You’d probably expect the founder of High Times to have had a fascinating life. You’d probably expect the same thing from someone who worked as a drug smuggler in the heady 1970s, to say nothing of someone enmeshed in the radical underground press in the heyday of 1960s activism. As for someone who checks off all of those boxes — well, it’s not hard to see how their life story might make for interesting reading.

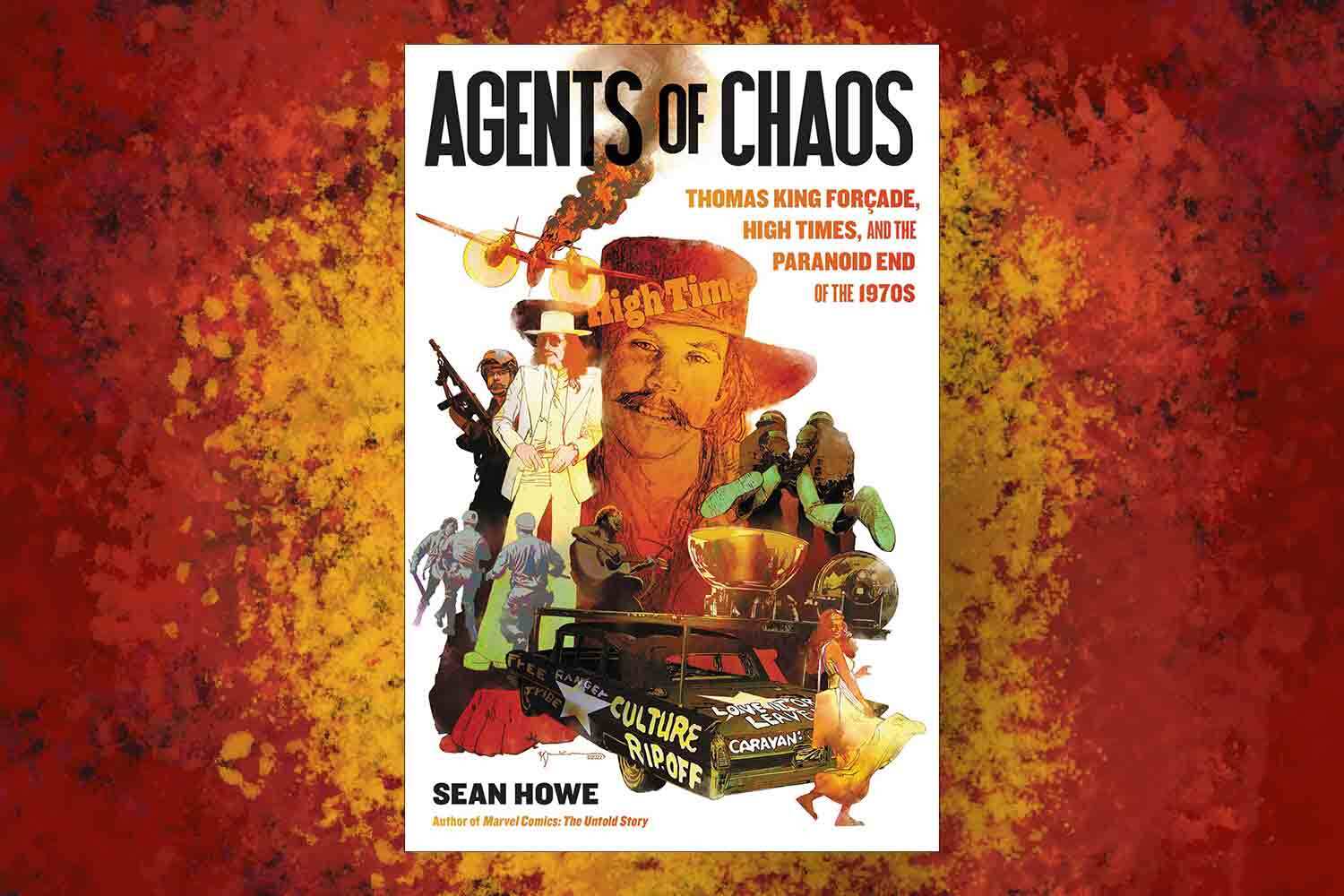

All of which brings us to Sean Howe’s fascinating new book Agents of Chaos: Thomas King Forçade, High Times, and the Paranoid End of the 1970s. Howe’s book introduces readers to Forçade when he arrived on the scene in the late 1960s, and left several journalists and activists with the suspicion that he might be a government agent. Howe’s book traces the complex life of a secretive man through First Amendment battles, the front lines of drug legalization efforts and a turbulent stretch in American history.

Howe’s previous book chronicled the similarly turbulent history of Marvel Comics. InsideHook spoke with him about the challenges of researching Agents of Chaos and the difficulty of writing about the life of someone who made a conscious effort to cover up plenty of details of his own origins.

