The story of Doug Melville’s family is one that’s uniquely interwoven with that of the United States. His great-grandfather, Benjamin Oliver Davis Sr., was the first Black general in the nation’s history. Melville’s grandfather, Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr., was the second Black general in the history of the U.S. — and was one of the Tuskegee Airmen who made a mark on World War II history. (A barracks at West Point is now named in his honor.)

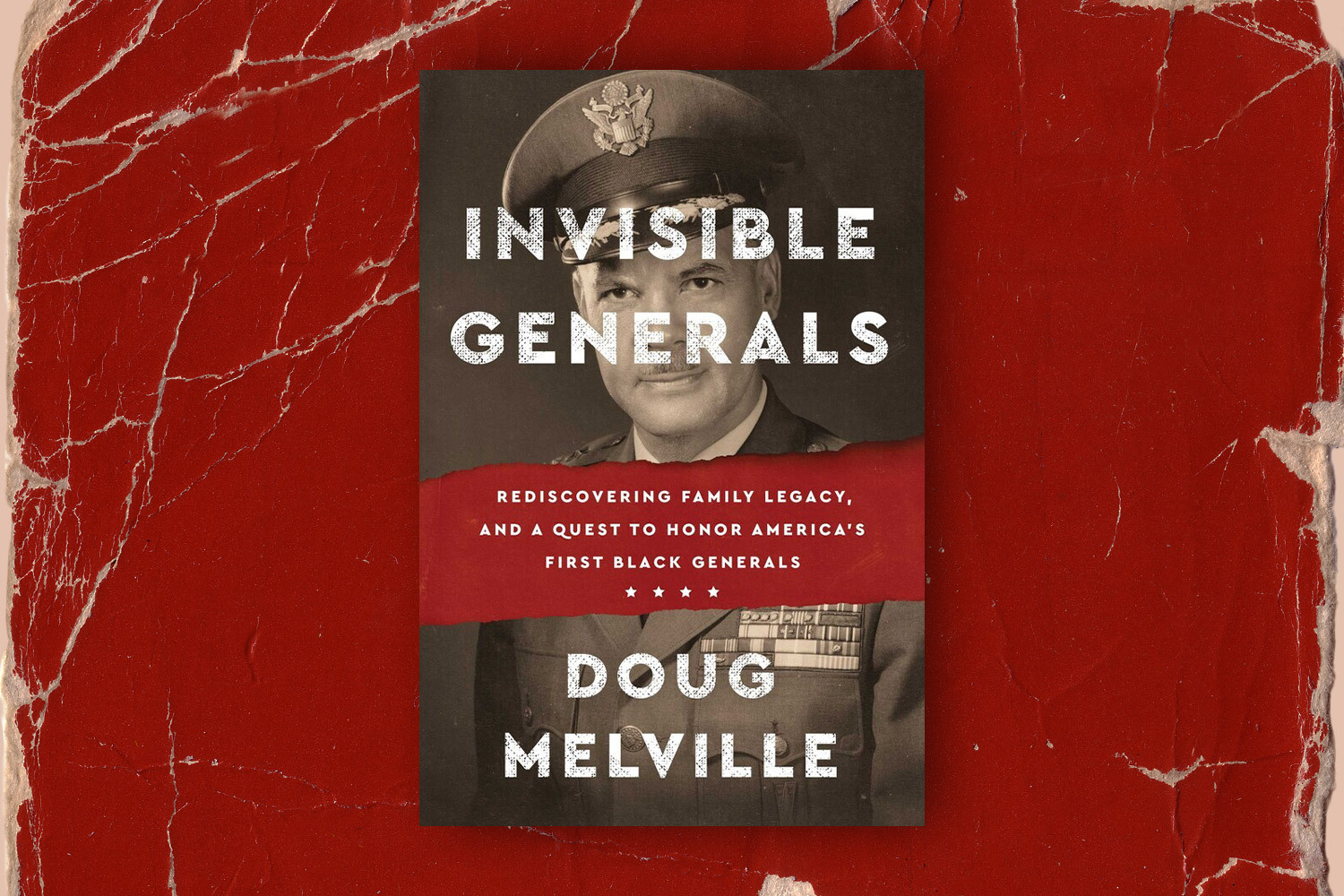

It’s this riveting, extraordinary family history that Melville tells in his new book Invisible Generals: Rediscovering Family Legacy, and a Quest to Honor America’s First Black Generals. The history of Melville’s family is a story that encompasses several presidents (Grant, Nixon, Carter and Clinton all make memorable appearances) and a host of military conflicts. And in discussing what Melville’s family did and did not speak about within that history, the book also offers a powerful look at familial secrets at a turbulent point in history.

Melville spoke with InsideHook about the process of writing this book and the unlikely places that revisiting his family history took him.

InsideHook: How much of your family’s history were you aware of and how much of that was spoken about before you began the process of researching Invisible Generals and after you first saw the film Red Tails and became more concerned about your family’s legacy?

Doug Melville: I didn’t really know too much about it. When we grew up, we just didn’t talk about yesterday. We always talked about tomorrow. “What are you gonna do tomorrow? What’s next up? What do you wanna be?”

When I used to go over to Ben’s apartment — he lived in Arlington, Virginia, [at] 1001 Wilson Boulevard overlooking an airport, so he could see the planes going in and out. When I would go over there, there was no military insignia hanging up in the house. There was feng shui, because he spent many years living in Asia. So they had lightly playing music and statues and artwork — very feng shui.

They would talk politics with my parents, but they never really talked about the military. I wasn’t really putting two and two together, but we would always go to Andrews Air Force Base for Thanksgiving dinner or for different events. And he would always golf at different golf clubs that were military. So I knew he was in the military, of course. And I knew that he was someone of note just by how we would talk, but we never talked about it. I didn’t even know he was a pilot until probably high school.

