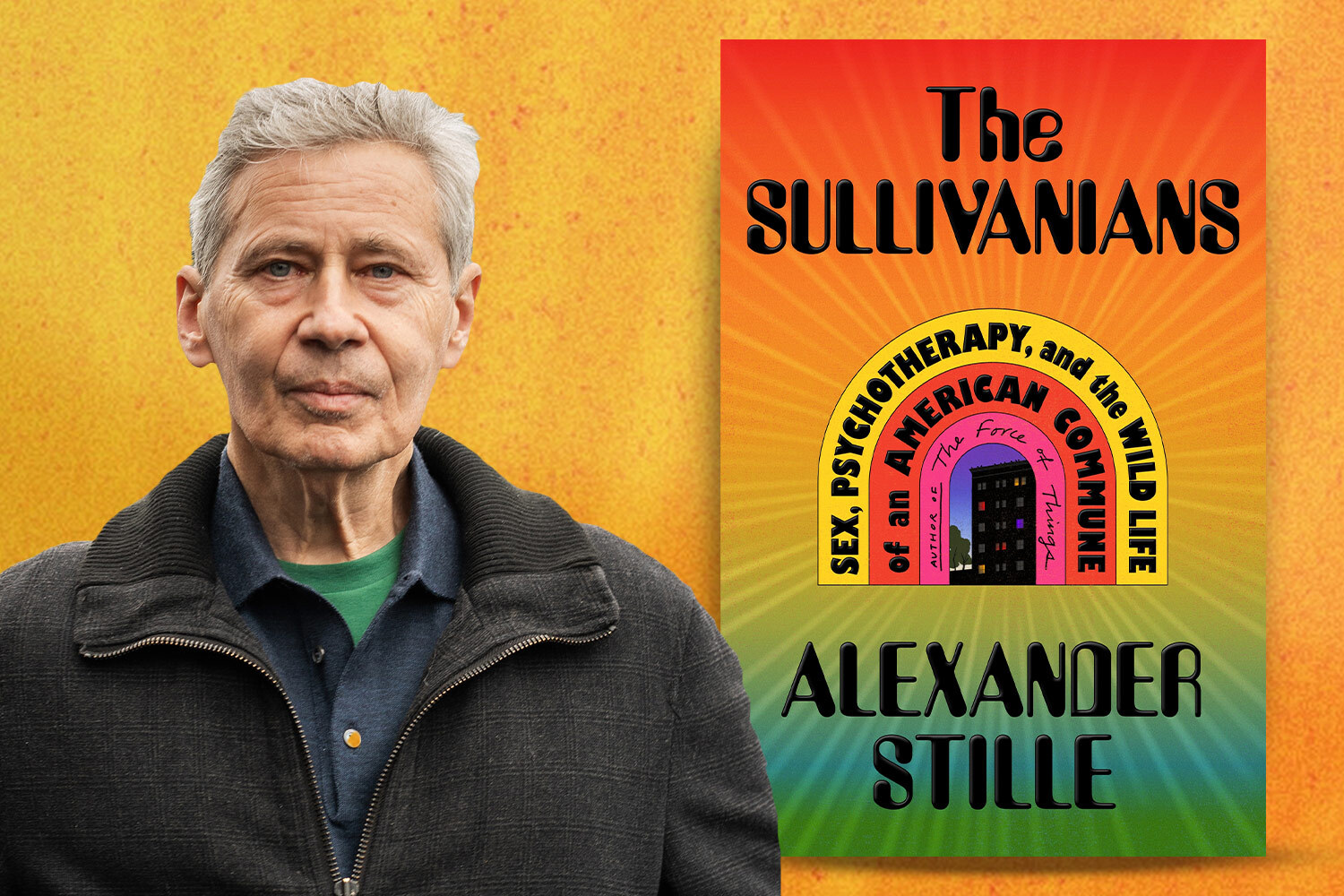

At what point does an organization, however well-intentioned it might be, become a cult? That question hangs over Alexander Stille’s new book The Sullivanians: Sex, Psychotherapy, and the Wild Life of an American Commune. Stille’s book focuses on an experiment in communal living that began in New York City and gradually went from therapeutic into something closer to a nightmare.

