“The people who talk about [Benjamin Sonnenberg] generally ignore his professional activities, which are somewhat arcane, and concentrate on his house and clothes, which are not,” writes Geoffrey Hellman in a 1950 New Yorker profile of Sonnenberg, who prefigured modern day Public Relations. The house, 19 Gramercy, had “five-stories and thirty-seven rooms,” was staffed by a cohort of servants befitting a Duke, and boasted an abundant collection of art and decorative furniture of museum caliber. Hellman called it “the busiest private house in New York,” hosting parties with rarefied society including playwrights, politicians and all manner of celebrity.

As for the man himself, Sonnenberg sported a walrus mustache and had his suits, all 67 of them, tailored to his specifications: “dark colors, four-button single-breasted coast, outside change pocket, no vest, double vent in back.” A Russian immigrant from modern-day Belarus, Sonnenberg earned his wealth in the early days of public relations — spinning personalities into brands and recognizing the ecosystem between media, celebrity and product — and seemed to derive more pleasure from his connections in high society than his high earnings.

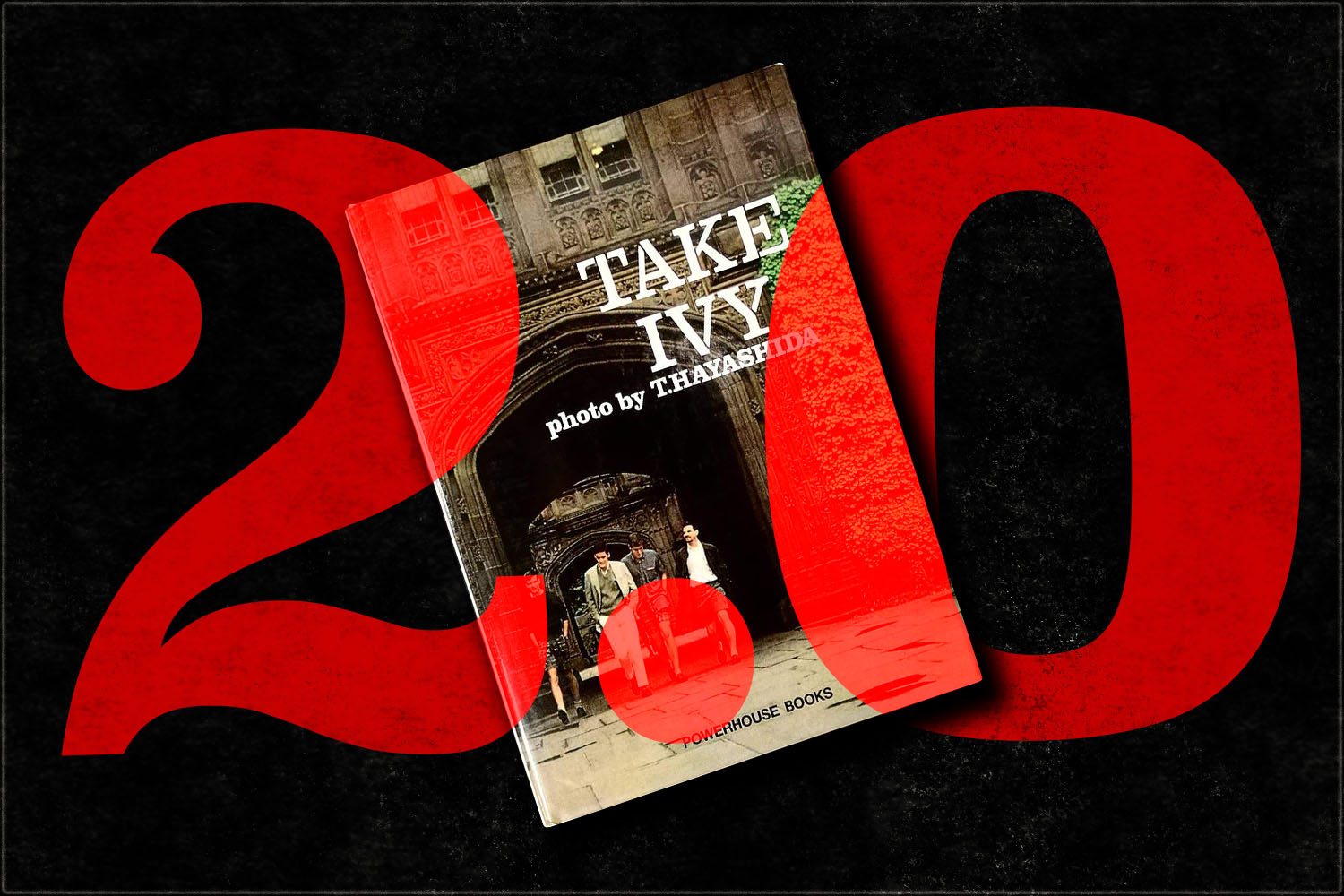

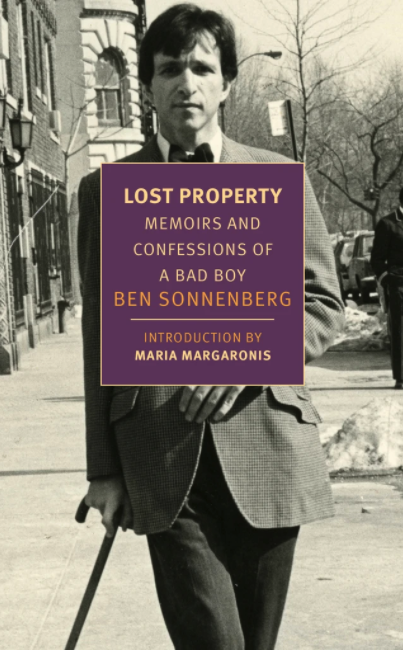

Nineteen Gramercy and Sonnenberg’s luxurious lifestyle are detailed in a memoir by his son, Ben, titled Lost Property: Memoirs and Confessions of a Bad Boy. In this wry, clever memoir, the younger Sonnenberg unabashedly chronicles a childhood of spoils coupled with an absence of familial affection, a psychological wound he salved with clothes, books and women.

Like his father, Ben too delighted in fashion and is what some might call a “dandy,” i.e., a man who dresses with scrupulous care. “Folly for me began with clothes,” writes Ben. “I thrilled to my first hand-made suit as much as to my new love affair.” Indeed, his enthusiasm is palpable when he dedicates whole paragraphs to his own memorable costumes, “I was wearing cream-colored corduroy trousers with wide wales, made for me by Huntsman, with a button fly; a green houndstooth-checked hacking jacket, also by Huntsman; a green Shetland sweater from W. Bill and a green-and-white gingham-checked shirt of cotton taffeta with my collar open and the tongue for the guide-button hanging out à la Douglas Macarthur. I was especially proud of my shoes.” And so on.

A dandy, according to Nathaniel Adams InsideHook contributor and author of I Am Dandy: The Return of the Elegant Gentleman, is “a man obsessed with personal elegance.” For Adams, dandyism is more than just a mode of fashion, it is a philosophical attitude. Always impeccably dressed, dandies are also high-minded contrarians that thrive at the convergence of society and culture and act aristocratic even when they’re not.

Ben’s socioeconomic background is typical of dandies and embodies what Adams terms “class revenge.” Dandies, Adams explains, are “usually upper-middle-class people who end up breaking into high society or rarefied cultural circles,” making up for blood lineage with intellectual prowess and refined taste. “They’re social lions,” Adams continues, “but they’re also observing from the sidelines in many ways.”

