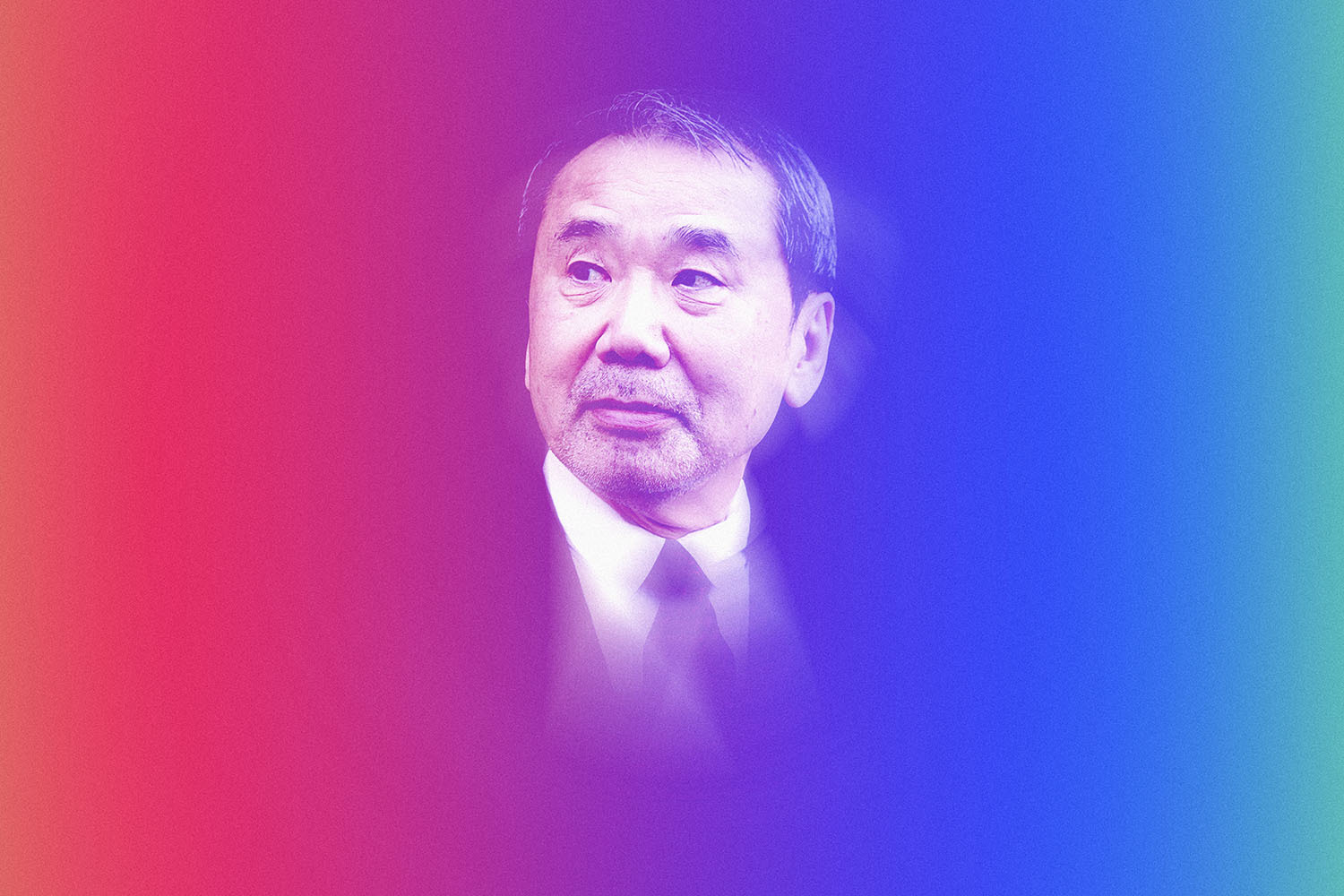

When I saw Nobel-winner Kazuo Ishiguro’s new novel was out earlier this year, I was obviously intrigued, but I decided to sit out picking up Klara and the Sun, at least immediately. Ishiguro is one of the rare “must read” writers, the type for whom I’d usually drop everything I was doing, but this time around was a little different. Even though I loved his last few books that were in similar fantasy/sci-fi territory as his latest, in 2021, I’d rather save anything that includes “dystopian” in the jacket copy for a time that feels, well, less dystopian. Once we don’t have to worry about being in the middle of a pandemic and we’re all (hopefully) vaccinated and just worrying about whatever it is we worried about before COVID, I’ll return to it.