InsideHook: The first I’d heard of Agents of Chaos was when you told me that you were working on it, and that conversation was long before the pandemic. When exactly did you start working on this project — and what was the first thing about this subject that pulled you into it?

Sean Howe: It began so long ago. The first time I heard or read the name Tom Forçade was late 2013. So it’s almost a decade. Essentially, I was shocked that I had never heard of someone who had been a part of so many different subcultures.

He was this guy who popped up in the drug smuggling world and the punk rock world and, obviously, the underground newspaper world. He was heavily involved in First Amendment battles. He was involved in radical politics and he basically had covered his tracks. So I was just astounded that this guy had popped up in so many places and so many worlds that I had an interest in and yet I’d never heard of him.

In the back of the book, there’s a long list of all of the people you spoke to in the course of researching it. How much of the information that you covered in the book was publicly accessible and how much of it did you have to dig for, whether it was looking into archival material or talking to people who knew Forçade or were in his orbit?

There were so many of all of those things. I will say there were a few people who had started to or attempted to write a book about him before me. One was Albert Goldman; probably the John Lennon biography is his best known work, or maybe the Elvis book. I think U2 helped really put his name out there for my generation.

Albert Goldman had known Forçade and there was a college era friend of his named Therese Ko who had done a lot of interviews. There were a couple of longer articles that I was able to see a little bit of. But other than a brief period in 1972, when Forçade was kind of chasing cameras, he really tried to keep his name out of everything and tried to pull strings in the background, which was itself compelling.

I found out that as early as 1969, he was showing up at gatherings of activists and people thought he was a cop. From almost the very beginning, there were claims that he was an agent provocateur. I think even in 2023, I think there are a lot of people interested in the idea, the possibility, that certain movements have had some kind of shadowy government involvement in the background. I guess there was probably a little bit of that that I thought maybe I could definitively uncover.

In the first section of Agents of Chaos, you feature a number of different people recalling Forçade and sharing their thoughts that he had to be an agent. And when you get to the truth of him, without giving too much away, the truth ends up being a lot stranger than that. When you were writing it, did you know from the outset that the structure of it was going to involve doubling back in time?

I went through a few different structural strategies. Originally I had this idea that I was going to start with a motorcycle accident that Forçade had in 1967, which I mentioned briefly. I had a perhaps pretentious or overly clever idea that I was going to pattern it on the opening of Lawrence of Arabia. I did actually talk to people who compared him to T.E. Lawrence, for various aspects of his personality and adventurism, but I decided I wanted to withhold a little bit more information about where he was in 1967.

I wanted readers to, as much as possible, experience Tom Forçade in the way that the people around him in 1969 would have, and to find out more about him at the same time as the investigative reporters who were digging into his identity in late 1972. That’s how some of the details about him, but only the barest details, came out.

I’m impressed that this is a book in which there are references to both Wyatt Earp and Jimmy Buffett.

Contemporaneous references too, yeah.

What was the biggest challenge of writing about someone who was so guarded about his past and seemingly was so guarded about his emotions?

He compartmentalized so much. And if you want to look at people who’ve traditionally been double agents, that is a common way to live that life. So even that just aroused more suspicion from me as I was working on it.

He had these groups of friends from different worlds who might consider themselves among his closest friends, but they didn’t know about the other groups. And in addition to that, he also tended to reset his relationships so that someone who knew him from 1968 to 1970 would then no longer have contact with him, or he would no longer have contact with them. There was a Rashomon quality in gathering impressions.

I spoke to his sister, I spoke to two women that he was married to, and yet there was something that was always elusive about him. I was able to find a lot of his writings. He was a very funny, very smart writer. And some of that stuff was reflective enough to seem truthful. But a lot of it like a photo negative image. There’s this sort of void that’s left.

At one point, you bring up a social event where Forçade was deemed to be “too outrageous” by Hunter S. Thompson, who assumably had a pretty high threshold for people being outrageous. It begs the question, what do you have to do that Hunter S. Thompson thinks, “No, that’s way too hardcore?”

Whether or not you want to label him as an agent provocateur, he was provoking at every turn. One of the core elements of his personality, I think, was his contrarianism. His political identity or his espoused political beliefs morphed a little bit, but I often thought of that Marx Brothers lyric, “whatever it is, I’m against it.”

And yet for all of this antagonism, I spoke to many people who thought he was like one of the greatest influences on their lives. People who truly loved him, people who saw very generous and tender aspects of him. And then on the other hand, there were people who hung up on me, as soon as I said his name.

It was really interesting to see the names of writers who crossed paths with Forçade earlier in their careers, like Ron Rosenbaum and Glenn O’Brien, who went on to become incredibly prominent in their fields. It gave the sense that he had solid instincts for who to work with.

