“It always brought joy.”

That’s Eames Institute Chief Curator Llisa Demetrios discussing the work of the institute’s namesakes — and her grandparents — Charles and Ray Eames. The occasion for our conversation is the release of a new online exhibit, Steinberg Meets the Eameses, along with a catalog of the same name. Both exhibit and catalog document a fruitful overlap of creative interests — namely, the work that Charles and Ray did with illustrator Saul Steinberg, and the creations that their meetings inspired.

As Francesca Pellicciari’s informative catalog essay explains, Steinberg, a frequent New Yorker contributor, met the Eameses through mutual friends in California, which soon led to both personal friendship and creative collaborations. These included more ephemeral works, like illustrations projected onto Ray Eames and artist (and Steinberg’s wife) Hedda Sterne, as well as a notable pair of Steinberg drawings on two Eames chairs. One featured a slumbering cat; the other, a nude female form.

“For me and for us at the Institute, [the project started] because there was going to be a limited edition of the chair with the cat in it, coming out with Vitra and Herman Miller,” Demetrios told InsideHook. “I had always loved the pieces of Steinberg that we have. And so it seemed like a great opportunity to highlight those from the collection.”

Demetrios went on to point out the different ways in which the Steinberg-Eames friendship influenced all of the parties involved. “From that meeting in 1950, you can see the connection with Steinberg in Traveling Boy, the short film,” she said. “Some of the scenery is part of Steinberg’s work.”

Looking at the work of Steinberg and the Eameses in isolation, there isn’t necessarily a lot of aesthetic common ground. Demetrios has a theory as to why they ended up clicking so well when working together.

“There’s an expression that Ray and Charles used, which was, ‘Take your pleasure seriously.’ I would say that applies to all three of them,” she said. “That means that you really know your craft, you know what you’re making, but you also are enjoying it.”

The catalog notes that the drawing of a nude woman has sparked some controversy over the years, though it’s hard to imagine anyone ever considering the stylized illustration anywhere remotely close to explicit. There is one way in which its current condition differs from how it was originally drawn. As Demetrios explained, “At that time, the drawing of the woman went all the way to the floor, onto the concrete. I wish we had the concrete, too.”

She went on to describe how the chair with the image of a sleeping cat remains especially popular. (The recently reproduced run of 500 chairs from Vitra and Herman Miller quickly sold out.) That has to do with its place in both design and illustration history.

“In the collection at the Eames Institute, we have several pieces that do go out on loan quite a bit. And this is one of them, because the chair is an early version,” she said. “And then you have Steinberg’s drawing on it. It just has so many great layers to it.”

The illustrated chairs are not the only places where Demitrious finds that lessons in art and aesthetics can be gleaned from the work contained in the exhibit. “You get insights from looking at how a chair is made with Ray and Charles — or how a film is made — as there are layers to it,” she said. “The same is true with Steinberg.”

Demetrios cited the example of a particular commission to demonstrate this concept. “There’s the machine that they made called the Solar Do-Nothing Machine. [The Alcoa Corporation] reached out to about 20 architects and designers and said, ‘What can you make with this new material called aluminum?’ Ray and Charles made this wonderful machine that does absolutely nothing fabulously.

“But the real message is when you watch it twirl and spin and do all kinds of things, at the very last moment, you realize it’s being run by a solar panel. And it’s really Ray and Charles’s opportunity to share that there are alternatives to fossil fuels.”

Demetrios’s work as both a curator and a descendant of Charles and Ray Eames gives her a particularly personal stake in this exhibit — and it’s also shaped the way in which she views some of the work contained in it.