Stille’s book covers a lot, from the notable creative figures whose lives overlapped with the movement (including art critic Clement Greenberg and novelist Richard Price) to the Sullivanians’ ill-fated foray into politically-minded theater. The full history of the Sullivan Institute incorporates chilling abuses of power, all against the backdrop of a changing New York City.

Stille spoke with InsideHook about the process of researching the book, the ethical questions raised by the Sullivan Institute’s history and the ways that it forever changed those who took part in it.

*This interview has been edited for length and context.

InsideHook: In the past, you’ve written a lot about Italian history, about the history of fascism. What attracted you to writing about a very different kind of authoritarian society,but one a little closer to home?

Alexander Stille: It certainly wasn’t part of any programmatic strategy on my part. I’m a journalist and journalists are generalists. I mean, I have developed a specialization in Italy, but have always been open to interesting stories wherever they come from. And I stumbled on this one rather by accident. A couple of friends who happened to be parents in my son’s school were telling me about two older people that they knew, whom they’d gotten to know quite well and had a really unusual interesting past in this group.

I lived on the Upper West Side of of Manhattan for quite a long time and was fascinated by the idea that I’d been living in this neighborhood for decades and knew nothing of what was essentially a secret utopian society that had existed for 30 years in our midst that functioned according to its own laws and its own precepts and was at variance with mainstream society. That was really interesting.

I had been interested in counterculture in general. I didn’t end up writing that much about it, but I had been very interested in the protest movements in Italy in the 1970s, the Red Brigades and other left-wing protest movements. So it wasn’t completely out of my bailiwick but I’d be lying if I said that it was part of some sort of grand strategy or or building an oeuvre of some kind. It was really just following my curiosity and pursuing a story that just got more and more interesting the deeper I got into it.

It wasn’t just the people who were in the group, but it was also the children that were conceived and raised in this community, their whole story and their drama. I didn’t really know that sexual abuse was necessarily gonna be a part of the story, but then it just kept coming out in the course of interviews. So the story got deeper and more complicated the further I got into it.

I didn’t think I was going to be writing a book when I started out. I actually thought I was going to do a podcast. But the deeper I got into it, I just interviewed more and more people and gathered more and more material. And my longtime book editor said, “There’s no way you can do this in even an eight part podcast, you have to do a book.”

In The Sullivanians, you wrote about your interactions with some of the members of the group and your interviews with them, and the process of tracking them down. It also seems like several members had ended up writing books about their time in the group, or in the case of the one writer who had been Richard Price’s teacher, he had written some fiction that was inspired by that. What was the first layer of your research for this book like?

Well, they, the one book that really existed when I started working on this was a very, very valuable one that had begun as a PhD dissertation by a woman who had been raised in a group first as the child of a patient, then as a patient from the age of eight to 16, and then returned as an as a young adult in the 70s. And so she wrote a sociology PhD dissertation which is a fairly academic book, but a very, very useful one that helped to really get me going. I then sought her out. She still lives in the New York area. I interviewed her. I then discovered that her husband had been a therapist in the group and was willing to talk to me and that and he ended up being a central character in my book because it was incredibly interesting to get the perspective of people who’d been on both sides of of the therapeutic relationship — who had been patients initially then became, were trained as therapists in the methods of the group and had really, really insightful interesting things about both sides of that relationship.

Her book contained some names. I then discovered that someone I knew actually had been in the group, and I contacted her and she was kind enough to talk to me — and then someone came out of the woodwork who I didn’t even know about who said, “I hear you’re working on this. I have my diaries from that period, I have membership lists, I have a lot of other information from that time.” So I went and tracked her down and it just expanded from there. There were just a lot of different things that were milestones in the whole reporting process.

