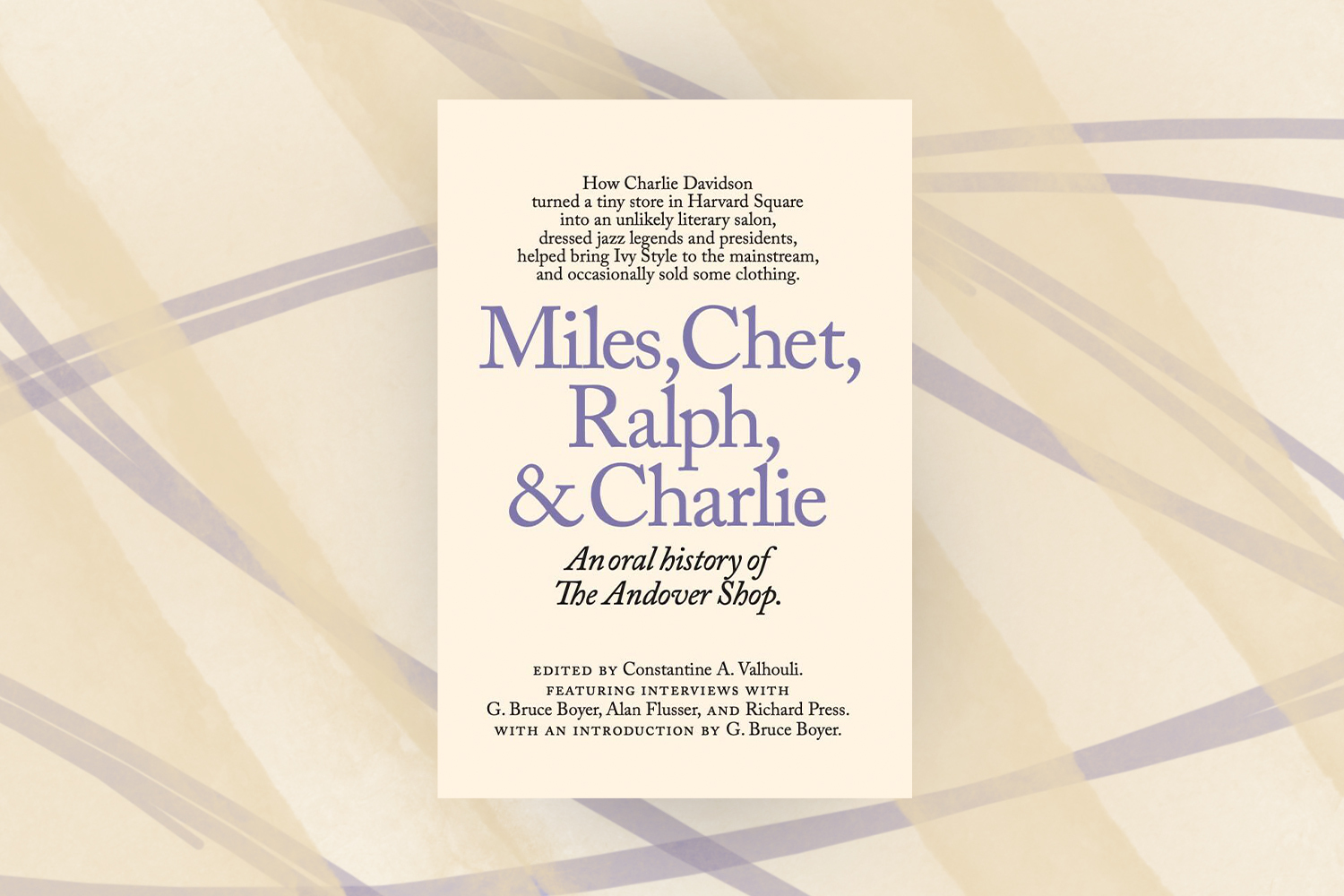

History doesn’t occur in a vacuum; why should the history of menswear be any exception? Learning about style can lead to countless points of overlap with other fields. That’s one of the reasons that editor Constantine Valhouli’s new book Miles, Chet, Ralph & Charlie: An oral history of The Andover Shop is so fascinating. If you have an interest in menswear, you’ll find plenty to savor in its pages, both in terms of how it chronicles the evolution of style and how it demonstrates how some of the 20th century’s biggest names found their own signature looks.

Miles, Chet, Ralph & Charlie goes far beyond that, however; even readers who might not know the ins and outs of Ivy style will find plenty to savor in the descriptions of the jazz legends, politicians and public intellectuals in Andover Shop founder Charlie Davidson’s circle. What made The Andover Shop such a destination for leading figures in their chosen fields? That’s a question that runs throughout the book.

InsideHook caught up with Valhouli to learn more about his own history with Davidson, the process of putting the book together and what Davidson’s legacy is today.

InsideHook: At what point did you begin thinking about putting together some sort of a book about The Andover Shop? Were you ever concerned that you wouldn’t have enough material for a book?

Constantine Valhouli: I knew Charlie [Davidson] for almost four decades, and was privileged to call him a friend, but he was a deeply private man and I did not know many of the stories which formed the core of this book until his memorial service. He led a fascinating and meaningful life, and part of it was that he didn’t see it (or himself) as particularly extraordinary.

