There are more reasons to see the new movie The Green Knight than there are Knights of the Round Table: it’s helmed by buzzy director David Lowery (A Ghost Story, The Old Man & the Gun); it stars Dev Patel cutting a dashing figure as Sir Gawain; it’s being distributed by indie tastemaker A24 (Zola, Minari); it promises to revive the standing of the Arthurian epic, a genre that fell out of favor after Guy Ritchie’s King Arthur: Legend of the Sword disappointed in 2017; and the reviews so far are glowing, The Atlantic calling it one of the best movies of the year. And I could go on. But the best reason to see The Green Knight? Because J.R.R. Tolkien said so.

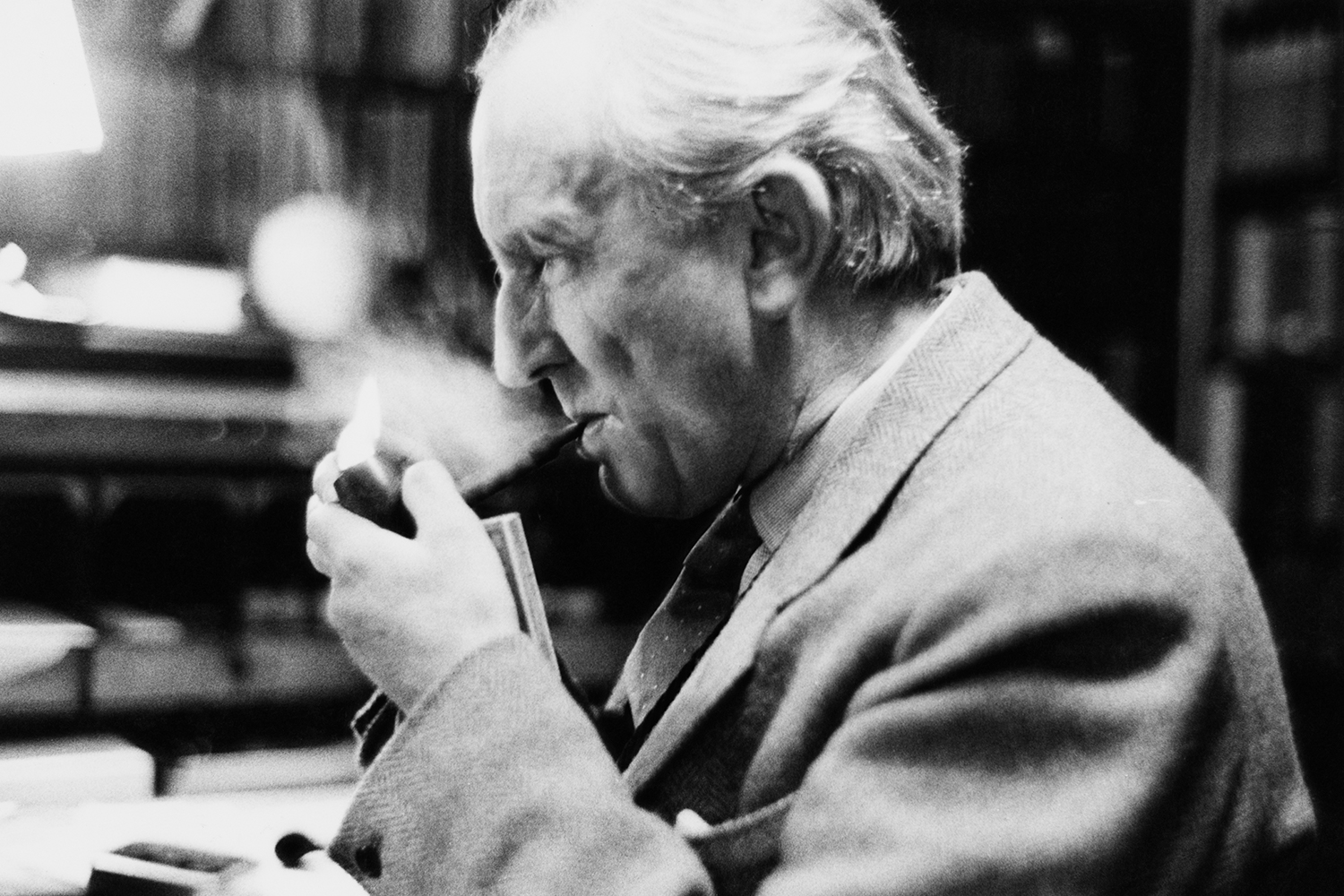

Before Tolkien dreamt up Middle-earth, published The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and took his rightful place as the king of modern fantasy, the Englishman was enchanted by a poem written in Middle English, what he called “one of the masterpieces of fourteenth-century art in England, and of English Literature as a whole”: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which serves as the inspiration for this new film.

In The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays, a posthumously published collection of Tolkien’s lectures, the author’s son Christopher, who edited the tome, describes Sir Gawain as “the poem to which [my father] devoted so much thought and study.” Indeed, the elder Tolkien revisited this specific Arthurian legend — which follows Gawain on a quest after taking up a grisly challenge from the monstrous Green Knight — many times throughout his life.