He was one of those voracious readers where you think, “How is that humanly possible?” He just tore through newspapers and magazines every day. He was regularly reading everything from Guns and Ammo to women’s magazines of the seventies. Not feminist magazines, but new age-y, post-hippie women’s magazines.

Besides exploring Forçade’s life, Agents of Chaos also goes into a lot of history of underground magazines and newspapers in the late ’60s and early ’70s. How challenging was it to figure out how much of that to include and how much to leave out?

There are a number of, of really excellent books on the underground press. Smoking Typewriters by John McMillan is one. And there’s another book that just came out about the Underground Press Syndicate that’s focused on its treatment of marijuana, and is filled with great illustrations.

I have this perhaps unfortunate tendency where I like to retell stories as little as possible. I wanted to give the reader a pretty thorough understanding of it, but I guess I’m always afraid of repeating other people’s work. I feel like there should be a lot of value added. Sometimes that’s a challenge I don’t know that I need to give myself, but I wanted for someone who’s read books about the underground press to still feel like they’re learning about the underground press. But I didn’t want to make anything else seem redundant either.

Inside the Secret History of an American Literary Classic

Take a walk on the wild side of Louisa May Alcott’s groovy, gritty girlhood.Your previous book about Marvel Comics was dealing with some of the same time period as Agents of Chaos. Did you find any figures that ended up overlapping in those two worlds?

There were a lot of adjacencies. There were people in this book who knew people in the other book a lot. There were people in the Marvel book who were involved in the counterculture, but I don’t think there was anyone who knew Stan Lee and Tom Forçade. I was surprised at how many resonances there were between the two stories. One thing is that in neither of those books did I set out to tackle concepts of corporatism and capitalism. And that emerged; that ended up being big, big parts of both books.

Agents of Chaos details some very high-profile legal challenges that were made to smaller underground publications, and to be reading this at a time when local and regional newspapers are in the news for facing similar legal cases that could be financially ruinous to them felt like history was echoing 50 or 60 years apart.

I’m glad you brought that up. I’ve been paying attention to a lot of those stories and my wife asked if I’d seen one of the stories about a newspaper that was covered in the Times in the past week or so. It really echoed so much of the stuff that underground papers were dealing with in 1969, in terms of local government interference and trying to find a printer.

As much as High Times is an obviously huge legacy of Tom Forçade, the First Amendment stuff is really remarkable. His battle for press credentials for the White House, the case that he was part of, ended up being used as a precedent case for the CNN versus Trump lawsuit. I think even journalists who have never heard of Forçade might be affected by those decisions.

One of the things that really surprised me when reading this book was that I hadn’t realized how big of a movement marijuana decriminalization was in the late 1970s and the extent to which it seemed like the Carter administration was on board for that. Was there anything that surprised you as you were researching it? And there, too, how did you decide what to leave in and keep out?

I was compelled to leave everything in and to write twice as much, but reality stepped in. There are many reasons that this book took so long, but there were endless — I don’t want to say tangents — but so many aspects that I felt deserved its own book, but I didn’t know if anyone was going to write it. So I should bite off as much as I can.

I always had the challenge of remembering, well, this has to like come back to Tom Forçade; this is not an encyclopedia of counterculture in the 1970s. As much as the ’60s and ’70s have been rehashed in popular culture, I think that there’s so much that’s kind of left out of the usual narratives. One advantage of this mostly taking place in the 1970s is that I think a lot of people’s understanding of the 1970s goes from like Altamont and Kent State to stagflation, gas lines and Iran. There’s not a lot that illustrates how you get from point A to point B, and so I felt like there was a lot to fill in.

Regarding marijuana decriminalization, I didn’t know any of that stuff before I started working on the book. Some of that was pretty well-documented. And then there were aspects of it that were a little more buried, that required a little more digging.

Tom Forçade was very much a part of the progress that decriminalization and legalization made in the mid and late ’70s. But then High Times was kind of front and center for it collapsing.

Was there anything in terms of archival material that was a particular challenge for you to find or became a Holy Grail during the process of researching and writing this?

The Holy Grail in that I never found it were drug agency records about Forçade. My FOIA requests were sort of fruitless. I have FBI records that involved drug investigations, but there’s no record I could find from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs and then the DEA. The Secret Service is also copied on some of the FBI files and I could not access any Secret Service files on Forçade. Allegedly he had a plot to assassinate Nixon, and so you would think, well, the Secret Service should have something on this. That remains a little bit of a mystery to me.

His sister gave me access to a lot of his childhood and high school and college papers. I have copies of his college transcripts and I have papers he wrote in elementary school and that kind of stuff is pretty valuable for a psychological portrait of someone. The underground press is thankfully archived in microfilm and, in some cases, digitally. I did spend a lot of time, um, you know, looking at microfiche.

It’s been a long time since I last looked at microfiche. It gets a little dizzying after a while.

It does, but there’s so much history there that’s not anywhere else.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.