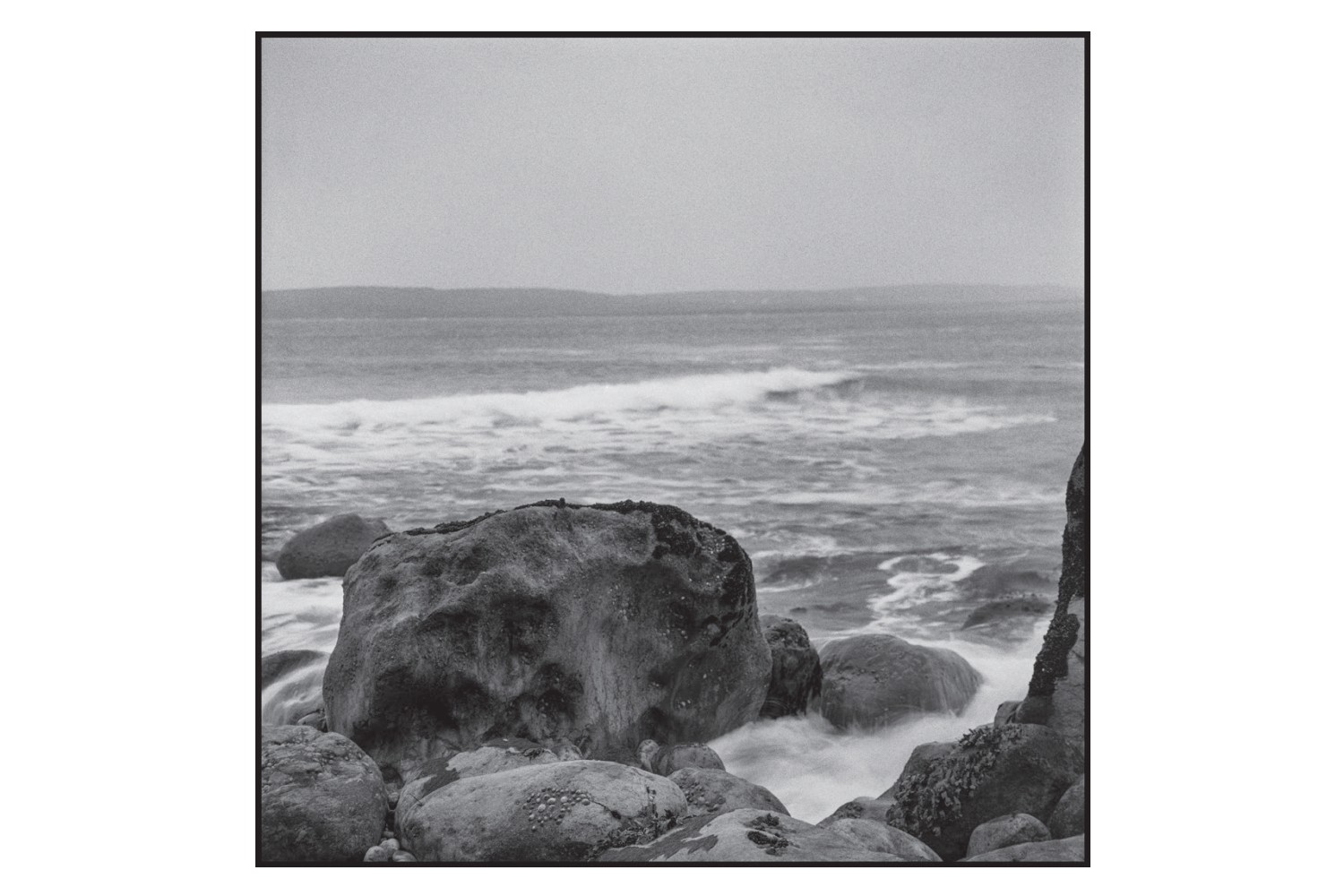

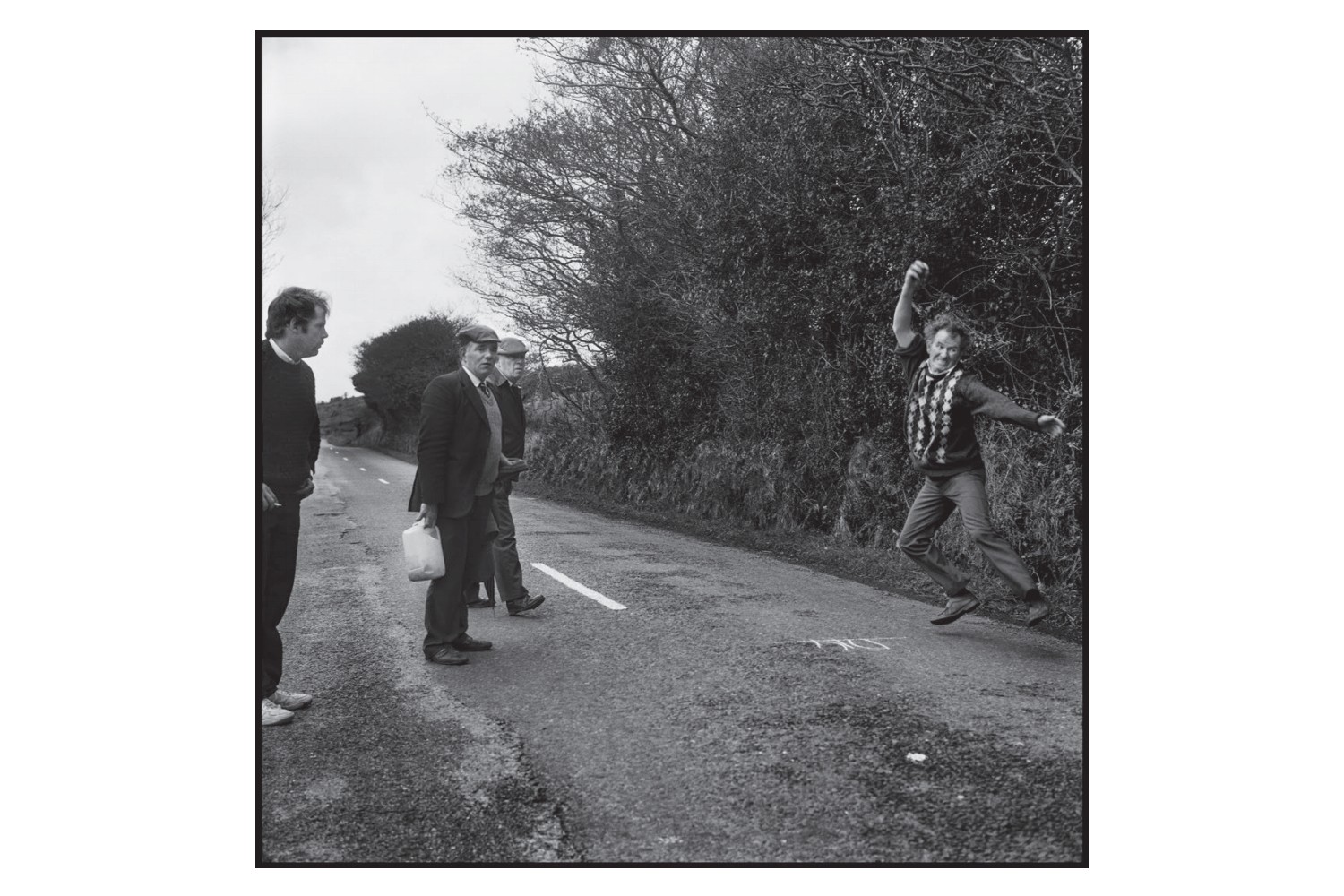

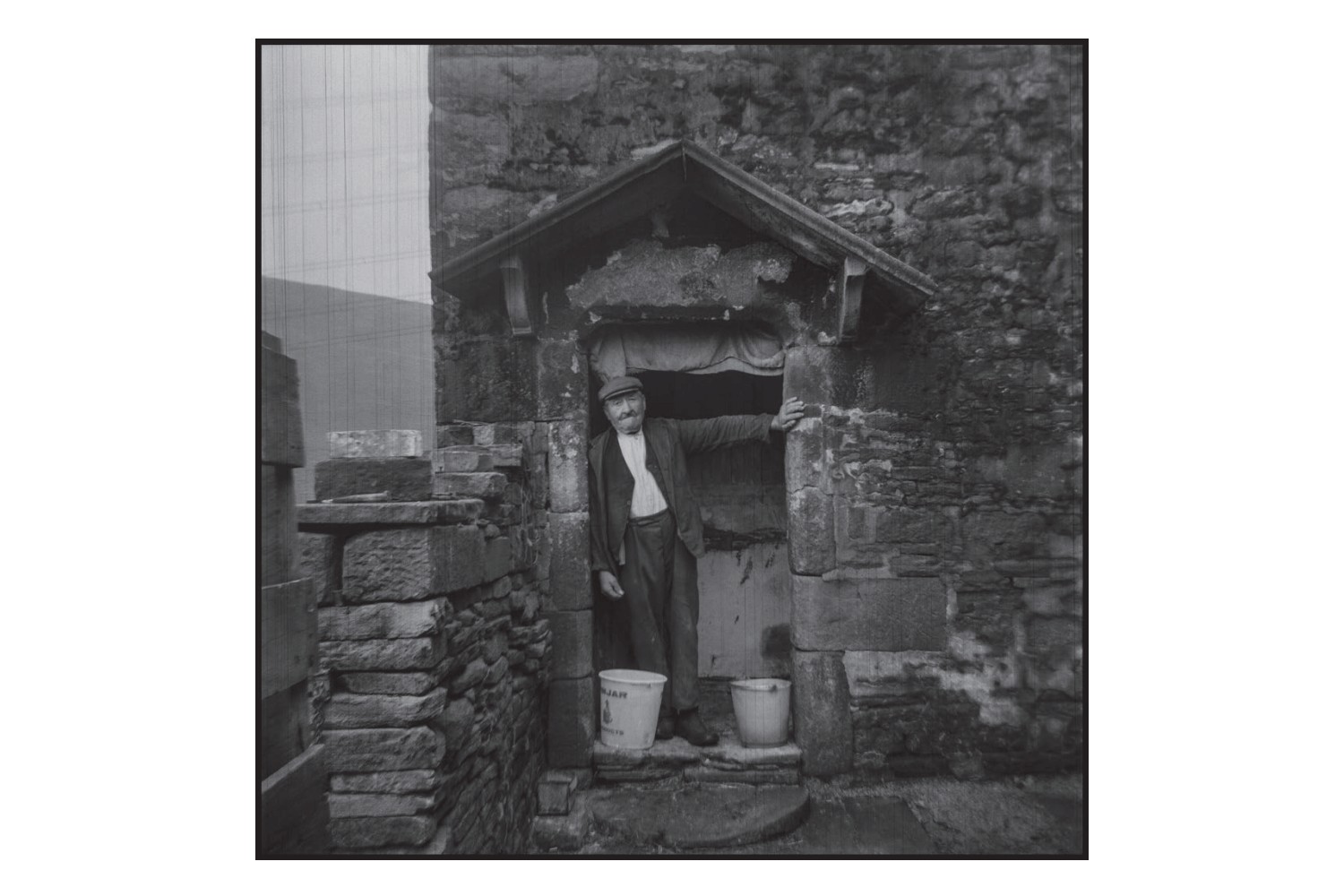

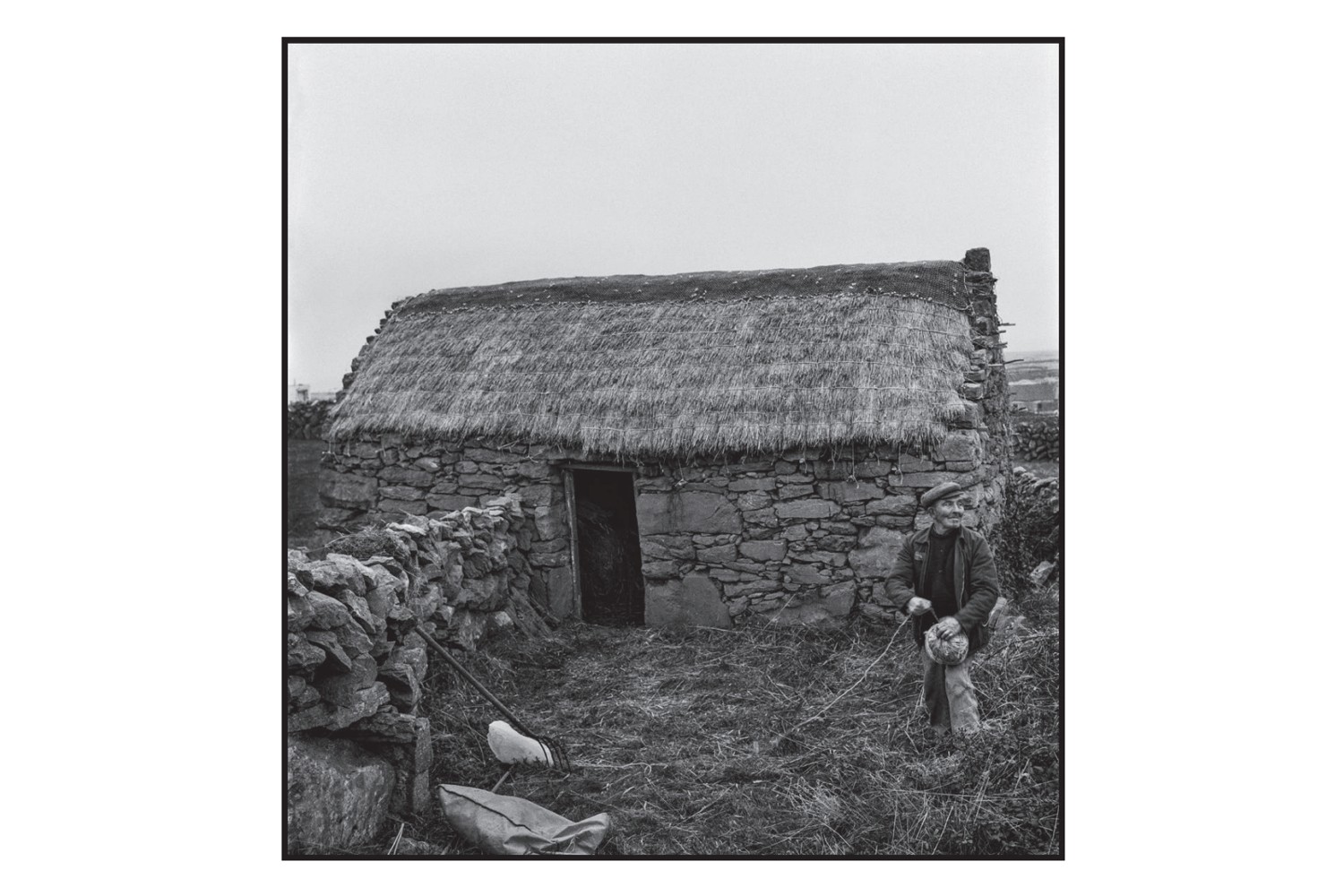

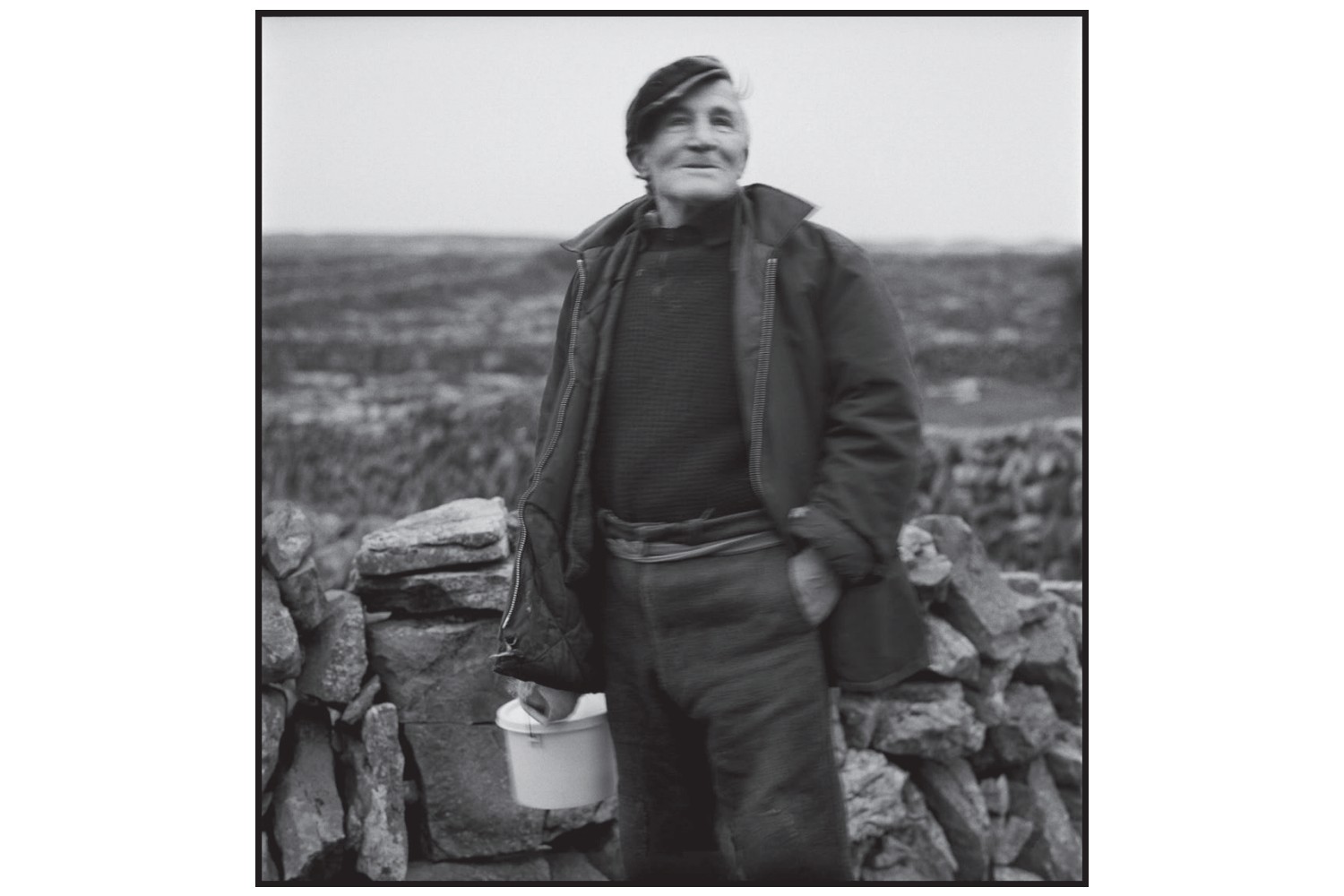

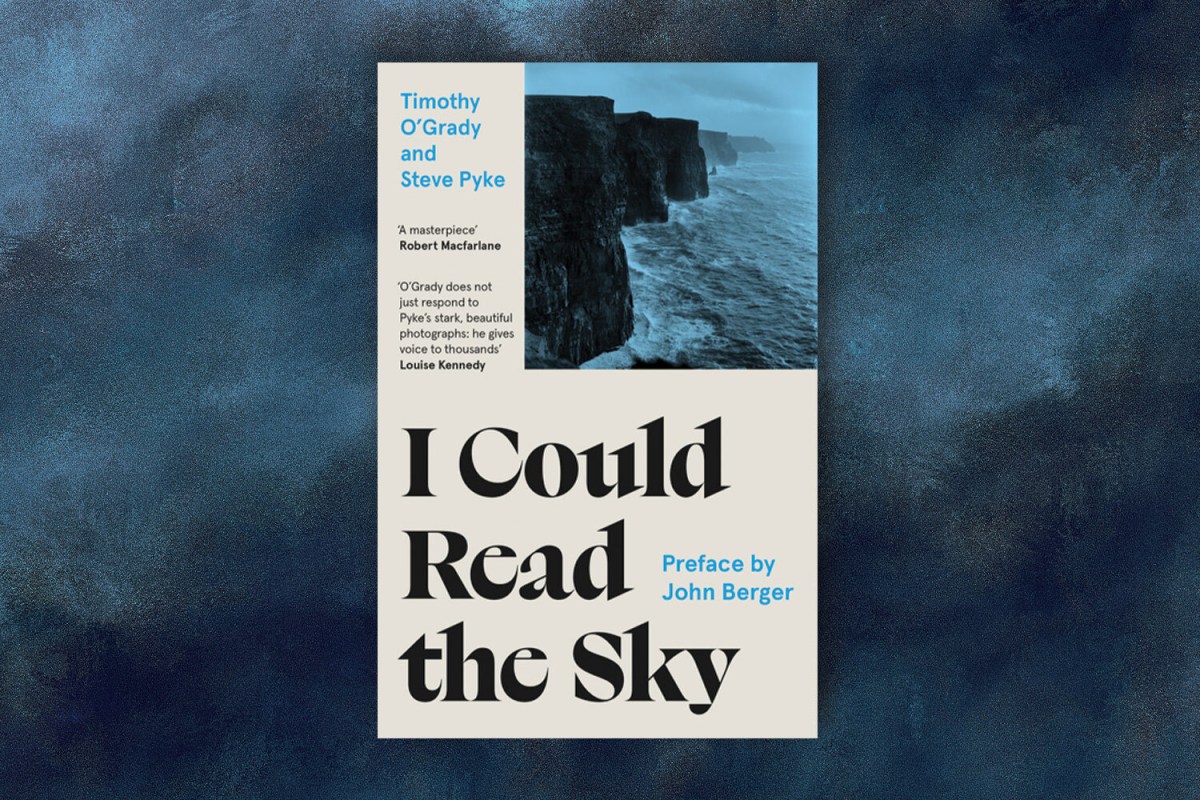

Can the right combination of words and pictures evoke the raw stuff of memory? In 1997, a collaboration between writer Timothy O’Grady and photographer Steve Pyke offered one answer to that question. I Could Read the Sky is a journey into the past, structured as the reminiscences of an aging Irishman whose life took