So what was the research process like? You mentioned in your book that Ben had written an autobiography, but besides that, how much of this information was readily available and how much of this involved going into different archives, whether it be the Army or the Smithsonian or other places?

Well, after I talked to my dad about it, he had a lot of stories. My dad had so many stories because it’s a firsthand account. So really what he was telling me wasn’t available, but he was able to give real context about, “This is what it was like going to Tuskegee. And when I went on the train, this is how we were treated.” He would go and say, “These are my pictures of segregation that I took.” I really was able to get the human side of it.

I think the challenge when you read someone’s older military biographies, it’s all military. It’s just stats and facts, which are important, but it doesn’t really help with the story so much. You get lost if you’re not too familiar with it, but my dad was able to really tell me the human side of how it was growing up or how the car rides were — little small things where you just needed to have someone who was there firsthand.

Once the movie Red Tails happened, that’s when my dad really sat me down and told me a large part of the story of Ben and his dad. So he would call him Ben; my dad is his nephew by blood, but my dad was raised by him from the time he was seven years old. We kept our last name Melville. My dad called him Ben; Ben called him Larry or Scott. That was just how the relationship went because there was just always a fear. And then Ben was in charge at that time, commanding what would become the Tuskegee Airmen, so there were just a lot of eyes on him. Everything was very invisible: stay silent, don’t raise your hand, don’t speak loudly. Everything was exactly to the books, so there was no confusion, they lived exactly like living in a Microsoft Excel file. There was no going outside the box.

My dad was raised like that, as a judge, his paperwork, breakfast at the same time, set up the plates the night before, toast. They grew up in a way that is not how I was naturally. So the storytelling part never was part of it. They never talked about it. They always asked me, “What do you want to do? It doesn’t matter how we lived. We want you to be successful. You’re the future.”

I don’t know if it was a mental health remedy or if it was a way to move past it. You know, you don’t really know that part of it. But when my dad told me the story after I watched Red Tails, that’s when I started researching it. Because for me personally, it was hard for me to understand how I’d never heard this story, and how other people had never heard this story. It wasn’t really calculating with me how this could be.