Not long after serving in World War I, and while working at the University of Leeds, he published a definitive edition of the poem with fellow scholar E.V. Gordon. Decades later he completed his own translation of the text, which was then broadcast by the BBC in dramatized form and so widely respected that you can likely find a copy of his take at your local bookstore today.

What was it about this specific story of King Arthur’s court that so entranced Tolkien? If it was enough to prove a lifelong obsession for the author — the one responsible for one of the best-selling book series of all time (not to mention one of the simultaneously highest-grossing and critically acclaimed film franchises) — it certainly must be worthy of our time, whether in cinematic or written form.

There are certainly some clues, found in his various lectures, essays and other writings. In the aforementioned collection edited by Christopher, a lecture from the University of Glasgow in April of 1953 has J.R.R. Tolkien comparing the story to Beowulf, another of his unknown-author obsessions, as well as “some of Shakespeare’s major plays, such as King Lear or Hamlet.”

“Behind our poem stalk the figures of elder myth, and through the lines are heard the echoes of ancient cults, beliefs and symbols remote from the consciousness of an educated moralist (but also a poet) of the late fourteenth century,” he said of Sir Gawain, according to the transcription. “His story is not about those old things, but it receives part of its life, its vividness, its tension from them. That is the way with the greater fairy-stories — of which this is one. There is indeed no better medium for moral teaching than the good fairy-story (by which I mean a real deep-rooted tale, told as a tale, and not a thinly disguised moral allegory).”

To me, that endorsement alone is a more compelling case for buying a ticket to The Green Knight (and picking up a written copy) than any trailer, however artful, A24 has cooked up.

In an ideal world, though, we’d be able to give Tolkien a ring and get the full story about how the Green Knight first came into his life and how it changed the course of his own writing. Since we can’t do that, we did the next best thing: got in touch with Verlyn Flieger, Professor Emerita in the Department of English at the University of Maryland, a longtime and leading Tolkien scholar, who was able to shed some light on why, exactly, people who care even the slightest bit about The Lord of the Rings should care about Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

InsideHook: Do you remember your first interaction with Sir Gawain and the Green Knight? When was it, what translation was it and what stuck out to you?

Verlyn Flieger: It was the first time I was in graduate school, back in the ‘50s (I didn’t finish then). I honestly don’t remember what translation we used, but given the time period, it was probably pretty conservative. The fashion then was to use “archaic” diction — doth and hath, etc., whereas now it’s to bring the poem as up to date as possible.

For you, what makes this tale compelling?

It’s funny, it’s bawdy, it’s got lots of sex, it’s both fantastic and realistic — real forests with imaginary beasts and real castles with mythological inhabitants. The Green Knight is an old, old vegetation god, but Arthur’s hall is rowdy and uproarious. The characters are believable, and the plot, which combines two well-known folk motifs — Temptation and The Beheading Game — is so cleverly managed that each motif is made contingent on the other. The poet was a genius.

Do we know why Tolkien was interested in the tale enough to translate it?

Like any educated man of his class, he would have been required to translate it while at school. It was a set text for an English literature curriculum. Aside from that, he thought it was a very great poem, and wanted to try his hand at putting it into his own words. He called it “one of the masterpieces of fourteenth-century art in England, and of English Literature as a whole.” He said, “it has deep roots in the past,” and “it was made of tales often told before.”

Where does Tolkien’s version sit in standing among the others? Are there any characteristics that differentiate his translation?

The later translation he made, published by his son Christopher, is scholarly without being pedantic. It keeps all of the wit and humor, but puts it into good, plain modern English, not attempting to “update” it, but to make it intelligible to an audience that doesn’t read Middle English.

Can you find any influence of Sir Gawain in Tolkien’s own writing?

In a very general sense, both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings have the same leavening of humor, the same realism mixed with fantasy, and the same deeply rooted moral sense. No particular character is modeled on Sir Gawain, but Tolkien’s Treebeard has some of the flavor of the Green Knight.

Can you give me a sense of how influential Arthurian legend was on Tolkien and his writing?

Tremendously influential. The idea of the quest, of sacrifice for a greater good, of the chosen king, of human frailty, of love and loyalty and betrayal are all areas where Arthurian legend colored Tolkien’s story.

On a personal note, do movie versions of the writing you have studied throughout your career (whether it’s an adaptation of Tolkien’s work or The Green Knight) hold any interest for you?

Not much.

Why not?

Because they’re movies. By that I mean that they are limited in ways that books are not. Movies are an altogether different art form, one with time constraints (the human behind can only take limited sitting-time) and different rules. Movies are photography, not narrative, so they rely on different effects and different conventions. Words, which are ambiguous and slippery, have more metaphoric and symbolic power than images, which are concrete and fixed. Movies rely on actors, who can be effective, but are limited by their own bodies (even with CGI and special effects) while the theatre in a reader’s head has a cast of thousands.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.