Can one article change the course of a life? In the case of John Hendrickson, the answer is in the affirmative. Hendrickson, a writer for The Atlantic, wrote about then-candidate Joe Biden’s stutter in early 2020. The article, “What Joe Biden Can’t Bring Himself To Say,” also found Hendrickson recounting his own experience living with a stutter — and resulted in him receiving an outpouring of correspondence from people who directly related to Hendrickson’s memories.

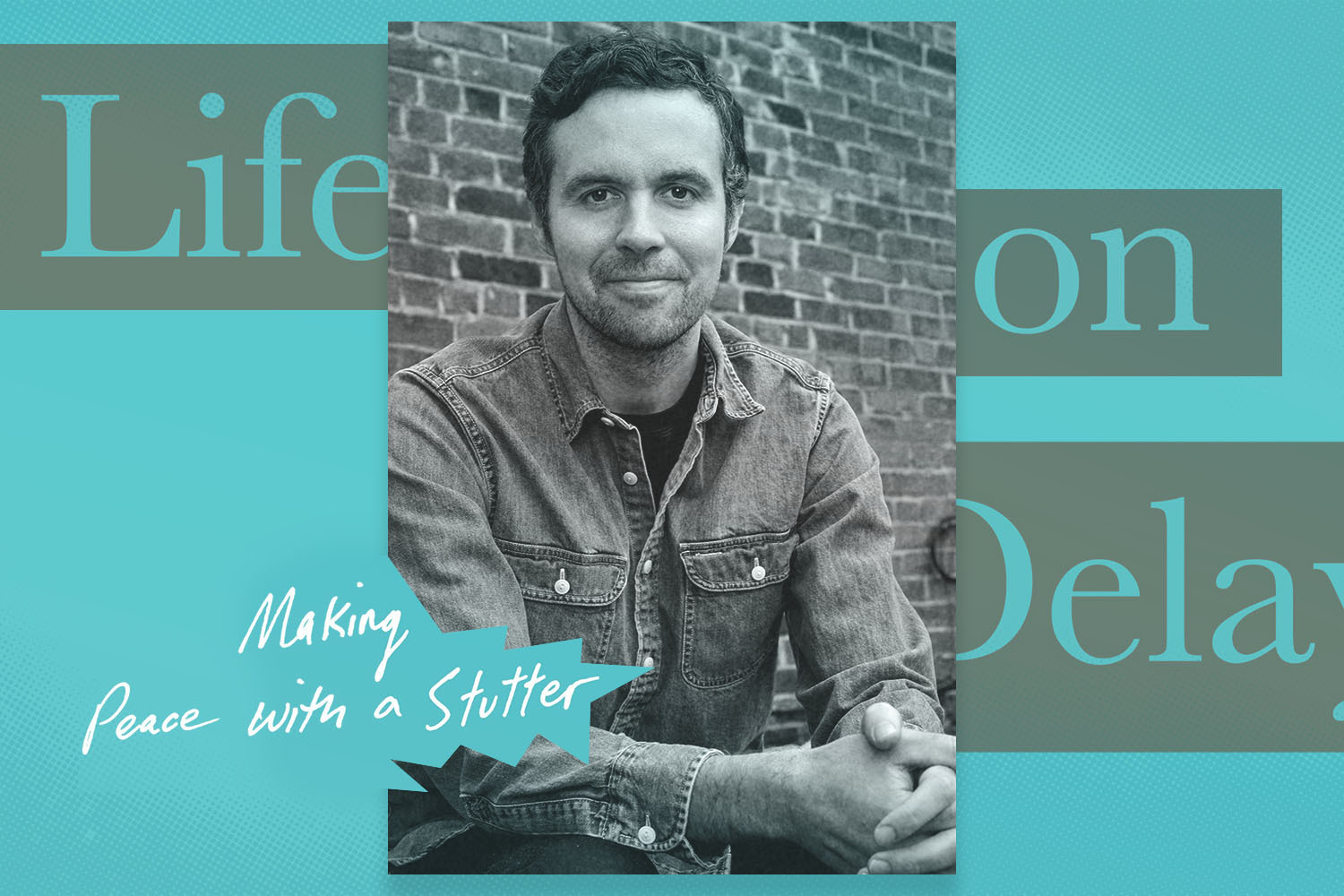

Those encounters provide some of the most emotional moments in Life on Delay: Making Peace with a Stutter, Hendrickson’s new memoir. As he pointed out in our conversation, there aren’t a lot of books out there that stake out similar territory. Prior to reading it, the only other literary work I’d encountered that addressed stuttering was David Mitchell’s novel Black Swan Green, which drew on Mitchell’s own childhood experiences of stuttering.

It’s not hard to see why Hendrickson feels so strongly about his chosen subject. The book’s nuances are also compelling; Hendrickson’s background in writing about music comes up a few times, including the fact that one of the book’s epigraphs comes from a Songs:Ohia song. (Good luck reading the memoir without getting Built to Spill’s “Goin’ Against Your Mind” stuck in your head at one key moment) That blend of personal candor and scientific pursuit help make Life on Delay such a compelling read.

InsideHook spoke with Hendrickson about the memoir, the inspirations for it and one piece of history that didn’t make it into the final book.

InsideHook: Your memoir discusses your own experiences as a writer, but it also talks about the people who you’ve met over the years, and reached out to you in the wake of your article about Joe Biden. From a structural perspective, how did you find the right balance of talking about yourself and talking about how other people have experienced living with a stutter?

John Hendrickson: Finding that balance was certainly at the top of my mind. I knew I wanted to write a memoir, but I wanted it to be a reported memoir — and I was keenly aware that my experience is just one person’s experience and there are plenty of different ways of people who deal with this disorder.

What motivated me to interview people was receiving all these emails I got about Joe Biden from tons of total strangers from all over the world, all walks of life, all different ages, all from different backgrounds who were sending me, in some cases, their life stories. And it just made me feel like I had to look into something, that there was potential for a book there. I knew at the outset that I wanted to include as many different perspectives as I could.

