Five books, released over the course of 46 years. By that measure, the bibliography of the late Charles Portis — who died on Monday at the age of 86 — was far from huge, especially considering his influence in American literature. Most writers of Portis’s stature could fill shelves in a library: you’d have to be an obsessive fan or a scholar to know all of Mark Twain’s works; Philip Roth’s “Zuckerman” novels alone nearly outnumber Portis’s published books; Toni Morrison put out nearly a dozen novels to go along with her children’s books and collected non-fiction, not to mention her work as an editor, two plays and a libretto. With Portis, we have six books left to remember him by. Five novels, one collection of shorter work.

And yet — those are all books with their champions, who would fight tooth and nail to defend the honor and relevance of their preferred book of Portis’s. That Portis’s own work could generate the sort of enthusiasm bordering on the absurd that fueled so many of Portis’s characters is both ironic and deeply fitting. As more than a few of his admirers have pointed out, Portis’s work lines up uncannily with the present day — but that’s less a case of it being ahead of its time and more about it being timeless.

Given its pair of high-profile film adaptations, it’s not surprising that True Grit is the first book that comes to mind when referencing Portis. “I cannot think of another novel — any novel — that is so delightful to so many disparate age groups and literary tastes,” wrote Donna Tartt in her introduction to a 2005 edition of the novel.

That’s a quality that can be found in his other works as well, albeit in different forms. Some very funny people — including Bob Odenkirk and Bill Hader — have professed their fondness for Portis’s writing, for one thing. In their announcement of an event celebrating the 50th anniversary of Norwood, The Oxford American noted that ”it continues to delight a half-century later.”

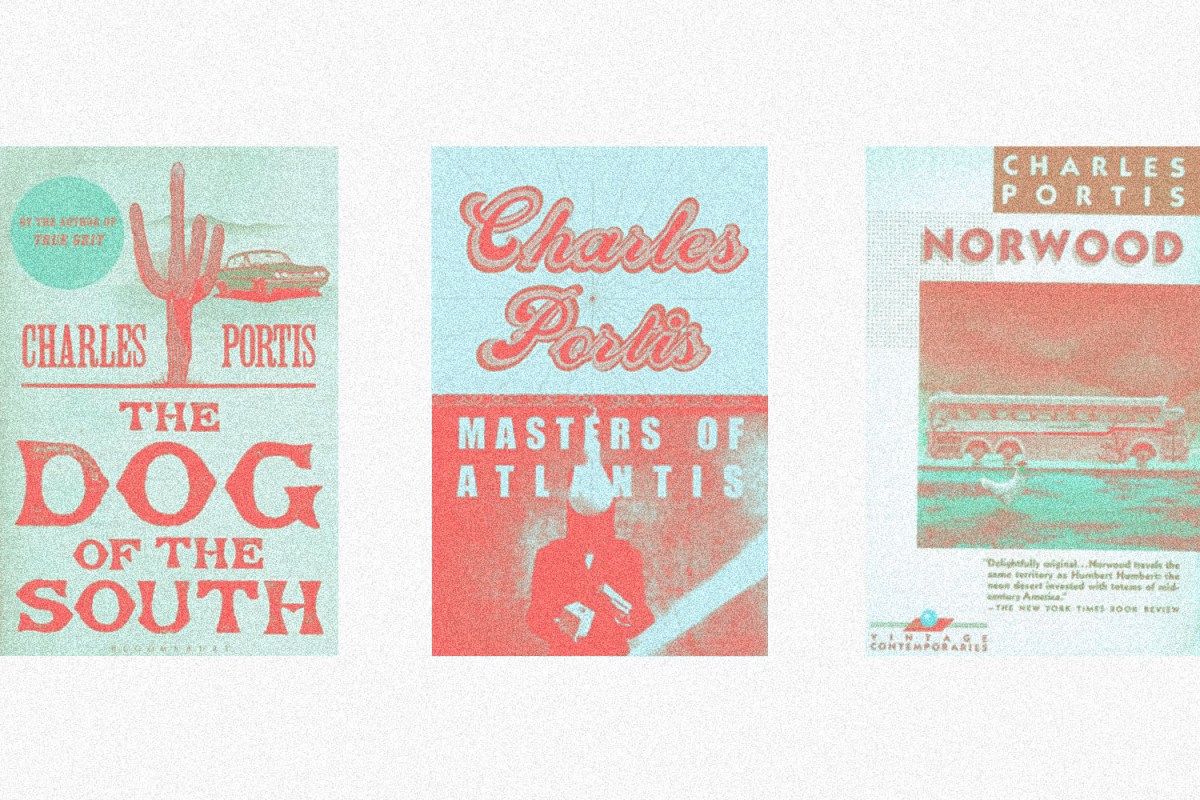

Writing about Portis’s novel The Dog of the South for The Ringer, Elizabeth Nelson neatly summarized the work of this most difficult-to-summarize of writers. “Portis’s protagonists operate at a peculiar frequency and are typically driven to drastic measures by events outside of their own control,” wrote Nelson — and while that does suggest certain ineffable qualities, it also helps to explain why Portis’s work continues to resonate.

Nelson also alludes to some of the stranger elements of Portis’s work when describing one particular scene from The Dog of the South: “It is also emblematic of the other ontological track on which The Dog of the South and much of Portis’s other work operates: the sub-rosa, the mystical, the conspiracy-minded, and the apocalyptic.”

Portis’s novel Masters of Atlantis — about secret societies, a turbulent nation and warring factions of true believers — spans decades and plays out both like a secret history of the middle of the 20th century and an allegory for any number of things in American life. Here, too, is one of Portis’s talents: the ability to blend timeless allegory with a disquieting specificity.

As alluded to earlier, there are few careers that resemble Portis’s. But while the two are very different in their prose, in their subjects and in their work, one can find more than a few resonances between Portis’s work and the books of Marilynne Robinson. Both have looked to society’s outcasts to discover something essential about that society; both have found devoted readers from idiosyncratic subjects. And both understand well that an ambitious novel can exist within a modest set of pages.

In both, too, can be found a search for the sacred — though the quests of many of Portis’s characters took them to the last places one might expect. Portis’s work creates its own rhythms, never stopping for a long enough time to be pinned down. He rarely gave interviews, but Portis’s work achieves an oracular status. Sometimes, a handful of books is all you need to speak volumes.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.