We left the middle of the 20th century behind decades ago, but the aesthetic of the time has remained a presence in countless ways — from the continued impact of mid-century modern furniture to the evocative fashion worn by people of the period. When considering that enduring look, it’s also worth discussing the people who brought that aesthetic into focus — literally, in some cases.

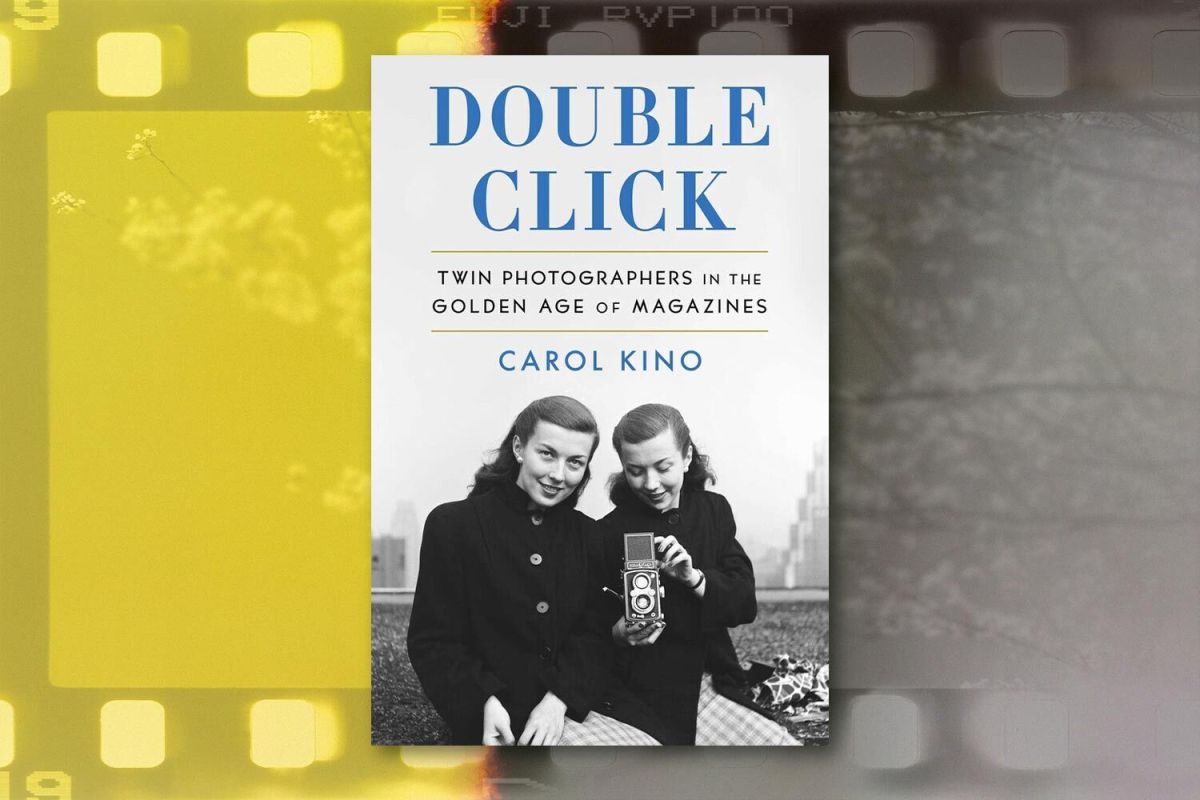

In her new book Double Click: Twin Photographers in the Golden Age of Magazines, Carol Kino tells the story of twin sisters Frances and Kathryn McLaughlin, who made names for themselves with their photographic skills, as their work was well-represented in the publications of the time. It’s a fascinating look at the middle ground between art and commerce, with numerous insights into how the sisters helped the form evolve.

Throughout Double Click, the twins’ paths overlap with a host of historical figures, from Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr. of the Tuskegee Airmen to F. Scott Fitzgerald. And some of the small details — including the post-World War II market for mass-market personal airplanes — make this trip back in time rewarding in some unexpected ways. Kino spoke with InsideHook about the book’s genesis, why the twins’ story remains relevant today and the archival research needed to make Double Click a reality.

InsideHook: Double Click opens with the McLaughlin twins being interviewed by Dick Cavett and being given comparable treatment to the likes of Toni Morrison and Federico Fellini. Both of those artists are still revered today, while the twins are likely not as familiar to readers in 2024. How did you first come to encounter their work and decide that they would be good subjects for a book?

