You can’t escape William Shakespeare. You read his plays and poems in school and have seen his works adapted into everything from Disney films (The Lion King) to ’90s teen comedies (10 Things I Hate About You). You probably also regularly quote him without realizing it: phrases like “wild-goose chase,” “green-eyed monster” and “wear your heart on your sleeve” all owe their etymology to the playwright. For over four centuries, our comedies, tragedies and everything in between has in some way been influenced by The Bard of Avon. His work is so fixed into our shared cultural brain that it’s probably second only to the Bible in terms of how it has shaped our world.

In 2019, when we seem to disagree on every subject, you might think that Shakespeare would be the one piece of common ground. But you’d be wrong.

Last week, the New Yorker published an article about how the late Supreme Court justices John Paul Stevens and Antonin Scalia believed Shakespeare’s works were written by Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. In May, The Atlantic published “Was Shakespeare a Woman?”, an article by Elizabeth Winkler that proposed the aristocratic poet Emilia Bassano — despite admitting Bassno’s “writing style bears no obvious resemblance to Shakespeare’s.”

Shakespare conspiracy theories are hardly new. Although no one is known to have contested Shakespeare’s authorship during his lifetime, controversy has swirled since at least the 19th century, when Henry James said he was “haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practiced on a patient world.” Later, Charlie Chaplin was adamant that the true author “had an aristocratic attitude” and wasn’t a glover’s son. Sigmund Freud, Malcolm X, Helen Keller and even Shakespearean (or “Shakespeareian”?) actors like Derek Jacobi and Mark Rylance have all expressed doubts.