That’s what started me going to the museums. I started simply just going to eBay, Google — really late nights in Google — going to museum archives. It was just the beginning of that part. When Ben got his fourth star in 1998, that was really when I knew that he was amazing. Before that he paid for my college.

He paid for my first car, a Honda Accord. He gave me my first set of golf clubs. Woods made from real wood. He got me my first computer, my Apple IIe. He did many things for me, so I knew he was comfortable, but until he got that fourth star — that was when we were at the White House — I was going, okay, this is on another level.

That was really what spurred my curiosity. But I was just graduating college, trying to get my first job. So, you don’t really look at the family like that sometimes.

In Invisible Generals, you write about finding Ben’s archives at the Smithsonian and the detail that emerges from there that you described as shocking — and felt very shocking when I encountered it as a reader. Was there one particular place that you did research that stood out to you as being key to the overall story that you were telling?

There were a couple of photos, like Ben walking through the first airport metal detector. That was very interesting, because you read that he led the creation of the airport security, but that’s just me saying it to you. But when you see that photo in 1971 of him walking through it, testing it at a conference right outside the Pentagon, then you think, “Okay, this is really real.” Or the picture of him with Jimmy Carter unveiling the 55-mile-an-hour speed limit. That was crazy to me.

Maybe it’s just from coming of age in a more partisan time, but it seems telling that he was also someone who both the Nixon and Carter administrations put a lot of trust in.

I did write in the book too that he never voted. He never wanted someone to find out and then they use it against them. So even though it’s supposed to be a private matter, he just felt that it could only be used against him. I mean, he’s so ingrained in a political system, but for many high level officials in the military, their boss is their boss and that’s how they look at it. It’s the chain of command. I’m assuming many vote. So that was shocking.

The Army War College in Pennsylvania — they were really nice people that worked there. I had no idea where Ben Davis Senior’s archives were — because no one really talks about Ben Davis Senior as the first Black general, but if there’s no him, there is no Ben Davis Junior. That’s the whole story. If there’s no him and Ben, there is no Tuskegee Airmen.

He’s critical to the story. So when I found out his archives were located in the U.S. Army War College in Pennsylvania, all I had known about the U.S. Army War College in Pennsylvania for during my years of research was the 1925 U.S. Army War Report that they wrote stating that the Negro was inferior. So the big learning experience for me was that the same institution that wrote that letter owns and controls nearly 100% of Ben Davis Senior’s archives. The family doesn’t have them, they have them.

Now they were donated by Ben’s sister and they showed me the paperwork and they were gracious and nice people. I’m just saying — to me, there should be a level of a morality clause with these museums, with the government. Elevating someone to a fourth star and telling them they can’t get compensated; taking materials from the museum, never letting the family either monetize them or even see them. You have to write all these letters.

At some point in this conversation, there has to be a level of a morality clause. Everything can’t be capital, capital, capital when you’re dealing with families and grandkids and legacies that are still alive and breathing today.

When you brought up the issue of making Ben a four-star general but not giving him the sort of increase in pension or salary that that would normally come with — something similar to what another Tuskegee Airman also went through — that was unnerving to read. You’d think that whatever dollar amount that was would be miniscule in the military’s overall budget for a given year.

I think that, to me, the biggest shame is acknowledgement without the compensation — but also go where you’re compensated. That is so important. And to be honest with you, the moral high ground is the most expensive real estate in the world. I write about it in the book. To me, that is what all this is about. I’m not saying it’s easy, and it’s not going to happen overnight and it’s subjective and the line is gray, but at a certain point, we should have some level of, whatever we want to call it, a compassion clause.

To acknowledge that people were overlooked through their entire life’s work and do it at the White House of the United States. There is no other place. The president is doing it. And then to sign a piece of paper that says you will not get compensated in the past or the future. It was 40 years.

