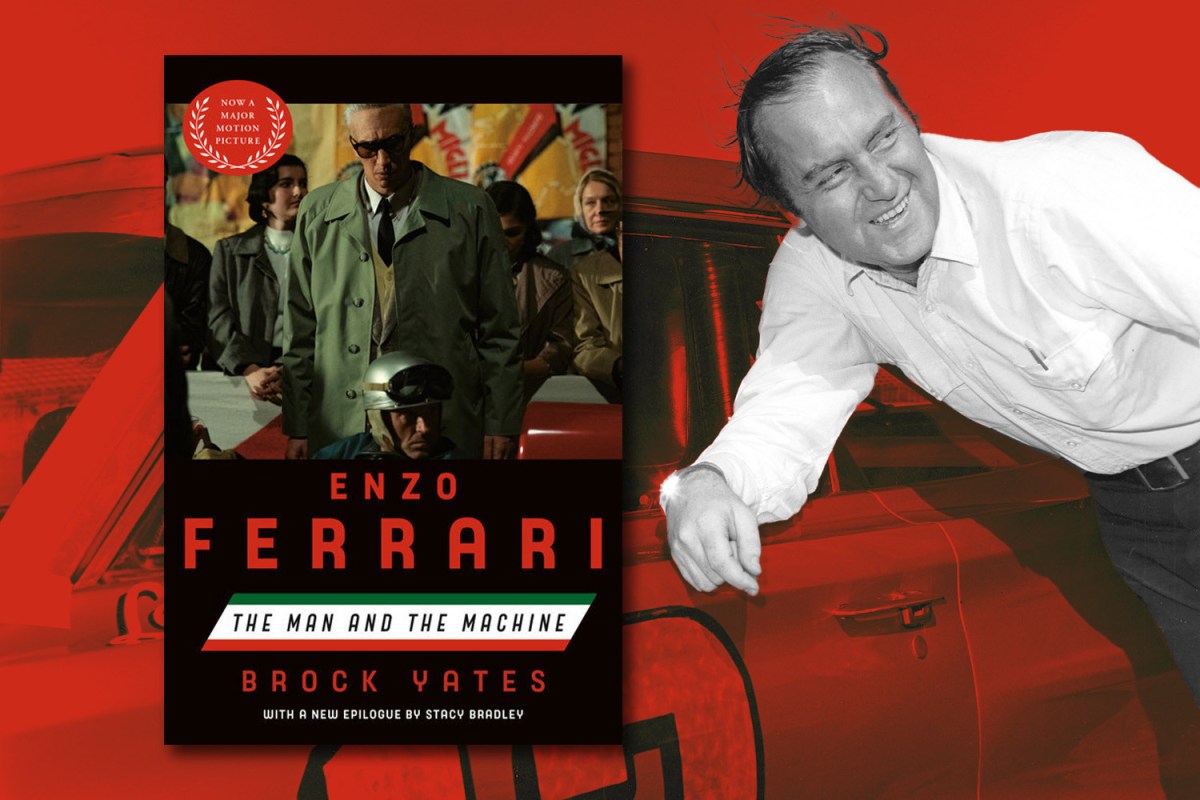

Every story has a starting line — some more literal than others. Since the release of director Michael Mann’s Ferrari, much has been written about the filmmaker’s long road to getting the film made. You can get a sense of that from a cursory look at the credits: the film’s screenwriter, Troy Kennedy Martin, died in 2009. You’ll need to go even further back for the publication date of the book Martin was adapting: Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine, a 1991 biography by the acclaimed writer Brock Yates.

Yates’s involvement with all things automotive went far beyond writing a detailed biography of one of the auto world’s most complex subjects. Yates is perhaps best-known for his role in creating the Cannonball Run — and for writing a book, Cannonball!, which tells the story of some of the personalities involved with the cross-country race in question.

Yates himself died in 2016 at the age of 82. Prior to his death, he worked with his daughter, Stacy Bradley, on a revised edition of Ferrari to coincide with the film’s release. As Bradley tells InsideHook, Yates had long sought to revise some of the text of the original biography in the years following its publication.

“Brock and I had spoken through the years after the original book was published in 1991,” Bradley says. “He wasn’t happy with the original book.”

Some of Yates’s issues with the 1991 edition, Bradley explains, were relatively specific to the milieu he was working in. “There were a lot of typos that made Brock’s brain explode and some big typos — you know, of race car drivers and engineers — things that were a big deal to Brock from an automotive standpoint,” she says.

Bradley recounts the evolution of her working process with her father — something that shifted over the years after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. “As he was gripped more and more with Alzheimer’s, he and I had talked about it a little bit here and there. He was losing more of himself, if you will, through the disease,” she says.