him far from home. A film adaptation starring Stephen Rea and Maria Doyle Kennedy soon followed.

Now, I Could Read the Sky has been reissued in a new edition that finds the ideal balance between its creators’ respective disciplines. The story of how that came about is a winding route indeed — one that’s almost as memorable as the words and pictures that evoke a bygone era of Irish history.

“The route to this book was very different from any other book I’ve ever done,” O’Grady tells InsideHook. “It started, really, with a publisher, rather than something that was internal to me. What happened was that [Pyke] was photographing different people, among them was Iris Murdoch.”

It was through Murdoch — the Booker Prize-winning author of The Sea, The Sea, among others — that Pyke’s photography gained a foothold in the publishing world. “Iris Murdoch brought them to this woman Carmen Callil who was a big force in English publishing,” O’Grady explains. “I had written a novel for this publisher and they had the idea that they could get me to write something [here]. They asked me to write something to go along with the photographs, so then they contacted me about that.”

Critically acclaimed writers weren’t the only subject of Pyke’s work. As O’Grady recalls, Pyke had also spent a lot of time in Ireland photographing its residents and landscape. It was these photos that would spark the genesis of their collaboration.

O’Grady started his work with more than a little skepticism. “I started looking at a lot of different collaborations that photographers and writers had made, most of which seemed to me unnecessary,” he says. “There was no reason for there to be words and pictures together. One was subservient to the other, they were sort of decorated essays or glorified captions.”

As he went further into the project, he encountered work that changed his mind. “One person who had really deeply thought about it and done very interesting things with it was John Berger,” O’Grady says. “From the 1950s on, he collaborated with a Swiss photographer called Jean Mohr.” That proved to O’Grady that prose and photography could complement one another in a mutually beneficial way. He went on to cite James Baldwin’s collaboration with Richard Avedon and Let Us Now Praise Famous Men as other works that informed I Could Read the Sky.

Still, it’s Berger — who contributed this book’s introduction — who looms especially large for O’Grady and Pyke’s collaboration. “I saw a book that John Berger had done about photography in which there was a sequence of about 80 pages of photographs,” O’Grady says. “There were no words, but it was clearly the remembering of a woman from the Alps who had become a domestic servant in Paris and came back. It was just done with pictures and that’s what made me think it could be fiction.”