It’s absurd in the worst possible way.

Yeah, it was. And that was the whole thing about him and his wife at the house, how much tension it caused. She just wanted to be compensated if we were going to be celebrated. And then he said, “What difference does it make?” Because if you’re a general and you want to get that fourth star that you worked for and dreamed about and knew you earned it and you didn’t get it, this is your holy grail. So you’re not going to say no. So it’s a difference of opinion.

You Can’t Tell the History of Menswear Without the History of Pockets

Hannah Carlson on getting to the bottom — literally and figuratively — of “Pockets”The book begins with you seeing the movie Red Tails and being frustrated that some of the names of the real-life Tuskegee Airmen were not included. Now that you’re telling the story, do you foresee a place and time where some of those names could become better-known?

Yeah, I would love them to be. I think the challenge now is you’re dealing with World War II veterans that are heroes, but are aging. World War II was quite some time ago. There’s not that many of these men or women alive. I think everyone from Lucasfilm is amazing and no one did anything wrong. They were so gracious there. They helped bring the story to the world.

All of that is true, but two things can be right at the same time. I would like to start with people knowing Ben as the commander of the Tuskegee Airmen and his dad who worked with the president to get it approved. Then we can look at how we can get other names of other men more in the narrative, in the conversation, so we could start building more heroes who did unbelievable accomplishments.

The challenge is that we’re far from World War II. And as the generations go on, you know, for some people, they don’t even know how far back it is. And even I forget too — I’m in my 40s, but even when you say 9/11, grown people are alive that weren’t even alive then.

It boggles my mind every time I think about it.

Yeah, your 22-year-old intern doesn’t even know what you’re talking about.

It’s hard to translate the feelings of history sometimes unless you do it through big stories. And I think when you look at big stories that we tell in the American narrative, I feel like this story should be just as big. But you don’t know it until someone goes in and really presents it in a way where you realize it’s part of the American tapestry that we should know.

Was there anything in particular that stood out as you did the research — whether it was about your family’s history or American history in general — that really just surprised you and that you had had no idea about beforehand?

One of the most surprising things was that Ben’s grandfather was in the presidential carriage with Ulysses S. Grant with his son on his lap during the presidential inauguration.

With your own family story, it takes you from Ulysses S. Grant on up to Bill Clinton and John McCain over a century later.

Yeah, and the modern day people shaped it, McCain getting [Ben’s fourth star] passed and Clinton putting it on.

One of the other things — maybe “surprising” isn’t the right word — was how amazing West Point Military Academy has been with everything. That was very unexpected from day one, because this started in 2015 when I emailed them and they didn’t know us. Our family never spoke about West Point because that was just a place Ben had to go. And when I emailed them, it was unexpected.

Also, the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum showing me the actual letters that were written. Even the Army War College, they brought me to the office with the pink and yellow papers in a box and said, “Here is every single transaction with your family.”

The overall thing would be how interested others are and warm they are, because they are working at these places and they are engaged in the story to the point where they said, “We want to show you the information.” I thought they were going to say, “Oh, we don’t wanna show you.” And this was my bias. I thought this was going to be very hard to see, or contentious, but they were very, very, very open.

The Smithsonian Air and Space Museum bakes the cookies and other things that were Ben’s favorite because they donated a cookbook. They have bake sales with the items made by the staff of the bake sale items from this cookbook from 1940. And so that was very shocking.

The curator at the Air and Space Museum was very helpful. She showed me all the letters. She told me stories. She was working there when the items were brought in. So that, to me, was very surprising, but in a great way that made me feel really good that I was there and could humanize these boxes and these statues and pieces of metal and paper that are just sitting in crates and say, “This is a real family.”

I found pictures of my dad in there, tons of pictures of my dad that he had never seen. He just turned 90 this week. He was there for, you know, so much of it firsthand, but also just to give him joy in this stage of life where you have more days behind you than you do ahead. So it’s good that small things matter.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.