“He was still writing at that point, but I was more heavily editing his things than I had before. I’d been editing his work for years before the illness took hold and I was finding that the editing was becoming more complicated. Not that I couldn’t handle it — it just wasn’t up to what I had been used to my father writing,” she adds. “So we would sit and talk at length and I would get his perspective.”

In an interview with Bilge Ebiri for Vulture, Michael Mann recounted the early days of Ferrari, when he and Sydney Pollack — another towering figure who died years before Ferrari’s release — were initially working on the project in the 1990s. In talking with Bradley, she also shared that “the topic was initially broached not long after the original book came out and then it went away.”

“I would say Michael has been thinking about this for 20 years and we’ve been kind of pushing it along for the last 15 years. It’s been a very long road to get this movie made,” Bradley says. “Michael is extraordinary in his kind of myopic vision, if you will — and I don’t mean that in a critical way. He gets his teeth into something and you know, damn it, he’s going to do it. It’s pretty extraordinary when you think about the length of time that this book has rumbled around.”

The path to this adaptation of Yates’s book went through several casting changes; prior to Adam Driver’s casting, both Christian Bale and Hugh Jackman were associated with the lead role. Yates himself was aware of the project being — pardon the pun — back on track.

“I’m pleased that Brock knew before he passed that the movie was back in circulation in terms of the concept,” Bradley says. “That made him happy — especially when not much made him happy in the early days of his diagnosis.”

Reading Enzo Ferrari, one gets a good sense of Yates’s skills as a writer — specifically, his ability to write about the automotive world in a way that a layperson would understand. The book also accomplishes the difficult task of encapsulating its subject’s life for good and for ill. It also begs the question: where does Enzo Ferrari fit in Yates’s larger bibliography?

“Brock was an interesting writer in that he certainly got pigeonholed as an automotive journalist. But his degree was in history. He was a naval officer; his father was a writer for and then publisher for Science Digest very early on and had written quite a few books. His mother was a librarian,” Bradley says. “Writing was in his blood.”

Bradley also speaks highly of 1996’s The Critical Path: Inventing an Automobile and Reinventing a Corporation, describing it as “eviscerating on some levels of the American automotive industry and their myopic vision without being able to see past their own problems.”

“He would look at all aspects of the automotive industry, but he looked at it through the lens of history,” Bradley says.

“Ferrari” Stunt Director Robert Nagle Shares His High-Speed Secrets

To do an Enzo Ferrari biopic justice, Nagle’s bag of tricks included hand-hammered aluminum cars, Nick Mason’s Maserati and Patrick DempseyAs for where it stands in his bibliography, Bradley offered some insights there as well. “The Critical Path was very highly acclaimed. Ferrari, as I say in the foreword, was equal parts joyful for historians — and for acolytes of Ferrari, not so much,” she says. “They didn’t like seeing Ferrari, the real man. They wanted this persona that a lot of writers in the past had built up — Ferrari as this huge, flawless individual.”

Bradley also notes that Yates’s columns for Car and Driver showed off a different side of her father’s work. “His columns were more biting. He was nicknamed ‘The Assassin’ early on in his career — oddly enough, so was Ferrari — because he could be incredibly acerbic and didn’t pull his punches. His books were much more measured,” she says. “They weren’t biting. They were historic treatises on whatever topic he was dealing with. I wish, to a degree, some of his books had been a little bit more bitchy, if you will, because his columns were incredible. He had such an interesting voice.”

Bradley’s descriptions of Yates’s working methods may strike a chord for anyone with a fondness for in-depth recording. “If he didn’t know something he would get on the phone. If he didn’t know something he would travel for it,” she explains “My mother and he traveled at length for Enzo Ferrari — they were in Italy for a very long time.”

Given the breadth of Yates’s bibliography, I raise the question of what Bradley’s own favorites from there happened to be. “I do enjoy the Cannonball Run book because I know most of the people who turned in their stories,” she says. “My mother’s got an essay in there, my stepbrother’s got an essay in there. Bill Warner does. So many people that I grew up with are in Cannonball!, so for me it’s a sentimental book for me. I grew up with Cannonball!. I’m biased.”

Bradley’s fondness for Enzo Ferrari came from a different aspect of the book. “It’s something I got to work with my father on, and to me that was always something I’d wanted — that I can verifiably say that I worked on this with my father,” she says. “My name’s attached to it and his name’s attached to it.”

It’s another book that holds a close place to Bradley’s heart — Yates’s early book Sunday Driver: The Writer Meets the Road — At 175 MPH. “Sunday Driver is a great little book. It’s a first-person account of his racing career. Sunday Driver might be one of my favorites,” Bradley says “But if I were given three choices — for sentimentality, it would be Cannonball!. For one that’s always going to own my heart, it would be Enzo Ferrari, because I got to work with my dad. And Sunday Driver, in terms of the actual body of that book.”

It’s an impressive literary career — and if Yates’s book on Enzo Ferrari happens to be your first exposure to his work, there’s a lot more where that came from.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.