Writing the book was simultaneously worrisome and such fun. Worrisome because it covers a long life and there was a sense that many readers needed to be introduced to key cultural figures that have since been forgotten. But such fun because oral history is basically about conversations with fascinating people. I was having such a blast with the book that I hoped that the eventual readers would feel the same way, too.

In your introduction, you mention your decision to structure this as an oral history. Did you always have that in mind, or did that come up later in the process?

The credit goes to Nelson W. Aldrich, Jr. for the notion of structuring it as an oral history. Nelson had done an oral history of his Paris Review colleague George Plimpton (George, Being George, which is an absolutely marvelous book). And George and Jean Stein had done several oral histories ranging from Truman Capote to Edie Sedgwick. Nelson and I were working together on the Finley book at the time, and I was having trouble structuring these wonderful interviews into a cohesive narrative. After looking over my notes, he saw that the book was full of wonderful storytellers, and that the best thing I could do was to get out of their way and foreground these distinctive voices. His advice was spot-on, as it always was.

How much of the interviews did you do directly versus looking into archival materials?

One of the joys of the book was the opportunity to speak in such depth with people like Bruce Boyer, Richard Press and Alan Flusser, whom I admire deeply. Individually, they have written some of the seminal books on American style, and this was one of the few opportunities to bring them together in discussion. And debate. The oral history format lends itself to the fact that not only are there differing recollections, but very different points of view.

Each of them gave me a reading list and suggested other interviews, so the book emerged from a fascinating mix of personal interviews and archival research. The latter became critical for the key figures in the book who had died years ago — Ralph Ellison, Albert Murray and so many of the jazz musicians — to give them a chance to tell their stories in their own words.

How did you go about organizing the book? I was especially impressed with chapter titles like “In which Charlie casually mentions that they all hated each other.”

So, to this day, I’m not sure if Miles, Chet, Ralph & Charlie is actually my first or second book. I began the Finley book first, but finished Miles, Chet, Ralph & Charlie while Finley was still underway. I had no idea what I was doing, and feel that still holds true. I’m not sure if the book was ever “organized” in the usual sense of the word, so much as cobbled together with a whole lot of coffee and duct tape … those chapter titles were originally just my notes to myself, and then someone else said, “Hey, that’s actually not bad,” and I sort of coughed and pretended that I had done that on purpose.

One of the aspects of the book that really resonated with me was the description of The Andover Shop as a kind of salon, where thinkers and enthusiasts could come together. What about that space contributed to it?

I think Charlie was the motive force behind this. People were drawn to him, in part because he made them shine. But there were two other factors: locations right off the campus of Harvard and of Phillips Academy, so by default it drew a particular crowd of academics and intellectuals. I also think that the stores were small enough that it sort of forced customers into discussion. One asks the person across the table to hand him one of those sweaters, and suddenly you’re in conversation with Cornel West or Skip Gates. Who are telling you that green isn’t your color.

You mentioned a few times that there were offshoot shops from The Andover Shop; was there a similar mood there?

Could I reframe the question? The progenitor of the traditional American style was Brooks Brothers, and J. Press emerged at the turn of the last century to refine that style. Many of the defining menswear companies of the 20th century were founded by J. Press alumni — The Andover Shop, Chipp, Sills, Gant, and I’m sure I’m forgetting a few. Stylistically, they ran the gamut from understated elegance to whimsical playfulness.

You Can’t Tell the History of Menswear Without the History of Pockets

Hannah Carlson on getting to the bottom — literally and figuratively — of “Pockets”When looking up some of the names of the people featured in here, I noticed that Mor Sené went on to start his own shop. Was he the only alumnus of The Andover Shop to go into business for himself?

I think he might have been. He’s actually starting a school for tailoring and fashion in Senegal, and there will be a room devoted to the memory of Charlie Davidson there.

Was there anyone who you encountered in assembling the book whose sartorial tastes surprised you?

Everyone in the book, actually. I was delighted at the stories of how Charlie Davidson helped so many iconic figures find their signature styles, and how he didn’t repeat a trick. People didn’t leave the store looking like Charlie, but rather more like themselves.

And if anything, Charlie understood the power of clothing to signal aspects of identity and belonging and aspiration. His advice was guided by that understanding.

Early on in the book, a kind of “admissions test” is mentioned for prospective clients of The Andover Shop. What did that entail?

Building on the above, Charlie knew that his style advice held some power, and he was cautious about who he wanted to confer his gifts upon. I recognize that this sounds melodramatic, but it’s true. It wasn’t about money, as he turned down some industrialists who were recommended to the shop. It wasn’t about prestige, either. I think he didn’t want people whom he didn’t enjoy darkening his doorstep. There’s a memorable scene in which Charlie and Larry forcibly evict a Styleforum member from the Shop.

You’ve also been working on a book about Harvard professor John H. Finley, Jr. Are there other pieces of under-discussed Harvard history that you’re planning to cover in future projects?

At one point, Nelson Aldrich pointed out that the two books cover stories that happened literally two blocks from each other. John Finley’s Eliot House was just down the street from the Andover Shop. And then I realized that in my ever-growing list of things to write, a good number occurred within the surrounding blocks. I should probably branch out a bit, maybe even get really daring and write about places on the other side of the Charles River. But there’s something about Cambridge that particularly resonates with me, how there are tangible connections to so many threads of American history.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.