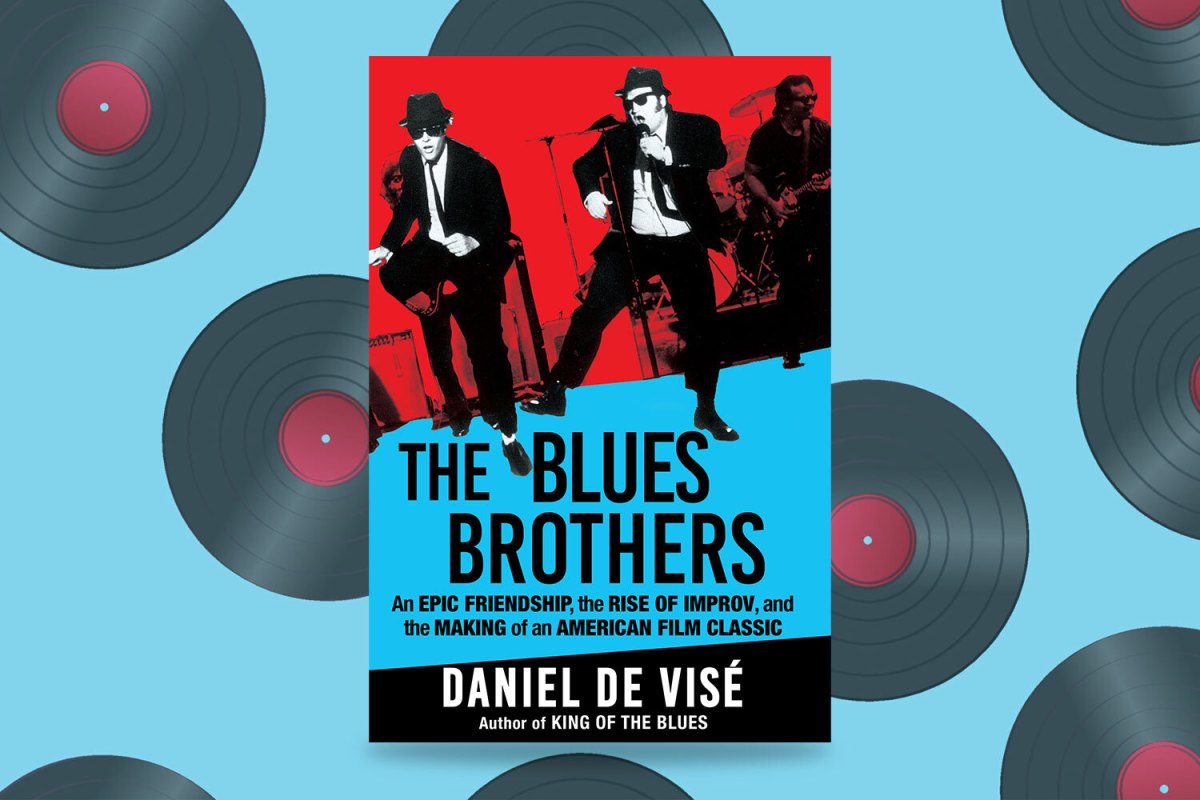

There’s a singular place where the histories of comedy, music and film all converge, and its name is The Blues Brothers. Saturday Night Live castmates John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd started a band to tap into the music that they loved, one that became wildly popular and led to a now-classic film that debuted in 1980. In his new book, The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic, Daniel de Visé explores the lives of both Aykroyd and Belushi, the music they made and the chaotic production of the film The Blues Brothers. It’s a fascinating look at the evolution of two comic geniuses and the birth of their unlikely musical collaboration. InsideHook spoke with de Visé about the book’s origins, the film’s legacy and what some decades-old VHS tapes have to do with it all.

InsideHook: In the acknowledgments of the book, you talk about its origins coming from a stack of VHS tapes you’ve had for a while. Can you tell me a little bit more about the origin story of this book and what those tapes have to do with all of it?

Daniel de Visé: In probably bold defiance of piracy laws, when I was 13 or 14, I had a shelf or two of treasured VHS tapes. I would rent VHS tapes from a wonderful video store around the corner from my pop’s house, which is in the Lakeview neighborhood of Chicago. And I would watch the film, I’d pay for the rental, I’d bootleg it. And I ended up with 20 or 30 of my favorite movies that I just kept bootlegs of.

I interviewed John Landis for my last book, which was about BB King. And the reason I interviewed John Landis was, I wanted to know why BB King wasn’t in The Blues Brothers film. I got to know John Landis in that book. And I got to talk about these movies, and I said, “I had maybe 25 or 30 of these movies, and five of them were John Landis films. Kentucky Fried Movie, Animal House, Blues Brothers, An American Werewolf in London and Trading Places. I may be missing a couple, but that was basically the core.” And he was impressed that I was a real fan. And so that plus talking to him inspired this book.

Also in the acknowledgements, you thanked Dan Aykroyd and Judy Belushi for opening some doors for you. Were you concerned when you started this project about how much access you were going to get? Was there anyone who you weren’t able to talk to who you would have liked to chat with for this?