How long did the process of researching and writing this end up taking you?

About four years, four and a half years. A good chunk of that was also writing and rewriting. So maybe the research took two years and two years for the writing and rewriting.

This was all happening in New York at a very particular time in the second half of the 20th century. Do you think that something like this group could have arisen in New York at any other time? Or do you think it really had to have been at that time, with inexpensive real estate widely available?

Certainly now, it would be really hard to do something like this. As you say, one of the preconditions to this group was the availability of a lot of inexpensive real estate on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. So New York between like 1950 and 1975 or so lost a million inhabitants. Manhattan lost half a million, and the great majority of those were white. And so you had neighborhoods like the Upper West Side that were just depopulated. Everybody moved to the suburbs.

These grand pre-war apartment buildings that were originally meant for upper middle class families with, you know, three or four bedrooms, a maid’s room, a formal dining room, so on and so forth were beginning to deteriorate and rent for next to nothing to students and people like the people in this community. The rents were, by today’s standards, almost comically low, and so you put six people together in a group apartment and you were paying next to nothing in rent and giving a third of your salary to your therapist and working two jobs and doing this and that, and you had a life.

It’s possible that in earlier decades when cheap rent was also possible, something like this could have happened, but this also was the confluence of a series of other cultural things that happened. So psychoanalysis was at the peak of its power and influence in our society in the 40s and 50s. Everybody wanted to be analyzed as part of their maturation process. New York was the center of psychoanalytic thinking and fervor in this country. And then you know there was, in the case of this particular group, the 50s was the high water point for the hegemony of the Ozzie and Harriet-type family, the traditional family with the male breadwinner, the mother at home, three kids who were perfectly behaved and so forth.

There was a building up of resentment and rebellion against that model. And then you get birth control coming in and suddenly there’s this idea that the old way of doing things isn’t necessary any longer. We’re now free to rewrite the rules and to make society according to our own needs and desires and not according to what tradition has told us we should want. This becomes a very exciting, liberatory program for people in this group.

In recent years, it seems like the number of people in non-monogamous relationships has — if not risen, then gotten higher-profile. And, and to some extent, you also can read about more ways of experimenting with communal living arrangements for adults. What was it like researching and writing this and finding these moments that rhymed with the time in which you were writing it?

As one of my main characters says, we asked all the right questions and got all the wrong answers. So the questions that they were asking — there’s a lot of loneliness and alienation in our society. Capitalism produces extremely unequal results, people search for a more authentic life, they need freedom from the particular strictures they grew up with. All those things are things that people feel intensely. The problem in this case was that therapists felt empowered to lay down the law and to interfere with patients’ lives in a way that I think most of us would find to be way over the top.

Those problems of wanting to go beyond the particular little box that society has assigned to us are genuine problems that people are searching for solutions for. And so — polyamory, the returning popularity of socialism, Jacobin, all those sorts of things are, I think, part of that mix. And so I think it’s then interesting to then look back at an earlier generation that tried to address those things.

Of course, there have been other attempts like this in American history. The Oneida community in upstate New York was very similar. They came up with the idea of complex marriage and they were egalitarian, they were abolitionist, they were quite radical in certain ways and believed in female empowerment, but it also became overly rigid and eventually fell apart because people rebelled against some of the rules. So this sort of thing is a recurring theme in American history.

How did your understanding of the group change as you began doing research and talking to more people about it?

In general, as I got to know the people I was interviewing well, and they opened up to me, stories were just jaw-dropping. I would be talking to them and say, “You did what? And what happened?” One of the things that I gradually became aware of was how powerful the nature of groups can be, to get people to do things that they wouldn’t normally do.

I was interviewing one of my interview subjects for maybe the fourth or fifth time, and she then starts telling me that she had participated in kidnapping a child on behalf of a group member who wanted to take the child away from its father. Not because she wanted to raise the child herself, but in order to take this seven-year-old child back to boarding school where he was miserable because that happened to fit the precepts of this group.