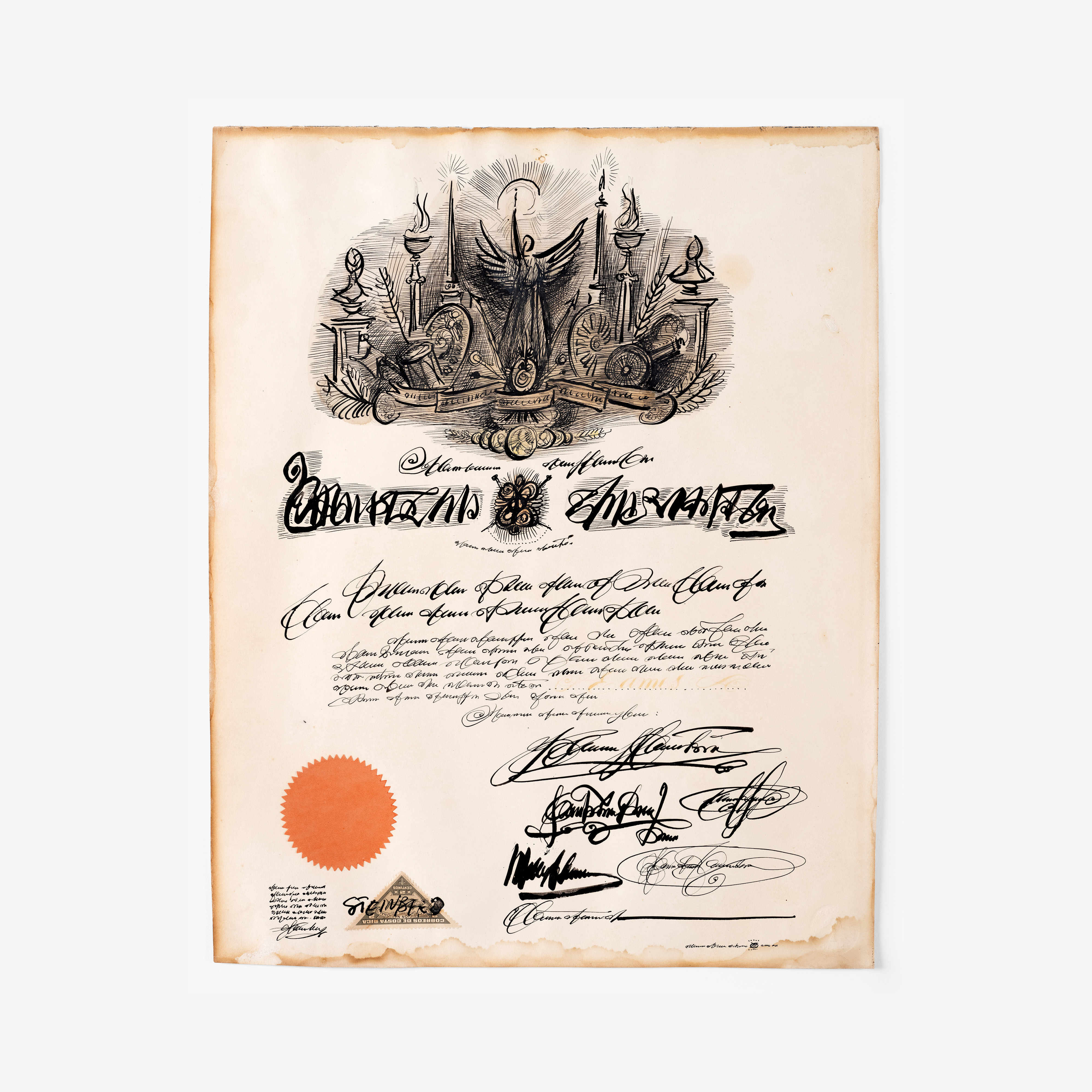

“For me, what’s also just really special was revisiting the diplomas. I think you might know the story that Charles did not finish architecture school. He was asked to leave before he finished,” she explained. “When Steinberg heard about that, he made Charles three or four fake diplomas. So growing up and seeing these diplomas around — there was one at the house, there were a couple at the office, and we have two of them here in the collection today — they looked real. They look very formal.”

“You’re looking at this, and that looks like an official document,” she added. “But then to have Ray and Charles have me look at it closer and realize there’s nothing said in the writing or anything — that was just marvelous because it added a wonderful layer to that artwork to me. That was the playfulness but also the seriousness of what Steinberg had made.”

That, then, speaks to the wider view of revisiting some of these works of design history. “For me, it’s always so fascinating to see something as a grandchild and then just look at it again as a curator,” Demetrios said.

And for her, the work contained within Steinberg Meets the Eameses is also an occasion to revisit childhood memories.

“I remember seeing those as a grandchild visiting the office and just seeing the beautiful designs of my grandparents with the very beautiful ideas of Steinberg,” she said. And with this exhibit, those same designs are brought together for contemporary viewers to savor — and potentially be inspired.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.