I’ve done five books, and I’m always terrified about access. Always. There’s never been a book where I haven’t been, going back to the Andy Griffith and Don Knotts book I wrote several years ago. With this book, was I going to get to talk to The Blues Brothers band? Was I going to get to interview Landis? He seemed to be really friendly, but would he really help me? And all of his crew, you know, would they fall into line?

With every one of these books — this is the good news — it fell together. In the end, I got almost everybody I wanted. So for the part of the book about The Blues Brothers, which is the most important part, I got pretty much everybody. I mean, obviously I wasn’t able to talk to John Belushi, but I was able to talk to Aykroyd. I talked to Landis for dozens of hours over the course of months. I talked to his top people, I interviewed them over and over. I talked to just about every living member of The Blues Brothers band that performed in the film.

Dan Aykroyd made himself available, which was great because he didn’t have to at the beginning of the project. You probably know how Hollywood works. They weren’t attached to this project. In Hollywood lingo, it wasn’t an official Blues Brothers project as a branded Blues Brothers thing. And for that reason, at the beginning, they said, “I’m so sorry, you know, we really want this to work. We’d love for you to see this come to fruition, but we can’t really work with you.” But in spite of that fact, Aykroyd not only granted me one long interview but also was there to answer goofy questions, like when I wanted to know how many miles he walked to and from school in Ottawa.

And Judy Belushi, God bless her, at every turn, when somebody went to her and asked, she always said, as far as I know, “Please talk to him. He means no harm to your planet.”

Was it a challenge to balance writing about Belushi and Aykroyd’s history before working together versus the making of The Blues Brothers? Were you concerned about finding the right balance between those different elements?

Absolutely. It wasn’t just a fear of mine. My editor, and my literary agent were worried about what I was doing because I didn’t follow the formula one normally follows in writing a book about a film. Usually, a book about a film is mostly about the film. I did not want to do that. I wanted to consciously follow the exact same formula I followed with Andy and Don, which is my book about Andy Griffith and Don Knotts. That book is my greatest hit, singular. It’s the one book I’ve written that sold big, big numbers, and I’m still getting like, four-figure royalty checks twice a year for it several years later.

The formula is this is a dual biography. It’s a biography of Aykroyd, it’s a biography of Belushi — modest ones, not hundreds of pages, but a real biography of each of them. And then where they intersect, once they meet, it becomes a story of the two of them and their friendship, this wonderful, wonderful friendship of these two guys. And then it follows them through everything in this arc that leads us up to The Blues Brothers, which I would say was probably the greatest thing they did. In the case of Andy and Don, it ends when Andy and Don die, which is decades after The Andy Griffith Show. But in the case of this book, I didn’t actually know where it was going to end. I literally didn’t know until I stopped writing. But I stopped writing after Belushi died. His memorial ended up being the last scene.

Something about The Blues Brothers seems relatively unique in that they began in a comedy context and became a legitimate rock band. I loved the movie Popstar, but I can’t imagine the Lonely Island going on tour as those characters, for example. Did you see any other precedent for what The Blues Brothers did? Or do you think this is a case of lightning in a bottle?

There are so many frustrated musicians out there in the world of actors and comedians. And I think of some of the big names in Hollywood who’ve had bands, Kevin Bacon is one. Billy Bob Thornton, who I interviewed for Andy and Don, I think he’s another. There’s a bunch of cases. I ran into Keanu Reeves once in a practice room in Hollywood. When I lived out there, I was in a band, he was in a band, and we were just these two dudes walking past each other in a practice space.

In terms of The Blues Brothers, I think it was kind of unprecedented to have these two guys who are TV stars basically dream up this band, make it real, enlist this all-star backing band and then go on a massive tour and get serious reviews and serious newspaper coverage where that became their lives for a couple of years.

If you think of it in the context, it would be like two famous performers creating a stage show — like if Steve Martin and Martin Short went out and did this stage show and it just happened to be a series of musical concerts. Like going on Broadway, you know? And remember, Belushi had done that by joining Lemmings. He basically went from being one of many people who passed through Second City, albeit a very successful one, in Chicago to being in the cast of this thing. What was it exactly? It was a musical. It was a rock concert. It was a send up of Woodstock. It was weird. And maybe that was what gave him the idea.

Did anything come up in your research about either of your subjects or about the making of The Blues Brothers that left you surprised?

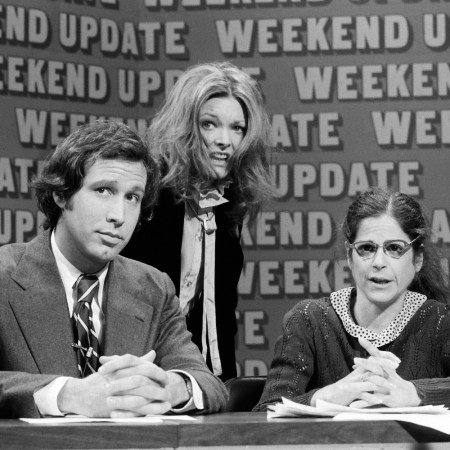

I thought I knew SNL pretty well. And I thought I knew Second City by extension fairly well. But I was still stunned at the singular magnificence of the Second City Toronto troupe, the original one. This would be the one, of course, that during a very short period of time featured Catherine O’Hara, Eugene Levy, Joe Flaherty, Dan Aykroyd, John Candy, Gilda Radner and Rosemary Radcliffe.

