Released in 1997 the year after he was part of a disastrous Mount Everest expedition that resulted in eight climbers being killed when a blizzard struck near the summit, Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster was a national bestseller and helped earn him the Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1999.

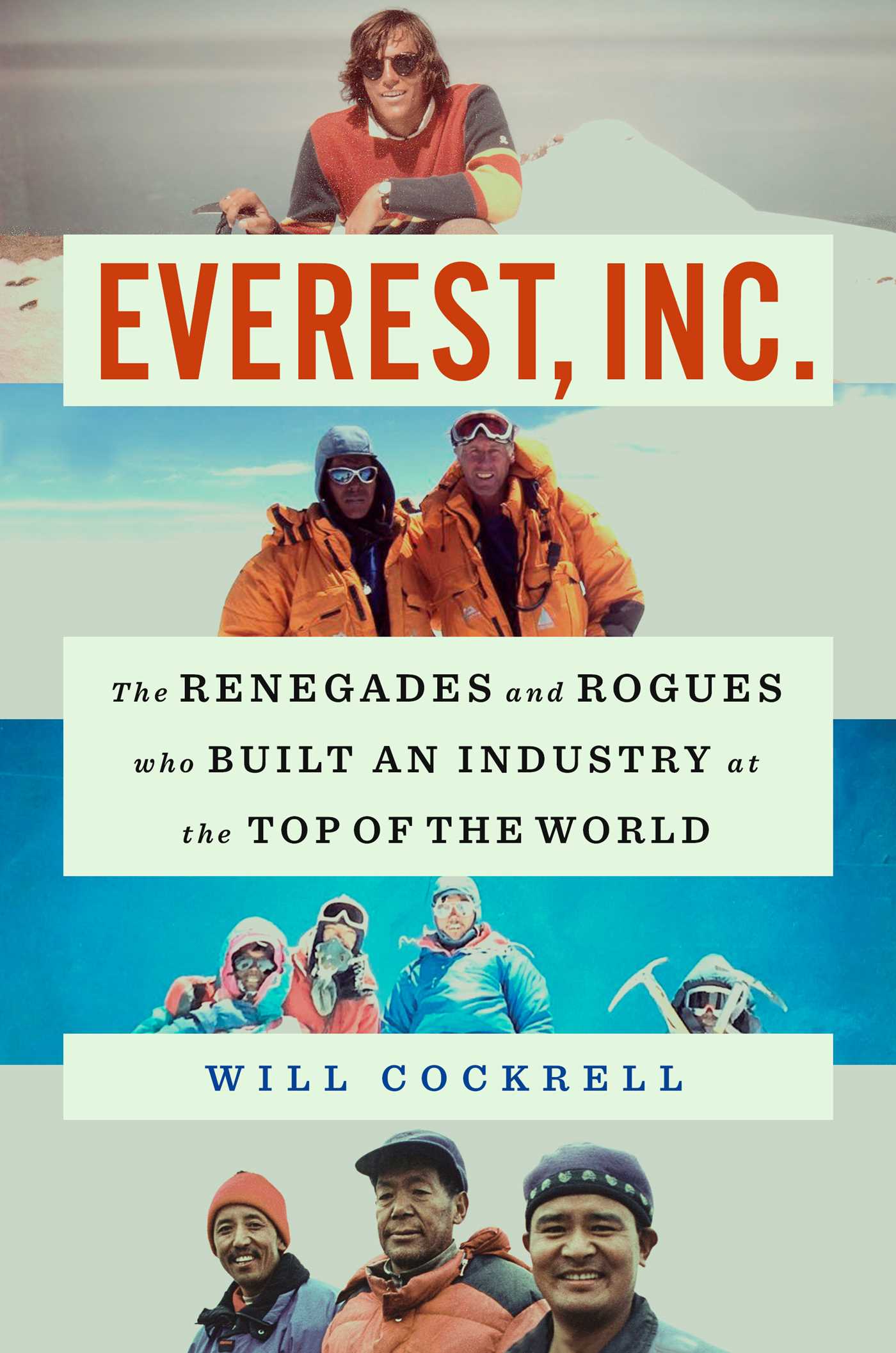

In his new book, Everest, Inc.: The Renegades and Rogues Who Built an Industry at the Top of the World, award-winning adventure journalist Will Cockrell re-contextualizes Krakauer’s work from nearly three decades ago by interviewing key Everest guiding industry players to see what Into Thin Air got right — and wrong.

