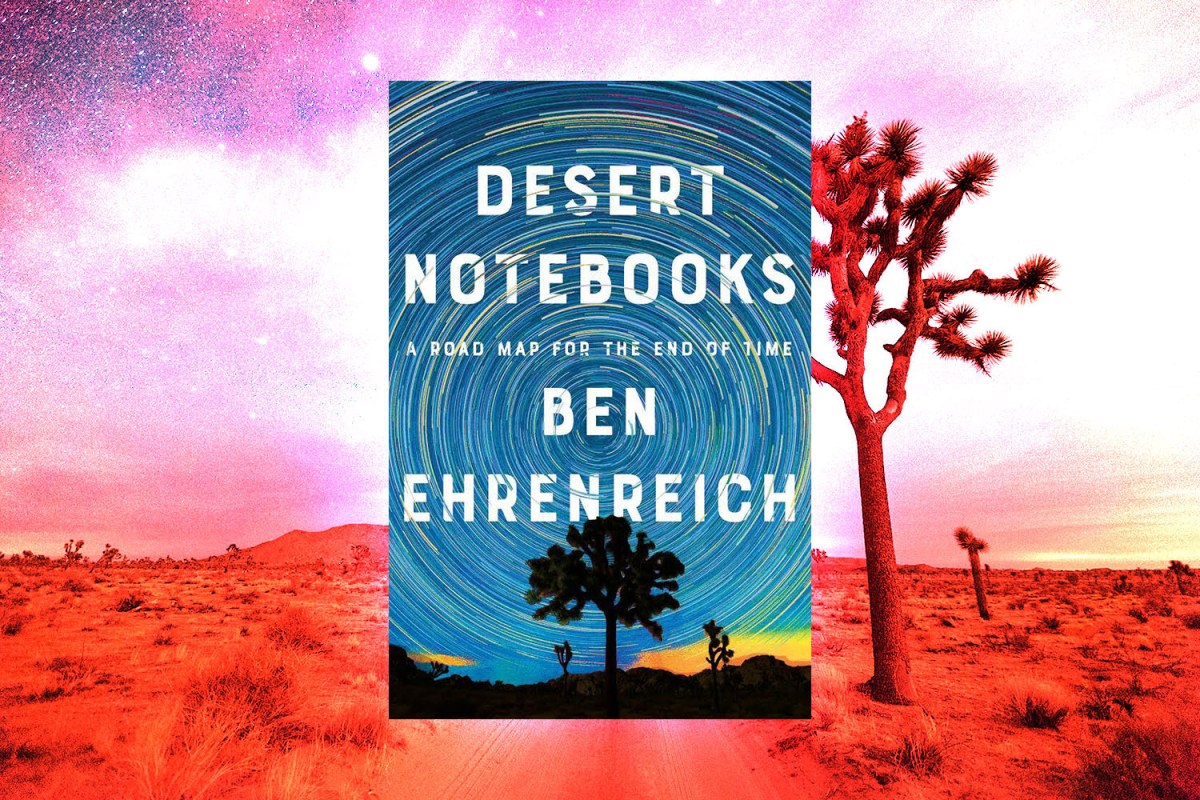

One afternoon in November 2017, in Joshua Tree, California, Ben Ehrenreich was out hiking with friends when he saw a couple of owls. This doesn’t seem like an auspicious starting point for a razor-sharp work of environmental writing. But owls are creatures steeped in centuries of mythology, the Mojave desert is a deceptively complex ecosystem that’s been brutalized by climate change and Ehrenreich was tenacious enough to follow those threads and see where they took him. The result, Desert Notebooks: A Road Map for the End of Time, is a remarkable work of cultural history and environmental polemic, at once a stirring portrait of the desert in its purest form and a lament for what’s been done to it in the name of progress.

Ehrenreich, speaking via Skype from England (though his current home base is Barcelona), tells InsideHook he wasn’t sure where his daily diary entries inspired by that owl-spotting would lead, but was confident they’d eventually cohere. “I felt fairly sure that there was something there, even if I couldn’t articulate it in the beginning,” he says. “For most of the time that I was writing, if I tried to explain to anybody what I was doing, I sounded like a lunatic. ‘Yeah, I’m writing about [Jewish mythological figure] Lilith and I’m writing about the [Mayan sacred text] Popul Vuh and I’m writing about [philosophers] Jacob Boehme and Hegel and Walter Benjamin.’ Nonetheless, I knew that I would be able to shape it into something.”