In terms of the movie, I didn’t realize how much of it wasn’t even shot in Chicago. I guess I could have figured out some of it wasn’t. If I thought really hard, I could have realized that some of the interiors were shot on a soundstage. That makes sense. But the tunnel scene with Carrie Fisher with the machine gun that was shot not in Chicago in a dank tunnel — it was shot on a soundstage. The Nazis going off the bridge, that scene was shot in something like 20 different places. But the actual bridge to nowhere was in Milwaukee. And it’s still really well known; people in Milwaukee really embrace their piece of this film.

I found the details about the mayor of Chicago’s role in the making of this film to be fascinating as well.

What I think happened — and Chris Borrelli at Chicago Tribune would probably know more about this — was Jane Byrne was reviled by all of Mayor Daley’s cronies, these aging guys who were in power in Chicago. They were sexist and misogynist and called her all sorts of horrible names. Mayor Byrne, I think, relished the idea of having a film crew smash through the Richard J. Daley Plaza. A little bit of comeuppance and a little bit of vindication after being bruised and battered by his people since she’d taken office. I think she was pretty damned excited about that.

You also brought up the Pope’s visit to Chicago while the filming was underway, which sounds like a case of truth being stranger than fiction.

There’s a picture in my book of a fake Pope who met the cast and crew as a joke. Landis, who’s hilarious, thought it would be hilarious to have them think they were meeting the real Pope. And so the Catholics on the crew hit the dirt when the Pope showed up, but it turned out he’s a fake Pope. That picture circulates from time to time, and it’ll have a caption saying it’s the real Pope.

What We Learned From the New Documentary “Belushi”

Garage bands, a Nixon connection and Gene Shalit all play a partEarlier, you talked about The Blues Brothers being a cult film for you growing up. Do you feel like that aspect of it has endured, or do you think it’s a situation where that’s true for viewers in their 30s, 40s and 50s but less the case for a younger generation?

I would say it’s one of a small but ever-growing number of films that get referenced a lot in popular culture. I guess that that goes back to Gone With the Wind, Casablanca and The Wizard of Oz. I grew up in Chicago in the ’70s and ’80s, so the films I could probably quote from, other than The Blues Brothers, were Spinal Tap and Monty Python and the Holy Grail. If I were a bit younger and hipper, then [it would be] The Big Lebowski or maybe Superbad or Dazed and Confused. And that’s kind of a guy list. My friend Jennifer Keishin Armstrong just wrote a book [So Fetch] that I can’t wait to read about Mean Girls. And that would be one that a lot of female viewers would probably be able to quote lines from. In terms of The Blues Brothers, I think a lot of guys of a certain age have seen the film a sick number of times. I’m counting on their dollars.

Unfortunately, the rise of Nazis, again, has made the “I hate Illinois Nazis” line a little bit more contemporary than the people involved with the film would have ever liked.

Even though there’s this huge issue of cultural appropriation attendant to The Blues Brothers — the idea of these white guys leading this film and leading this band was heavily attacked at the time. So that’s not new. But in spite of that fact, I would argue the film has aged pretty well. There’s no gratuitous nudity at all. The musical performances just seem to get bigger and bigger with each passing year. And that was where the point of the movie, to showcase Aretha Franklin and James Brown and John Lee Hooker. And those just get more and more resonant over time, so I think the film’s aged pretty damn well.

I’m glad you brought that up because I’d been meaning to ask about the cultural appropriation question, both now and when the film first came out.

I was happy to see the issue was thoroughly aired when the film came out, even before the film came out, especially in the alternative press and in the pages of Rolling Stone. A lot of young, white, male writers said the band was almost racist: how dare these white comedians go out and play a bunch of Black rhythm and blues music with a mostly white band?

The Blues Brothers were attacked at the time. And rightly so on many levels. But their whole point was to showcase this music they loved. And why should they be attacked for that? Well, you can read the book and figure out where you stand. But I’ll say this, and I say this in the book — in the end, there was going to be a Blues Brothers movie. No matter what, it was going to happen because they were so popular, especially Belushi. And they couldn’t do that movie without it starring the Blues Brothers. Thankfully, the movie became essentially a showcase for these wonderful rhythm and blues artists. And those performances are remembered as well as any other scene in the film. I think that’s the film’s enduring legacy.

The one other thing I’m going to say is that when I first saw that film, I went out and bought, not The Blues Brothers soundtrack, but The Best of Sam and Dave. And I think that’s what Aykroyd and Belushi would have wanted.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.