Carol Kino: I have a friend who’s a publicist, and she works with a lot of photography galleries. So she told me about a show involving one of the twins, Franny or Frances, and her husband. It was a show of their work and their contemporaries, who were people like Man Ray, Erwin Blumenfeld and André Kertész. She convinced me to write about the show, and she also told me that there was a twin, and the whole family were photographers. So I wrote a couple of stories about that show.

Then at the opening, there was a small gallery devoted to family photos, and I just became completely entranced since they were all photographers. The photos were fantastic. They were also friends with Irving Penn and his wife Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn, so there were a lot of photos of the Penns, photos that Lisa had taken of them. In that show, I met the son of one of the photographers who told me his grandfather had been a famous photographer.

It just seemed like a great story, first of all. Then while researching the original stories, I discovered that there had been many photographer couples during this period, which was fascinating to me — and sometimes the women had been more successful than the men. That also seemed really interesting, too — that they’d been successful and we didn’t know about them today.

Besides the photographers who you mentioned just now, Diane Arbus shows up in the narrative, Gordon Parks has a brief appearance towards the end — there’s this dizzying array of important figures in photography throughout the book.

It was also this really interesting period when European refugees were flooding into America. Americans were already trying to figure out what American art is going to be in relation to Europe. Europe had always dominated America. But Americans in painting and in photography were trying to determine what is an American art, and then these European refugees were arriving, so they were trying to figure this out, too. That was so interesting to me because I’m first-generation American, so I grew up trying to figure out, what’s a real American? I was kind of intrigued by all of these Europeans and Americans asking this question at the same time.

The subtitle of your books uses the phrase “the golden age of magazines.” How did you determine what that timeframe was going to be like?

I think we kind of massaged the “golden age” for the purposes of the book. I think it’s debatable what the golden age was. It’s probably not right now, with magazines shutting down, but it’s debatable. I think there are exciting things happening on the web.

I read so many magazines for this book and it was such an exciting time when photography started being introduced into these magazines and there was a different visual look to every issue. Things weren’t art-directed to the hilt. You could do something different every month. Photographers were allowed to take their own creative course. So I guess I think the golden age also went on into the 1950s and the 1960s. But it was really particularly creative during this 1930s, 1940s and early 1950s phase, I would say.

If I remember my art history somewhat correctly, in the second half of the 20th century, there was a fairly sizable sea change where photography began being viewed more as an art form in and of itself. Do you think if that had been more of an option earlier, the McLaughlin twins might have been somewhat better known? If they had had more opportunities to explore the fine art world?

Yeah, maybe. I think it was the 1970s when it started becoming perceived as an art form. I think they were always thinking about art, but I don’t think they necessarily expected what they did to become art. I think fashion photography as art happened quite a bit later, so I don’t know that they would have made the case for themselves making art.

Franny, the one who worked at Condé Nast, developed dementia. So at the time that fashion photography started becoming considered art, she wasn’t in a position to promote her own work. I think that’s why she kind of missed the boat of being considered a great artist — which I think one could make the case that she is.

One Photographer’s Trip Into Punk History

Jim Saah’s “In My Eyes” features photos of artists ranging from Foo Fighters to Minor ThreatIn the acknowledgements for Double Click, you thanked a lot of members of their families and extended families. Were the families all very supportive of the project?

Yes, they were all into it. They didn’t always move at the same pace. I mean, I find when you’re writing journalism, people do call you back pretty quickly. When you’re writing a book — this is not necessarily the family — but I found people often say things like, “Oh yeah, when I go through my attic next summer, if I happen to find those pictures, I’ll get back to you.” So a lot of those people I had to give up on. Everything moves at a slower pace when you’re working on a book.

Kathryn’s family, the Abbes, amazingly gave me the key to their storage space. I was going there with Kathryn’s assistant, Chris. I went there with him in the beginning, and then they let me go there by myself, which was great because there were so many newspaper clippings that I needed to look at in detail, and it was hard to do that when I was chatting with Chris, who’s a really fun person.

The other twin’s archives are still in her apartment, and her grandson lives with them, so it wasn’t as accessible. But, yeah, they made it relatively easy for me to get at everything.

Were most of the archives you were going through familial and personal collections, or were you also going into magazine and newspaper archives?

I had a fellowship at the New York Public Library, a Cullman Fellowship, and not everything was there, remarkably, but the librarians there really helped me. One of the things that I needed to find was the first teen or college magazine, which was College Bazaar. A lot of the magazines had not been digitized, so I had to page through them and scan them for my own reference.