So Long Lives This Conspiracy, and This Gives Life to Other Ones

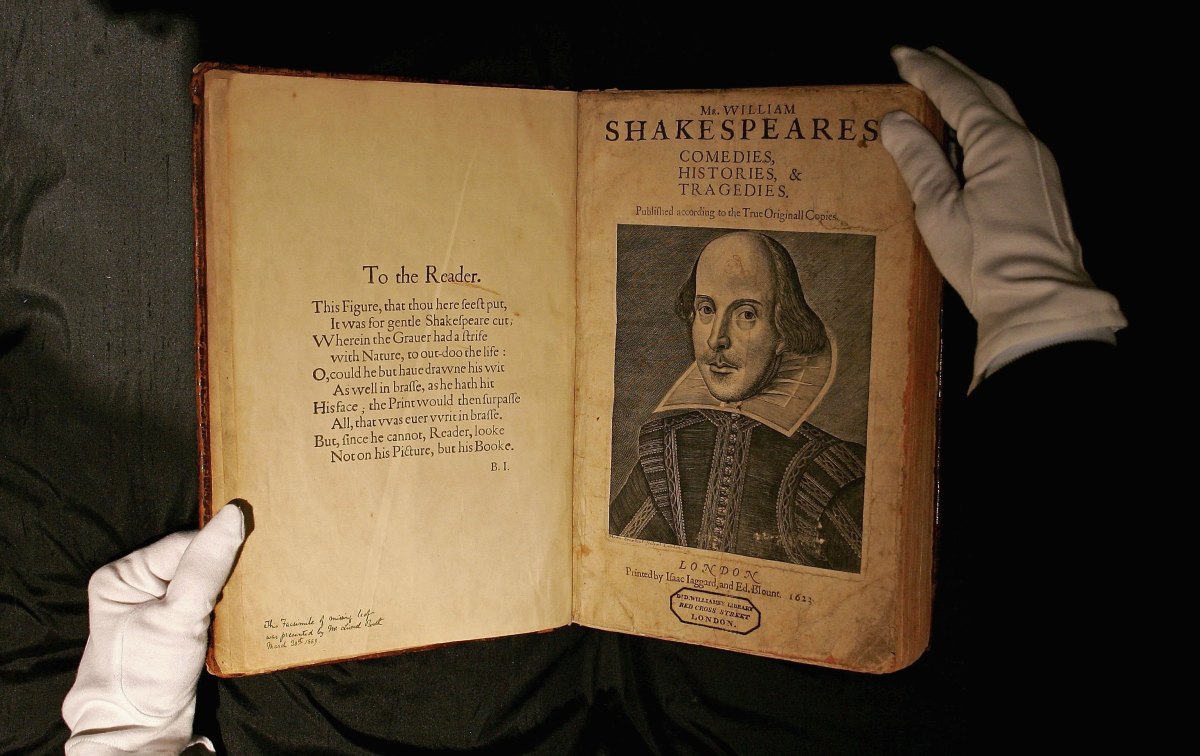

William Shakespeare, according to the actual evidence we have, was born to an illiterate glove-maker in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564. He grew to become a celebrated actor and playwright who performed for royalty and was about as close to a rockstar as Elizabethan playwrights got. After he died, most of his works were collected and preserved in the First Folio. That was that … for a while.

Until the 1800s, the debate was not about whether Shakespeare was a fraud, but rather whether he was really all that great. Ben Jonson and John Fletcher were generally thought to be superior in the centuries after his death. But critical evaluations shifted, as they are wont to do, and by the 19th century Shakespeare was becoming enshrined as the greatest English-language author of all time.

Not long after, the theories began to come out of hiding.

The history of Shakespeare conspiracy theories is almost as wacky as the theories themselves. It involves a host of crackpots and grifters, but also some of the world’s most celebrated minds. Sigmund Freud, for example, used Hamlet as part of his Oedipus Complex on the belief that Shakespeare wrote the play following the death of his father. After Frued learned it was probably written before, he switched to the Earl of Oxford theory of authorship.

Another popular theory is that the better-educated playwright Christopher Marlowe was the true author. One problem? Marlowe died in 1593, long before Shakespeare’s most famous plays — like Hamlet, Macbeth or Romeo and Juliet — were published. The theory goes that Marlowe faked his own death to become “the Elizabethan James Bond” while also finding time to pen the greatest plays of all time. Marlowe, it seems, was really busy.

Marlowe isn’t the only supposed author who wrote plays from beyond the grave. As James Shapiro, author of the excellent book, Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?, noted about the Earl of Oxford theory: “Perhaps the greatest obstacle facing de Vere’s supporters is that he died in 1604, before 10 or so of Shakespeare’s plays were written.” As if covertly authoring the greatest plays of all time wasn’t enough, the Earl of Oxford theory is often spiced up with suggestions that he was also secretly the heir to the throne.

Romantic, bizarre and implausible theories tend to attract people with, well, other strange beliefs. While researching this article, I stumbled across an Oxfordian’s blog in which the comments descended into a debate about whether Shakespeare was “‘inspired’ in some way by discarnate entities” or if he simply “had all the experience he needed from the king’s court and abroad in previous lives.”

But ghosts and secret Tudors are only the beginning. If you don’t like those theories, you can you can take your pick from just about any person who lived at the time. Wikipedia’s “List of Shakespeare authorship candidates” contains 87 names including the entire orders of the Jesuits and the Rosicrucians, the Queen of England and Mary Queen of Scots.

To Believe or Not To Believe?

Throughout the years, backers of the different possible bards have tried everything they could to find some evidence of their preferred person. They’ve built a mechanical “cipher wheel” and searched for hidden codes in secret societies. They’ve held mock trials with Supreme Court members (the court decided for Shakespeare) and run computer analyses of the various claimants (conclusion: “far too many things ‘don’t fit’ for Oxford to be a plausible claimant”). Ultimately, not a single bit of real evidence has been found for any other claimant.

So why are people so willing to believe evidence-free theories involving secret agents, faked deaths and unknown royals over the far simpler theory that the guy whose name is on the plays was the actual author?