As this excerpt from Everest, Inc. points out, Krakauer’s attempt to take take down the then-fledgling guiding industry may have had the opposite effect and instead attracted an entirely new group of climbers to Everest.

Given Krakauer’s own horrific experience in 1996 and subsequent grieving process for the friends he’d lost, it’s understandable that he would lash out at those he felt played a part in the degradation of climbing. Yet the fact is, you’d be hard-pressed to find an Everest guide who is a fan of Into Thin Air, and it has little to do with self-preservation. To them, his view of climbing is far too narrow, and he doesn’t get what guiding is about. He caricatured Everest clients too simplistically, and encouraged people to judge their motives and actions from afar.

Dave Hahn has known Krakauer for more than thirty years and counts him as a friend, but says they bicker. After getting his start at RMI, Hahn began working for IMG and soon became one of the best mountain guides not only on Everest, but throughout the world. Hahn’s grace on steep snow and ice and distinct physical features — tall, with a pronounced nose and chin, and huge hands — make him seem larger than life. He likes to tell stories and is known for his subtle one-liners and self-deprecating sense of humor.

The Nova documentary Mountain of Ice is a fascinating window into Hahn’s dynamic with Krakauer. The film is about a team of climbers on Mount Vinson in Antarctica in 2001, of which Krakauer, Hahn and Conrad Anker were members. On camera, Krakauer becomes frustrated with Hahn for suggesting a safer route that will allow the less experienced documentary crew to continue ascending with them. Krakauer says that it may be time to just leave the crew behind. “I’ve been on one guided expedition in my life and it was the biggest mistake I ever made,” he says, referring to 1996. “I’ve seen what happens when very good guides make one bad decision with clients who don’t have the skill or experience to look after themselves. I swore I would never be in this position again.”

Alex Honnold’s Biggest Worry While Free Soloing Isn’t Falling. It’s Climate Change.

The world-renowned rock climber talks about sustainability and climate activismBut Anker is in charge, and defers to Hahn, who held the record for most summits of Vinson at that point as well as of Everest, among Western climbers. They all end up summiting together as a group.

“Dave was right, it worked,” Krakauer later says to camera. “It was a remarkable bit of guiding. I came away with a great deal more respect for him after seeing what he did.”

He might have respected Hahn, but he hadn’t changed his mind about guided clients. Those who hired Hahn because they didn’t have the experience to ascend and descend a slope safely on their own were still a problem, in his eyes.

“I just never thought that Jon understood guiding at all — despite the fact that he’d written the best-selling book about guiding,” says Hahn today. “He didn’t view it as legitimate, he didn’t view guided clients as climbers, didn’t even view guides as climbers. I do go into less dangerous settings than Jon, or, say, Conrad, but I’m happy to do it regularly, with novices, and depend on their abilities and my abilities. I was once a client.”

Something else that Krakauer didn’t — and perhaps couldn’t have — understood was the effect that Into Thin Air would have on the Everest guiding industry. He assumed his story would serve as the ultimate cautionary tale about the mountain. So did David Hamilton, a Jagged Globe guide who had not been to Everest yet but was guiding often on 7,000- and 8,000-meter mountains in Pakistan when Into Thin Air came out. “I remember thinking nobody was going to want to go to Everest now — and that I’ll probably never get to guide Everest. In fact, I remember Steve Bell saying, ‘Welp, I guess we’ll just have to focus on the six other Seven Summits.’”

But Eric Simonson — who was not on Everest but with clients on Cho Oyu in the spring of 1996 — immediately recognized what was coming next. It was Bass’s Seven Summits book, times ten. “I knew our Everest business was about to go through the roof,” he says.

Simonson understood a crucial, uncomfortable fact: the specter of death is not a deterrent — it’s what makes many people want to climb Everest in the first place.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C750)