Yes, I wrote this book in part before the background of declining enrollments in the humanities. Last year, only 8% of Harvard students expressed an interest in any of the arts and humanities subjects. That’s a breath-taking drop from ten, fifteen, twenty years ago, and it puts me and my colleagues in a position of having to make arguments about why culture is important. To make those arguments more effectively, I felt I needed to get a better sense of what culture actually is, and how it works.

The history of culture is interwoven with science and technology, since culture involves building techniques, printing and other tools all the way to our new electronic media. So, it would be wrong to think of the history of culture as somehow separate from STEM. At the same time, an important difference emerged for me, which I tried to express with the distinction between know-how and know-why. Know-how is the history of tools and scientific knowledge used to manipulate the natural world. Know-why, by contrast, the domain of the arts and humanities, is never directly useful in the same way. Instead, it deals with the way we humans make meaning, how we express our place in the universe. Even though those expressions, from cave art to K-pop, aren’t useful, we have spent an enormous number of resources to them. That’s what I tried to capture with this book: the history of humans as a culture-producing species.

How would you characterize the ways in which a layperson’s understanding of history in the U.S. might have changed over the last few decades?

All cultures fight over the past: it’s part of how we orient ourselves in the present. So, what is happening right now in the US is in many ways not unusual. If you look at school curricula, they have become more diverse and more global. But there is a backlash against that happening, whose current figurehead is Governor DeSantis, with his opposition to the AP course in African American Studies and his call for requiring courses in western civilization.

With Culture, I hope to give a deeper history to our current culture wars. I don’t think they will go away, and perhaps they shouldn’t go away, but I feel they could use more historical depth, a lot more historical depth. Our thinking about culture tends to be so short-term.

I’m not sure I’m really answering your question. I think of US history from an international perspective; debates here often feel quite parochial to me. So, that’s what I think I can provide, a more global history.

Was there anything in Culture that you’ve found yourself getting a significant amount of feedback for from people who were surprised to learn about something specific?

The book came out just a few days ago, so I’m sure I’ll learn more about how people react in the coming months and with different translations. But so far, my impression is that most readers know about some episodes well, but not about others. I launched the book a few weeks ago in India, at the Jaipur Literary Festival, and there, people of course know about Ashoka as well as the Portuguese voyages to India, but they didn’t know as much about the Kebra Nagast. A few days ago, I did an interview with the Shanghai Review of Books: there, people of course know about Xuanzang, the Chinese monk who went to India, and about Japanese missions to China, but they knew less about Aztec picture-books or the Haitian Revolution. It’s been extremely interesting to watch these kinds of international reception, and how readers from different cultures will approach the book differently.

As I’m describing this to you, it occurs to me that it is a specific instance of the larger theme of the book: different forms of cultural contact and mixing . . .

Were any of the historical periods within Culture especially challenging to research and process?

Different periods bring their specific challenges. The further back you go, the less information is available, and you are forced to extrapolate from tiny bits and pieces, as with cave art. here, it always amazes me how much one can extrapolate nonetheless, with educated guesses and detective work.

The more you move into the present, the more the opposite problem arises: an overwhelming amount of information. And a second problem: lack of perspective. I felt that the closer I moved to the present, the more I found myself getting drawn into very heated political debates. The purpose of the book was to give a deeper historical perspective to those debates, which is why most of the book emphasizes the remote past. But I didn’t want to escape these more charged debates, and hoped to contribute something to them with the larger story I was telling, hence the final chapters on colonialism, slave revolts, Western looting of non-Western art as well as the anti-colonial struggle and its aftermath.

My Conversation With Haruki Murakami Never Really Ends

Sean Wilsey chats with the prolific novelist about music, racism and a writing process that never stops evolvingA few years before the pandemic, you were a Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library. Did your time there inform the writing of Culture at all?

Being able to work for nine months in the New York Public Library, and in the company of fifteen scholars and writers was a fantastic experience. The book I wrote there, The Language of Thieves, was on a very different topic, a secret language of the road I had grown up with. It was part research, part family memoir. So that’s what I mostly focused on while at the NYPL. But the wide-ranging conversations during lunch, from art and dance to literature, and the presence of that grand library itself probably inspired me to write Culture. I had not thought about that before your question, but now that I think about it, I think you’re right. So, thank you, Cullman Center, all over again!

Were there any aspects of culture or scenes from history that you’d hoped to include in the book that didn’t make it in?

There are too many to count. Originally, I wanted to include a chapter on Persia and the Shahnameh, the book of kings, yet another text I originally encountered while working on the Norton Anthology of World Literature. I wanted to include a chapter on [the] Chinese scholar’s garden, where ideas of art and nature came together in unique ways, and which I encountered during my first trip to China fifteen years ago. I also wanted to include a chapter on Gertrude Stein and her art collection, but the previous chapter had inched its way toward modern art, so I felt there would have been too much overlap.

I am currently expanding Culture because I’m turning it into a textbook introduction to the arts and humanities, which will allow me to include some of these episodes that I had to leave out. As for the rest, there’s always the next book . . .

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.