One of the interesting things, for me, in your book was one of your correspondents revealing that their stutter was more pronounced when they spoke Spanish as opposed to when they spoke English. Is that something that happens frequently? Can the language being spoken have an effect on someone’s stutter?

Yes, this is found in every language and every culture. Roughly, 70 million people around the world stutter. I think about three million of them live in America. There’s a very large and robust Indian association focused on stuttering. People I interviewed who are bilingual or trilingual told me that one language is easier than others. I don’t know why, other than this is a neurological disorder with a complex genetic component, and it’s all about the neural pathway and the neurotransmitters. The brain is a crazy beast.

I’m a big fan of the writer. David Mitchell, who I know, has written about living with a stammer. I’m not entirely sure where the line is between one and the other, but having read his work, it felt like it helped prepare me to read your memoir. Is there just not a lot that’s been written about the subject overall, as far as a body of work on stuttering is concerned?

David Mitchell is British, and they refer to it as stammering. That’s just the cultural difference in our language, but it’s referring to the same issues. It’s just two different words for it.

And — no, there hasn’t been a ton of research or writing on this, it’s just not as explored as other disorders and disabilities — partly because it’s only one percent of the population. But also, I think it’s because it carries a stigma. There’s an ongoing movement within the community of people who stutter to de-stigmatize the disorder, the fact remains that many, if not most, people who stutter feel ashamed of it. It can take a lifetime of work to combat these feelings and that’s one of the main things I’m exploring in this book.

One of the things you write about in the book is your work as a journalist and being on the side of asking questions. What’s it like to be on the other side of that following the release of this memoir?

It’s wild, you know, compared to writing an article about Joe Biden in The Atlantic. Prior to writing this book, I had never really done any interviews. I had certainly never done anything like going on TV or radio or podcasts, but I just hadn’t done any interviews, really, at all.