It’s interesting, I’ve been hearing a lot in the last several days since the book came out from people who were in the group who are now reading the book and reacting. And in many cases, there were even people that I spoke to who told me their piece of the story, but they said, “Wow, I never knew so much of this stuff went on. I knew about my story, but I didn’t realize that these things were so pervasive.”

One of the things that I began to put together as I talked to so many people was that within this group everyone was isolated in their own little silo and so if something bad happened to you, your therapist screamed at you, you were forced to sleep with somebody you didn’t want to sleep with, one of the leaders hit you, you didn’t tell anyone because that was only going to invite trouble. You were then becoming a dissonant sort of person who’s complaining about the group. So everybody kept their problems to themselves. As somebody who’s talked to dozens of people within the group, you get a mosaic of the whole picture — and they themselves are quite surprised. “Wow, I didn’t know all this stuff was going on. And yet it also fits what was happening to me. I always thought it was just me, my story.”

So I think that is something that not only did I learn in the course of the reporting, but that I’m still beginning to take stock of as I’m hearing from people who live this experience.

One of the things that really resonated with me about the book was the way you dealt with the question of, was this a cult or not? You brought up the fact that like a lot of the abuses of power that happened within the hierarchy are also things that have happened within various religious groups as well, wherever there is that concentration of power and someone is able to abuse that power.

One reason why I don’t completely shy away from the use of the word cult, but I don’t like to use it too often — because I think it gets in the way of understanding things — is that many strict forms of religion operate according to similar principles in that, if you have the most strict forms of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Mormonism, there is a very strong sort of group identity, a strong sense of us against them.

“Us” is pure and good and “them” is impure and bad. There’s a high, the group demands a lot of you and gives you a lot. There’s a community that will sustain you but then there’s a very, very high cost of exit. If you are a ultra-Orthodox Jew, they say shiva for you which is the prayer for the dead, if you leave that community, you are dead to them. I’ve spoken to ex-Mormons that came from quite strict Mormon families. And if you left the community, you lost a lot of friends and relatives who would no longer deal with you. And that’s, of course, a devastating thing for someone to lose their family relations or community.

So those are strategies that religious groups and also political groups use to maintain internal solidarity and group spirit and to negotiate with the outside world. This group, in that sense, was not so different.

I thought it was very important to understand these people as complex human beings, they were not zombies, they were not losers, they were not, adult teenagers at the bus station who were picked up and taken off to an ashram somewhere. They were smart, high-performing professionals who got into this for initially pretty good reasons, and then were kept in by the power of the group. And so I think it’s important to see that as an understandable human phenomenon. I think the word “cult” tends to evoke something very other, and these people were not other.

One of the major incidents in the book is a Village Voice exposé in the 1980s. Besides a piece about a decade earlier in New York magazine, there really had been very little coverage of the group and what had been going on there. Why do you think that is? Is it just that they went under the radar for that long?

Part of it is they were very, very resistant to attention. So for example, when David Black, who wrote the article in 1975 for New York, approached them about doing something, editors at New York said, “We’ve always wanted to do something on this group, we can never get started, we just can’t penetrate it.” And so what David Black did is he signed up for therapy. He actually went into therapy with a Sullivanian analyst — and even that piece really didn’t get terribly far because people wouldn’t talk to him much. So

As he later told me, it was Richard Elman who really got him to do that piece and so he had Richard Elman and his experience and a little bit of that but he really didn’t get deep into it. Apparently as soon as that piece came out the therapist who treated him, even though she had no idea what he was going to do, was kicked out of the group and that was it.

There was a guy who wanted to do either a long research paper or a dissertation about the group who was a group member. That guy was kicked right out and they claimed that he was a CIA agent. So there a lot of the group had quite well-developed defense mechanisms in order to keep things opaque. They couldn’t do that in 1986 because this one group member who had been denied access to her daughter kidnapped her own child off the streets of Manhattan. Her husband, the father of this child, filed a lawsuit to regain custody of the child. So that then broke the story into the public realm.