Part of the reason Desert Notebooks does hold together is Ehrenreich’s graceful, thoughtful writing about its two key settings, Joshua Tree and Las Vegas (where he did a brief writing fellowship). Though only about 200 miles apart, they represent different worlds. In Joshua Tree, Ehrenreich has an epiphany-like moment observing the night sky amid the emptiness, considering the smallness of his existence. Vegas is crowded by contrast, but Ehrenreich is less concerned with the glittery malls and casinos than the fact that they’re built on the past violations of nuclear tests and the disenfranchisement of native peoples. Yet he sees a stubborn ecosystem in both. “The desert practically shouts that at you, all day and all night, that it, and life in all its resiliency and multiplicity and magic, pulsing force, will go on,” he writes. “Whatever we do or don’t do, whether we’re still here or not.”

“I came to understand [the desert] not as a place of death and barrenness and waste and absence, but a place that was actually teeming with life,” he says. “If you pay attention, everything is alive, and it’s in many ways more subtle in how it manifests its vitality. If you spend time there you’re attuned to its delicateness, its fragility, but also its incredible stubbornness.”

But Ehrenreich only wants to romanticize the desert so much, because his main point is that humanity has run roughshod over it. (In his book, he symbolizes that destructive instinct via the “Rhino,” his nickname for President Trump, a man who “only ever wrecks things.”) Ehrenreich engages with mythologies from the Mayans, Egyptians and other ancient civilizations to better explain how Western culture created its own myths to justify its conquests of “savages.” Indeed, Western society has persuaded itself that the industrial progress that led to man-made climate change was humanity’s sole trajectory, a mindset at once arrogant and blinkered. (“We could make the skies darken at noon, and brighten the night, and shift the very winds and the currents of the seas,” he writes. “Who else but man could melt a glacier? Who else but man could burn it all?”)

That’s part of the reason why Ehrenreich doesn’t see Desert Notebooks as part of the prominent environmental literature on the Southwest exemplified by writers like Edward Abbey and Charles Bowden. Those writers may have possessed a deep-seated love for the region, but were often undermined by a machismo and racism that blinkered them to crucial elements of its history.

“The only works that I have come across that reflected the desert that I came to know were works by native people,” he says. “I talk a lot in the book about various stories from the Mojave, the Chemehuevi and those actually make a lot more sense to me. They reflect the desert that I know both in its complexity and abundance of life, but also their humor. Rocks and animals all coexist and have consciousness and speak and have ridiculous adventures. I think in the way most white people have written about the desert, there remains this incredible divide between the sort of observing consciousness and the material and animal world of the desert.”

Desert Notebooks tracks Ehrenreich’s journals through the spring of 2018, a time that featured Trump’s saber-rattling over North Korean nuclear tests along with worrisome news about melting glaciers and wildfires. Compared to 2020, it was a gentler era. The current moment feels like a proof of the book’s concept to Ehrenreich: The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that nature isn’t particularly interested in our concerns about economic progress. It’s literally killing our myth-making.

“It’s hard to understand 140,000 deaths as a teachable moment,” he says [Editor’s note: The U.S. COVID-19 death count reached 150,000 after this story was filed.] “But I think one of the twisted virtues of this virus is that it has, with incredible pinpoint accuracy in every single society that it has hit — which is now every society on the globe — revealed the weak points, the inequalities, the failures of those societies, and taken advantage of them. So all the ways that we failed to take care of our own, all the ways that we consider a certain people expendable, all the ways in which we mistreat one another — this virus has jumped on all of that. In the past we could pretend, or some of us could pretend, that those inequalities and those cruelties and those enormous structural failings didn’t exist, because some people were doing OK. This virus makes it very clear that a lot of us were not OK.”

But the message of Desert Notebooks is meant to resonate beyond any election or pandemic. Throughout the book, Ehrenreich worries over what he’s doing, questioning the value of the written word in times of crisis. (The primacy of writing over pictographs and other ancient methods of communication is one of the myths he tangles with in the book.) But though he’s uncertain about how much a book can motivate people, he says he was determined to find a way for humanity to get out of its “cul de sac.”

“I wanted to launch as concrete a critique as I possibly could of the ways of thinking about our relationship to each other and to the planet,” he says. “I have some faith as a writer — and this may be a false faith — that by exposing myths as myths and by exposing lies as lies, and by showing how certain views of our own history are in fact self-serving and completely incorrect, that perhaps we can set ourselves up on a different relationship to our own history and to each other.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C750)