But that doesn’t mean I didn’t pick up a novel by Ishiguro this year. No, instead, I actually reread my favorite of his books, 1989’s The Remains of the Day. I didn’t do it because I felt bad about not reading his latest. Instead, I picked up the book because over the last year I’ve found a lot of comfort in reading or watching anything that involved an English butler, and The Remains of the Day might be the greatest work about an English butler there is.

Butler fiction isn’t really a thing. Instead, the butler always plays a part in another person’s story. Mr. Stevens, the narrator in Ishiguro’s 1989 novel, is one of the few exceptions to this rule. Stevens is a butler, and his is the point of view the book is told from. The point of view, however, is shaped in a very specific way, an older way from an older England, one that is passing by Stevens and the great house he keeps, Darlington Hall. Starting and ending in the middle of the 20th century, the idea of the British butler was already becoming an outdated one. The British aristocracy they worked for had seen their powers limited by the Parliament Act 1911, and the way of life they had known for centuries slipped away.

The Remains of the Day is, in my opinion, a perfect novel, but it was also a little bit heavier than the other butler fiction I spent my time with throughout the pandemic. I finally finished off the final three seasons of Downton Abbey (I had initially abandoned it after the third season went off the rails one too many times), and decided that the best part of the show wasn’t the Crawley family, but the people who made the house run. The maids and cooks and footmen and butlers were the best part of the show, and I tried to focus my attention on them as I finished up the series. After that, I decided to work my way through as many of the P.G. Wodehouse books that feature Bertie Wooster’s faithful valet, Jeeves, as possible. I would have also watched all of the early-1990s Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry take on Wodehouse’s most famous characters, Jeeves and Wooster, but for some reason it’s not streaming in the States.

The English butler in fiction sometimes feels like a trope that isn’t long for this world, at least not the type done with the sort of nuance of an Ishiguro or Wodehouse. Maybe some smart young novelist will look to the rise in demand for English butlers among the new-money billionaires from Russia or China as a source of inspiration for their books, but I’m not holding my breath.

Maybe the butler’s disappearance also owes to the fact that the very traits that define him are no longer in high demand. He is almost always supposed to be the most trustworthy person in the household. A rich person can hire a butler and believe that they can say or act however they like, and the butler won’t tell. The butler also tends to be wiser than he lets on. In the case of Jeeves, his smarts help get Bertie Wooster out of a number of predicaments. Wooster, meanwhile, is a spoiled schmuck who is oblivious to just about everything. Fiction won’t be running out of rich schmucks any time soon, but writers are becoming less forgiving of them, and perhaps removing the safety net of a dutiful butler is one way to achieve this.

Another reason the butler might be disappearing from stories is because he’s almost always the straight man. On American television, from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air to The Nanny to Mr. Belvedere, the butler is always the serious one. Geoffrey, who takes care of Will Smith and his family in their California mansion, felt like a throwback even when the show was on in the 1990s. Mr. Belvedere, which premiered in 1985, five years before The Fresh Prince came out, is about an English butler who ends up becoming a housekeeper for a family in the suburbs. It’s your typical fish out of water, silly 1980s premise, but somehow the show — based off a 1947 novel, Belvedere, by Gwen Davenport — ended up being one of the best and most beloved sitcoms of the Reagan era, and it’s all thanks to the butler. (Also Bob Uker, but mostly the butler.)