There were court filings and this woman was told by her lawyer, talk to the press. They actually set up the Village Voice thing because they said, they can’t deal with the publicity, and it will help to bring the group down. So her willingness to cooperate — and by then there was a group of several people who had left group who were willing to talk either on or off the record to the Voice — that made it possible to write about the group in some depth at that point. But those conditions hadn’t existed before.

You described a lot of incredibly compelling things in this book — some horrific to read about, and others that were more surreal, including buying a fleet of school buses and sending a group of people to occupy a theater on the Lower East Side. Was there any one thing that, as you researched it, just struck you as stranger than fiction?

There are things that happened in the group that were shocking in a deeply upsetting way. For me one of the most poignant and terrible moments in the book where you have these kids who have been sent away to boarding school at very very young ages against their will. They could be six, seven, eight, in one case even three years old, and one of the boys who was sent away, his father is no longer in the group and therefore happy to see him and spend time with him. So he’s on vacation from this terrible boarding school in Arizona where several of the kids in the group are sent. And he gets to see his father for a week.

He’s desperate for parental attention. And then he knows that his mother is not going to see him because they’re against parent-child relationships and he’s going to be sent back to boarding school. And so the father says, “Well, why don’t you just stay with me for another week until school comes back in?”

They go out for a walk to get an ice cream in Central Park and they realize that people are following them. And suddenly there’s a crowd of group members who are following them and they get panicky and they go back to the father’s apartment and people are banging on the door and they call the police.

There’s this whole scene and the police ask the boy, “Who do you want to be with, your mom or your dad?” And he says, “My dad.” But then the father knows he doesn’t legally have custody at that point. And then the mother calls and the mother says to the child, “You can stay with your father, but you’ll never see me again.”

The boy turns to his father hoping he will say, “That’s okay, you can stay here, you’re my son.” And the father doesn’t have the wherewithal to say yes. He says, “Gee, I don’t know, that’s a lot to ask. I don’t want to take responsibility that you’re never gonna see your mom again.” And the boy goes back to the mother and she doesn’t even take them back to her apartment. She has his plane ticket and they get in a plane to LaGuardia and he goes back to an empty boarding school that’s closed where there are other kids in the group staying.

That’s one of the most heartbreaking moments that I’ve personally experienced even as a reporter. And there were many, many moments like that where you just thought, wow, I can’t believe that a parent could be so cruel to a child that way.

That happened. And that boy who now is a man, a person with a good life, he said, “That happened to me. My mother did that to me. And I’m still processing that fact.”

A New Memoir Recounts Growing Up in a Cult and Learning to Love the Outdoors

Michelle Dowd’s book, “Forager: Field Notes For Surviving a Family Cult,” is out nowOne of the really fascinating things that you brought up at the end of the book is that a lot of people who left the group or were raised in the group seemed to have gone to work in the areas of medicine or mental health or whatever else. It felt almost reassuring that they were perhaps trying to prevent something like this from ever happening again.

A lot of these are very smart, thoughtful people. I expect they’re probably pretty good therapists. I interviewed a couple of psychotherapists who treated people who were in the group as they got out of it.

One point that they made, which is I think a really interesting one, is that so these people left the group and suddenly they snapped back into who they were before. They reestablished relationships with their families, if those people were still alive. They went back to doing their chosen profession instead of what their therapist told them they should be doing.

On the one hand, that’s reassuring, — “I am who I am.” But then you say, “Who was I for the 15 years I was in this group? What is the nature of my identity if it’s so malleable?”

I had one of my interview subjects say to me, “I was not myself for 20 years.” I’m not equipped to evaluate whether something like that is an absolute truth, but that’s certainly the way she felt. And I don’t know quite what you do with that.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.