It’s very interesting being on the other side of it and having to talk about your work, but I’m just completely overwhelmed and grateful to anybody who might be remotely interested in this topic or this book at all because it is relatively obscure. So as much as I may hate phone calls, I’m so grateful to be talking to you about this, and showing people about this book.

You mentioned in your memoir that Zoom is something that causes particular issues for you. Does that mean that the pandemic was an especially difficult time for you?

Yes — but it’s also, in a way, like avoidance reduction therapy. The more that I had to keep logging on to Zoom meetings, the more phone calls I had to make, it did get a little easier each time. I’m certainly not at a place where I’m 100% comfortable with either, but I at least at this point I’ve done a thousand of these over the last few years, and it gets a little easier every time.

Part of what makes it so hard is that sort of natural jerkiness is that exists on Zoom. It’s more pronounced when you’re a person used to stuttering trying to chime in to a group conversation and constantly battling that voice in your head, saying that you’ve been talking too long, that people are bored. It can be hard to silence those voices. That’s another thing I’m trying to explore in this book.

What were some of the touchstones you were drawing from as far as nonfiction? You wrote about David Carr’s memoir, and in your acknowledgments, you mentioned Patrick Raddan Keefe’s advice on writing. Were there any books that you could kind of look to for a template for where you wanted to go with this memoir?

David Carr’s The Night of the Gun, absolutely. The concept of interviewing people from your own path, that was something I immediately knew I wanted to do. So I reached out to my kindergarten teacher, my second grade teacher and my sixth grade girlfriend. I had no idea if they would remember me, I had no idea if they had any recollection of the way I talked or anything, or if they would let me interview them at all, but they all said, Yes, absolutely.

And what they told me — that vividness of their anecdotes crystallized these memories, it blew me away and it really filled in the whole picture of this book, because we only have our own memories. To get another person’s perspective on the same moment is such a rare opportunity, and I’m so grateful for it.

Is there anything that you had learned while researching the book that you had wanted to put into the memoir, but decided that didn’t quite fit with the rest of the narrative?

There was a potential chapter that I ended up not including, which was about the Iowa “Monster Study,” which not many people know about. At the University of Iowa, which is the birthplace of a lot of research into stuttering, the researchers went to an orphanage. I believe they got about a dozen kids who were not kids who stuttered. They tried to turn them into kids who stuttered, and it was later alleged to be the It’s kind of the equivalent of psychological abuse.

None of the kids ended up being people who stuttered, but many of them were traumatized for the rest of their lives. About a decade ago, there was a settlement for it. My goal was to interview one or more of the orphans, who — at the time — would have all been in the 80s or 90s. I kept trying to track them down, but none were alive. Then I got a lead on one of them who seemed to be alive, but then they appeared to die in their early part of the pandemic.

I had thought about writing the whole chapter based on talking to their offspring or grandchildren. But I knew I wanted this book to be based around firsthand experience. So just given that it was impossible to interview any living plaintiffs in that case, I decided to not proceed with the chapter. There is a great New York Times Magazine article from 2003 and that has a lot of background, a lot of the nuts and bolts, in that, but that article was written both before the plaintiffs’ settlement.

Do you have a sense of what the next book might be for you? Would you like to keep focusing on stuttering and people who stutter? Or do you see yourself focusing on something else?

I promised my wife that I wouldn’t think about the next book for a long time because I basically hunkered down during the entire pandemic and I was kind of doing two full-time jobs. I just got married last year and I promised her I wasn’t going to think about that for a while. I’m really trying to enjoy this one as much as I can, and I’ve been so heartened to meet so many people who stutter, just in the past couple weeks on my travels to bookstores around the country.

Every night that I do an in-person event at a bookstore, when it comes time for the audience Q&A, I always invite a person who stutters to get up and ask the first question. So far, that’s happened every night — someone will take me up on it, and what’s happened after that is other people who stutter have gotten up and asked questions. It’s been so beautiful and so profound every night. It’s truly been one of the highlights of my life experiencing those moments.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.