Mademoiselle and Charm are in the New York Public Library, not digitized. Glamour they did not have, so I had to go to the Condé Nast archives for that. I paged through 15 years’ worth of magazines for each of those, I think, which was really overwhelming. But College Bazaar did not exist — anywhere — and that was a real problem that the librarians at the New York Public Library helped me solve. We eventually found it in a library miscatalogued. It was just incredible.

The twins studied at Pratt, which turned out to have had one of the first photo labs in a school in America. I thought I would go to Pratt and say, “So tell me when it started.” And they said, “You’re welcome to go through all the school newspapers” — which had not been digitized at that point. “You’re welcome to go through all the school catalogs. You’re welcome to go through the faculty minutes.” I kept coming up against these subjects that nobody happened to have studied. I was just so depressing and daunting. I had this iPhone that I digitized all of those things with.

Then I’d call up photo historians and say, “Do you know the history of Pratt?” And they’d say, “Isn’t that interesting? Nobody’s studied that. Isn’t that fascinating?” There was no way to go but forward if I wanted to fulfill my contract and write the book.

You mention in Double Click there was a magazine that was for winners of the contest to find the most talented college students. I was just amazed that there was a magazine with this very limited, very specific audience.

I think that was Smart Girl. I discovered that really early on by going to the Condé Nast archives. I had done research into the Prix de Paris, which was this famous prize that Vogue did. I think it started in 1935. It was a great competition.

There were lots of competitions for college-age girls at that time. The Prix de Paris was the grande dame of all these competitions. Joan Didion did it. Sylvia Plath. I think Ann Beattie did it. A lot of people. Meg Wolitzer, I think. I get it mixed up because Mademoiselle had these competitions, too. But I think that was the one. Jackie Kennedy — Jackie Bouvier at the time.

The person who was managing the archives had done research into that for her master’s thesis, I think. I don’t think anyone had looked at it since then. So in these archives, I discovered this magazine called Smart Girl. I just discovered several issues of this magazine and digitized them with my trusty iPhone, and there was tons of really interesting information in there.

Some of the other details that you share in the book about post-World War II society really floored me. I had no idea that there was a consumer market for private airplanes for commuters, for instance.

All of this military equipment was being sold in department stores. Jeeps. Not guns, but other, more domestic kinds of equipment. I think Macy’s seventh floor had the airplane department. So the elevator operators would say, “Ladies’ lingerie, planes,” which was so wonderful.

It was this plane that steered like a car. I think they’d been developing it before the war, but then resources had to be diverted to the military. Then, after the war, there was all this money. America wasn’t in a depression mode anymore. Kathryn, the other twin, saved up her money during the war and bought her husband an engagement present of a plane. She said that’s why he married her. So they had a plane to fly between Montauk and all of their different jobs.

There are also eerie echoes of the present day when you mention that, during that period, the marriage rate was going down in part because people had concerns over money. That felt very familiar.

Yeah, didn’t so much of it seem like today? I thought it was so relevant. And those essays by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s daughter — I loved that essay where she says, “Our profligate Jazz Age parents just don’t know the score, but we do.” She sounded like somebody complaining about her lousy Boomer parents. I just love that part.

You said you wrote a little bit about the sisters before starting work on this book. How much of this milieu were you aware of initially and how much did you have to discover on your own?

A lot of it was discovery on my own. In retrospect, it’s really interesting. As I was doing it, it was kind of painful because there was so much detective work. When I first met Kathryn’s youngest son, he actually turned out to live about 15 minutes away from my parents in California. Later on his mother became a very well-known photographer of children and he had these Better Homes and Gardens baby books that both twins had worked on. I couldn’t believe that his mother had photographed a lot of famous pharmaceutical ads that I’d seen growing up. I couldn’t believe how influential — I mean, those ads were part of my childhood — I just couldn’t believe the important role they played in society without me having been aware of it.

As you mentioned towards the end of the book, there have been periodic upticks in interest in the twins. Is there a hope that this book will also spark another revival and pique more interest in their work as well?

Definitely. I hope that it does. It seems to me that it’s kind of a missed opportunity if it doesn’t. I think it should, especially for the women who did not get any of the recognition that’s due to them.

It was also very interesting, as you pointed out a few times, that they were from much more of a working-class background than a lot of their peers.

They really did come along at a time when the aristocrats had been taking photographs — or people who added aristocratic names to or used their title as photographers. It was a moment when the career girl was being celebrated and these were genuine career girls, who took the subway to work every day, which was not the case for the female photographers who’d come before them.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.