One answer is simple snobbery. It is impossible for many people to believe that a (“eww”) commoner with minimal education could have written great plays. Justice Stevens mocked people for thinking “a commoner can be such a brilliant writer. Even though there is no Santa Claus, it’s still a wonderful myth.” As the New Yorker put it, a secret nobleman ghostwriter “explains why the plays are so good.”

The reality is that most of the “evidence” given by anti-Stratfordians is either cherrypicked or incorrect. For example, much is made of the fact that Shakespeare never left England, yet his plays feature the geography of Europe. (Hint: maps existed.) Less mentioned is the fact that Shakespeare made basic geographical errors, such as claiming Bohemia (modern Czech Republic) had a coastline.

When it comes to known facts, the paper trail for Shakespeare is a lot longer than the anti-Stratfordians pretend.

It may be hard to imagine a “commoner” wrote such brilliant plays, but it’s harder to imagine how this conspiracy would have actually worked in practice. The real Shakespeare was undisputedly a famous actor who was involved in the small and gossipy London theater world. He knew and worked with the other famous playwrights and actors. He was involved in the productions. He collaborated with other writers. If he was a fraud, especially an illiterate and uneducated one, wouldn’t everyone have known it?

A Conspiracy By Any Other Name…

From birtherism and Pizzagate to climate change denial to anti-vaxxers, we increasingly live in an age of conspiracies. At some point, the information superhighway took a turn into a garbage fire of nonsense, trolling and lies. This makes it all the more astonishing that leading magazines would uncritically spread Shakespeare theories. As the critic and host of Slate’s Shakespeare podcast Isaac Butler said, “if Justice Stevens was a climate change denier (or super into “race science”) and got an award from the Koch brothers, would you cover that story whimsically and without any serious rebuttal of that POV? No.”

In addition to being a Shakespeare expert, Butler studied conspiracy theories for his own theatrical work, Real Enemies.: “Conspiracy theories in general — and that’s all we’re really talking about here — arise when the very normal narrative-making function we all possess inserts some causality between data points that don’t really go together,” he tells InsideHook. “This is done for all sorts of reasons, but in general it’s done to make sense of the world and, in particular, one’s powerlessness within it. So the effects of climate change (for example) get explained as a government technology program to control the weather called HAARP. The anxiety is causing our brains to make a story, but the story it makes is factually wrong.”

While there’s no evidence that anyone else wrote the plays, as Butler says, “Shakespeare’s biography and the documentary record about it does contain all sorts of gaps.” It contains less gaps than many of his contemporaries, but the 16th and 17th century wasn’t exactly known for expert record keeping. “Additionally,” Butler mentions, “I do think for some people it is anxiety-producing that the son of a glover with an 8th-grade education created the greatest body of work of any writer in human history.”

One thing the Shakespeare conspiracy theories show is how easily it is to distort facts about a subject that one doesn’t truly know much about. If I tell you William Shakespeare only received a “grammar school” education, you might understandably think of your rather lax and recess-filled 20th-century elementary school American education and think, “I could never have written a play back then!” You likely don’t know that in Shakespeare’s time, the literary education was far more rigorous, and even as a plebeian, he would have read Cicero, Virgil, Erasmus and others in Latin.

This is the same way other, more dangerous conspiracy theories work. If you don’t have a background in medicine, it’s easy to be mislead about how vaccines work. If you don’t know how the intricacies of the American electoral system actually works (and few Americans do), it’s easy to believe that “millions” of illegal votes were cast in the 2016 election. Every day, the world gets more complex while most of us don’t grow any more powerful. Conspiracies are one way to grab a bit of control.

As the Shakespeare professor Stephen Marche has said, the idea that Shakespeare didn’t write his plays “has roughly the same currency as the faked moon landing does among astronauts.” But most of us aren’t astronauts. And most of us aren’t scholars of Elizabethan theater. All we do is listen to the people who have actually studied these subjects and hope they agree with Mariana in All’s Well That Ends Well when she remarks that “no legacy is so rich as honesty.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C750)