Generations of moviegoers have geeked out over the onscreen adventures of James Bond. And as with any storied onscreen character, ever so often a little revitalization is needed to keep things fresh. The most high-profile example of this in the Bond films in recent memory remains the casting of Daniel Craig, which coincided with a more psychologically immediate and visceral take on the character — a post-Bourne Bond, as it were.

The latest onscreen adventure for Bond, the forthcoming No Time to Die — which was postponed to a November 20th release date due to coronavirus — is no slouch when it comes to impressive talent behind the camera as well: the presence of director Cary Joji Fukunaga and the involvement of writer Phoebe Waller-Bridge offers plenty of grounds for optimism.

But Casino Royale wasn’t the first time Bond received an onscreen overhaul that went beyond a new actor in the role. In the new book Nobody Does it Better: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of James Bond, Mark A. Altman and Edward Gross offer readers a comprehensive look at the James Bond films to date. It’s a fantastic behind-the-scenes look at one of the most enduring onscreen characters of our time.

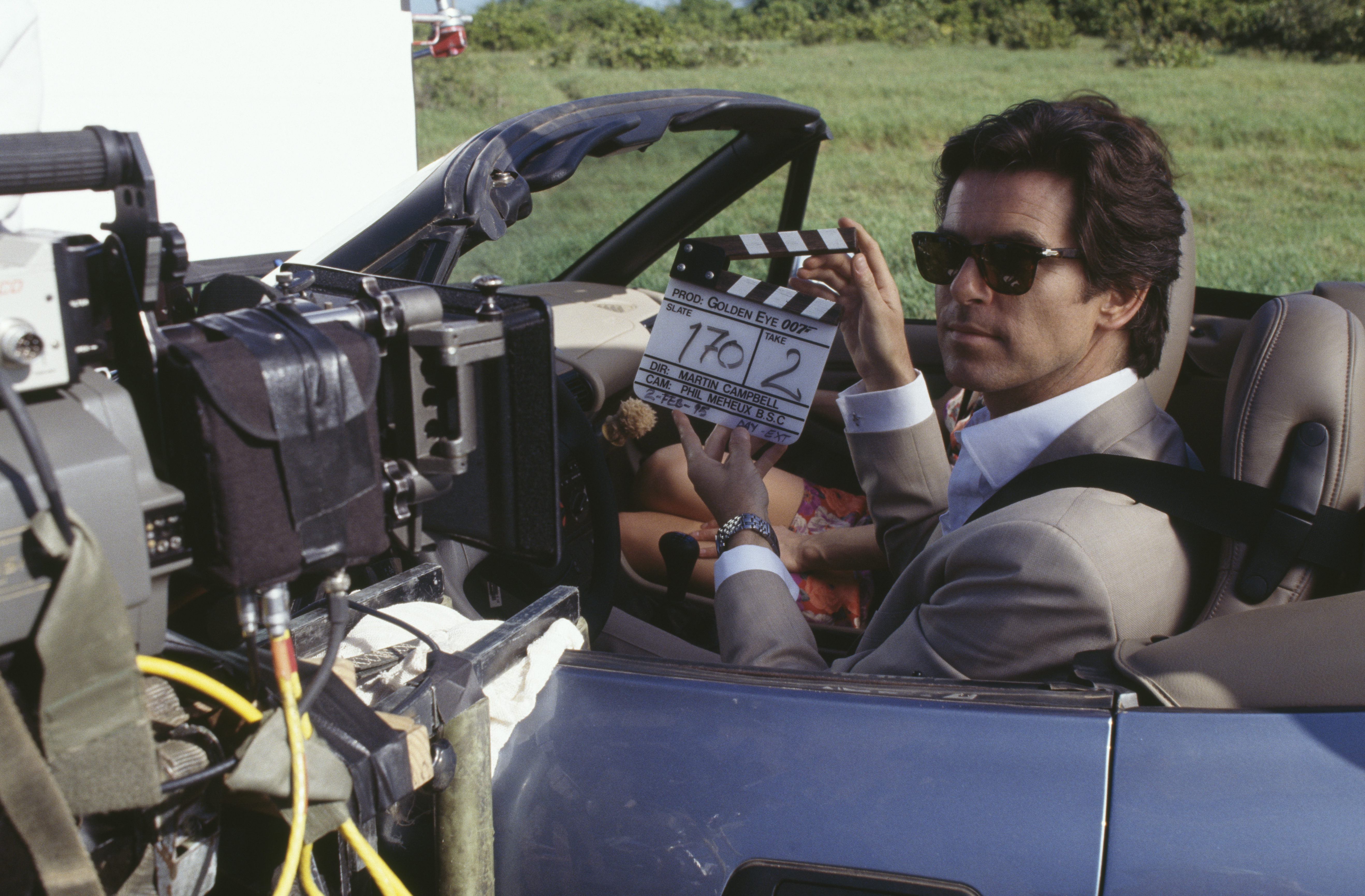

Some of the most fascinating anecdotes to be found in the book come from the history of 1995’s GoldenEye, the first film to feature Pierce Brosnan as Bond. He replaced Timothy Dalton in the role; perhaps coincidentally, both actors have gone on to play gloriously sinister roles in the Edgar Wright-directed Cornetto Trilogy.

Altman and Gross reveal that there were a few other options under consideration before Brosnan came on board. There’s a reference to an earlier concept for the 17th Bond film which, had it been made, would have “feature[d] animatronic creations from Walt Disney Imagineering.” The mind boggles at what this might have involved.

Among the key things that can be gleaned from the interviews in Altman and Gross’s book is the way that the aging of James Bond as a concept contributed to the development of GoldenEye. “When Dr. No was made in 1962, people didn’t go to the Caribbean, so for all of us in those days it was very exotic,” said GoldenEye director of photography Phil Méheux. “Now everyone has traveled all over the world, and that, to them, was no longer an excitement. That’s what made us change the way the films are made.”

Screenwriter Bruce Feirstein offered a similar commentary on the film’s story and point of view. In a conversation between Feirstein and director Martin Campbell, the two “realized that the world had changed, but Bond hadn’t.” For Feirstein, that gave the film a distinctive point of view. “Every scene in that movie is filled with that conflict,” he recalled.

Reading Feirstein’s recollections, there’s a strange parallel with Robert Altman’s concept of “Rip Van Marlowe” from his Raymond Chandler adaptation The Long Goodbye. And while comparing the two films beyond that might be something of a stretch, that added dimension does offer one reason why GoldenEye resonated in a way that many of its predecessors had not.

Reading through these accounts of the film’s development and production, one can also find a few potentially clashing approaches. Ray Morton of Script magazine observed that “[screenwriter] Michael France’s major contribution to the series was to reinvent the James Bond films as a mid-nineties action movie.”

But another one of the film’s writers, Jeffrey Caine, spoke in his interview about how “[t]he whole idea of doing this film was to get something back of the flavor of the early Bond films.” As the franchise gets older, that push and pull between nostalgia for the earlier installments and the need to make a movie that fits in with contemporary action filmmaking can sometimes be detected on screen (case in point: 2015’s Spectre).

As action fans await James Bond’s next onscreen adventure, this expansive oral history offers plenty of inside information on where the character has been and why he’s so appealing. As the title suggests, nobody does it better indeed — but this new book goes a long way towards casting a light on the effort that it takes to do it at all.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.