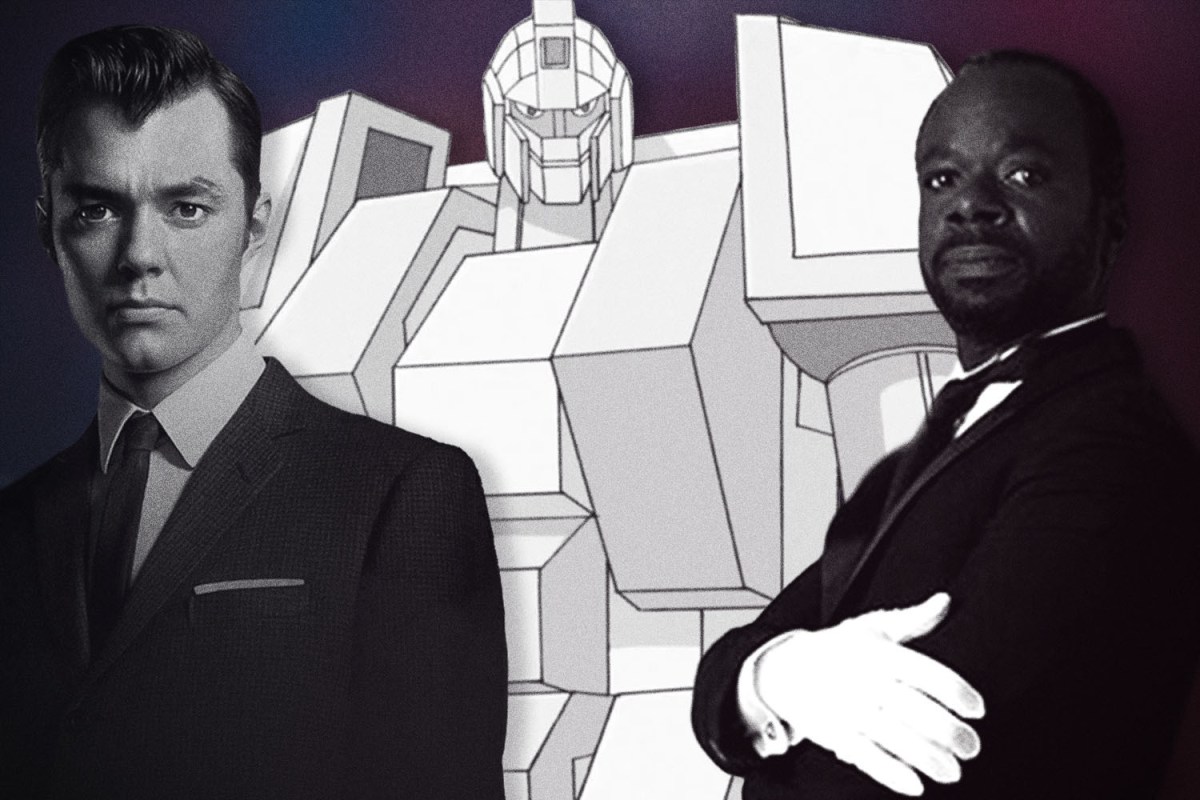

The closest thing we have to an interesting take on the fictional English butler these days is from comics. There’s the Stark family butler, Jarvis, who pops up in a few MCU tales, and there’s Pennyworth, the Epix show that tells the backstory of Bruce Wayne’s butler, right-hand man, confidant and father-figure, Alfred. The butler’s history in the Batman timeline is a little muddled: he started out as a chubby detective with a Cockney accent in the early-1940s, then had a reboot of sorts, showing up to work for Wayne as a butler. In many ways, Alfred set the template for a favorite sub-trope of mine, since his biography includes time as an intelligence agent: the English butler with a secret past. The best of these, in my opinion, is Tim Curry as Wadsworth in the 1985 film version of Clue. (Though, depending on which of the movie’s three endings you choose to accept, he could either be an FBI agent or the bad guy.)

If you’re looking for a fresh take on the English butler, the best one you’ll find comes from Neo Yokio, the anime series created by Ezra Koenig of the band Vampire Weekend. Voiced by Jude Law, Charles is the robotic butler of the show’s protagonist, Kaz. Here, again, we see the old idea that the servant is wiser than the person they serve, with Kaz letting his spoiled, impetuous side lead him to make bad decisions. I won’t say it’s the best thing about one of my favorite shows that has premiered on Netflix, but I can admit that if there wasn’t an English butler, even a robotic one, I might not have been as interested.

While the English butler continues to pop up in stories from time to time, it’s hard to imagine anybody trying to do what Ishiguro did with his book in 1989, or Wodehouse did before him. The English butler, sadly, will most likely remain a secondary character in period dramas on PBS and sometimes get occasional screentime in a comic book adaptation of some superhero story. It’s a shame, really, because what the butler knows almost always makes for the most interesting story.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.