Finding the medium was one thing; finding the story was another. “It took me about two years to figure out that this could be a novel. I thought it was going to be something about memory. I thought, Ireland is laden with memory: political memory, familial memory, memory of the dead, memory of a pre-conquest kind of Eden — all kinds of memories but one of the main sources of memory in Ireland would be immigration,” O’Grady explains. “There’s four or five million on the island and about 200 million all over the world.”

In writing this book, O’Grady drew on his own experience of leaving home to live abroad — in this case, moving to London from the United States. “My experience of Irish immigrant life in London was the pubs where music was played. You could see the network that existed all around London that Irish people knew English people didn’t know about and that Irish people didn’t know the rest of the network of London,” he recalls. “They were almost autonomous systems of living and communication, and for the Irish a lot of it was united by these pubs.”

From there, O’Grady found his narrator, via what he dubbed “a rather peculiar thing.”

“I was living in London. I came back late one night to where I was living in winter, and I lay down. And this voice not my own came into my head speaking very clearly: ‘This room is dark, as dark as it ever gets — the hour before dawn in winter. Something stirs then, a little wind.’ And I couldn’t get rid of it,” he says.

Late-night moments of inspiration are frequent for writers, though O’Grady acknowledged that they don’t always hold up. “If these ideas come to you and you get up out of bed on a cold night and write them down, often in the morning you might wish you hadn’t because they’re not worth having been written,” he says. “But in this case, it was the beginning of the book. It was the syntax and the feeling of the character and the rhythm of his thinking, it was the atmosphere of the book, and then it didn’t take long to write.”

Finding the right balance of words and images remained challenging. “We made a couple of trips to Ireland together, where I was telling him what I was writing and what might be the type of thing to photograph,” O’Grady recalls. “[Pyke] already had a lot of photographs. And we were then inclined to do what we didn’t want to do, which was to illustrate. And we couldn’t get away from that.”

As it turned out, the solution came from another artist, filmmaker Nichola Bruce. “Then [Pyke’s] partner at the time, who was a filmmaker — she actually made the film of I Could Read the Sky — she found a way to arrange the photographs without any reference to the words, just as I wrote the story of those pieces. But they kind of touched together,” he says. “We refined this so that they coincide sometimes. And that’s basically how we made it.”

Ireland’s Original 5-Star Lodge Is a Bucket List Item

Do yourself a favor and get to Sheen Falls Lodge

Finding the right balance of words and images wasn’t something confined to the book itself; it also related to the production of I Could Read the Sky. As O’Grady revealed, a question that lingered was of the best format for the book: a larger one which might prioritize the images, or a smaller one which might prioritize the text. In the end, the book’s initial publisher opted for both.

“The Harvill Press extraordinarily published a large edition and a smaller edition. But [Pyke] designed the large edition with the publisher and I designed the smaller version with the publisher so we never really did one together,” O’Grady explains. “It stayed in print as a paperback on increasingly cheaper paper and worse and worse production reproduction quality. And finally it was just in print on demand. I was trying to get them to up the quality of it and they wouldn’t do it.”

Eventually, this led O’Grady to contact Unbound about printing a new edition. This also led to the two collaborators working together on a new edition of the book — one that would do justice to both disciplines. “It was all done in one day in the Unbound offices in London. Steve was coming through and he only had one day. So we started in the morning, we finished at night, and we did it finally together with their help,” O’Grady says.

“It’s about two and a half times as thick as the previously existing paperback, because of the paper. I feel the photographs are much more present now than the earlier edition,” he adds. “There’s a dynamism that it didn’t have before in the telling of the story. You really do feel that the story and the words are moving you through this experience — at least I do, that’s how I feel about it.”

It’s a powerful journey through space, time and memory — the result of a collaboration that led to O’Grady and Pyke working together on other projects and O’Grady finding new ways to blend artistic disciplines. I Could Read the Sky is a moving, evocative work — and it’s now out in the world in an edition that does well by both of its creators.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C750)