While the elder Sonnenberg could not escape the stigma of being Jewish and new money, Ben could not escape from under his father’s boot. Early in the memoir, Ben’s father’s presence is felt on nearly every page and, frequently, his pedantic voice interjects with a brusque parenthetical: “(‘Read A Raw Youth by Dostoevsky.’)” Sonnenberg rarely looked directly at Ben, for he was always reading.

Ben tried to buck his father by running exorbitant tabs across town—at tailors, Martini lunches, extended hotel stays — and forever prolonged his father’s decree for Ben to “increment” the allowance his father bestowed him.

Open this memoir to any page and the reader will find a bounty of proper nouns naming storied landmarks, bourgeois hotels and countless plays, novels and poems and their human counterparts. At times it can read like a social rolodex, casually name-dropping literary geniuses like Samuel Beckett, esteemed collectors like Peggy Guggenheim and, of course, designer brands such as Lanvin and tailors like Henry Poole.

This excess of capital letters, belied by real capital, exemplifies the task of a dandy to not only dress elegantly, but also to fastidiously cultivate one’s mind and social circles. Indeed, Ben learned to command the attention of his peers using his intellect and “domineering through taste in clothes and art” when he otherwise might have been slighted for his Jewish heritage.

As a socialite, Ben trafficked in gossip: gossip of literary scandal, of artists’ quibbles, of romantic trysts, of international espionage. His ear for gossip was so acute he even had a brief stint working for the CIA in Germany during the Cold War, something he agreed to more for the thrill than out of any sense of patriotic duty.

His politics, at times extreme, were forever non-committal. He was never serious in his political beliefs and expressed more passion toward social causes in Greece than in discrimination back home (mind you, this was around the time of the Civil Rights movement in the U.S.). While he held fast and hard opinions about art, music and literature, when it came to politics, he preferred to quote others or play devil’s advocate.

Contrarian politics is common for dandies. Deeply individualistic, dandies do not ascribe to any one political philosophy and share little in common other than bucking trends and refusing to associate with any particular “ism.” “People are shocked to find out how dandies were fascists or right-wing,” Adams told me, “but people are often not sure if dandies are just doing that to shock or [if] they really believe it.”

Within the culture of dandies, there is a subset of “literary dandies” who are as scrupulous with words as they are with fashion. Among their ranks fall Oscar Wilde, Mark Twain and Tom Wolfe, to name a few. When asked if there was any discernible connection between a dandy’s fashion sense and literary style, Adams concurred. “If you look at the way they dress and the way they write,” says Adams, speaking of Twain and Wolfe, “the two are often very sympathetic.”

Dandies are perhaps at the height of their powers when delivering clever quips. This could be seen in Ben’s precocious humor as a literary critic for The Nation. In his memoir, his cleverness shines brightest in self-deprecating jabs, especially when related to women. “She was indeed a pretty girl,” Ben wrote. “Her only flaw was she wasn’t prepared to be as interested in me as I was prepared to be interested in her.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.