What does the word “Targa” mean to you?

If you ask Leslie Kendall, chief historian at the Petersen Automotive Museum, he’d guess most drivers today associate it with a specific type of vehicle: “People look at a car with a designed-in roll bar and they’ll say, ‘Oh, that must be the Targa version.’”

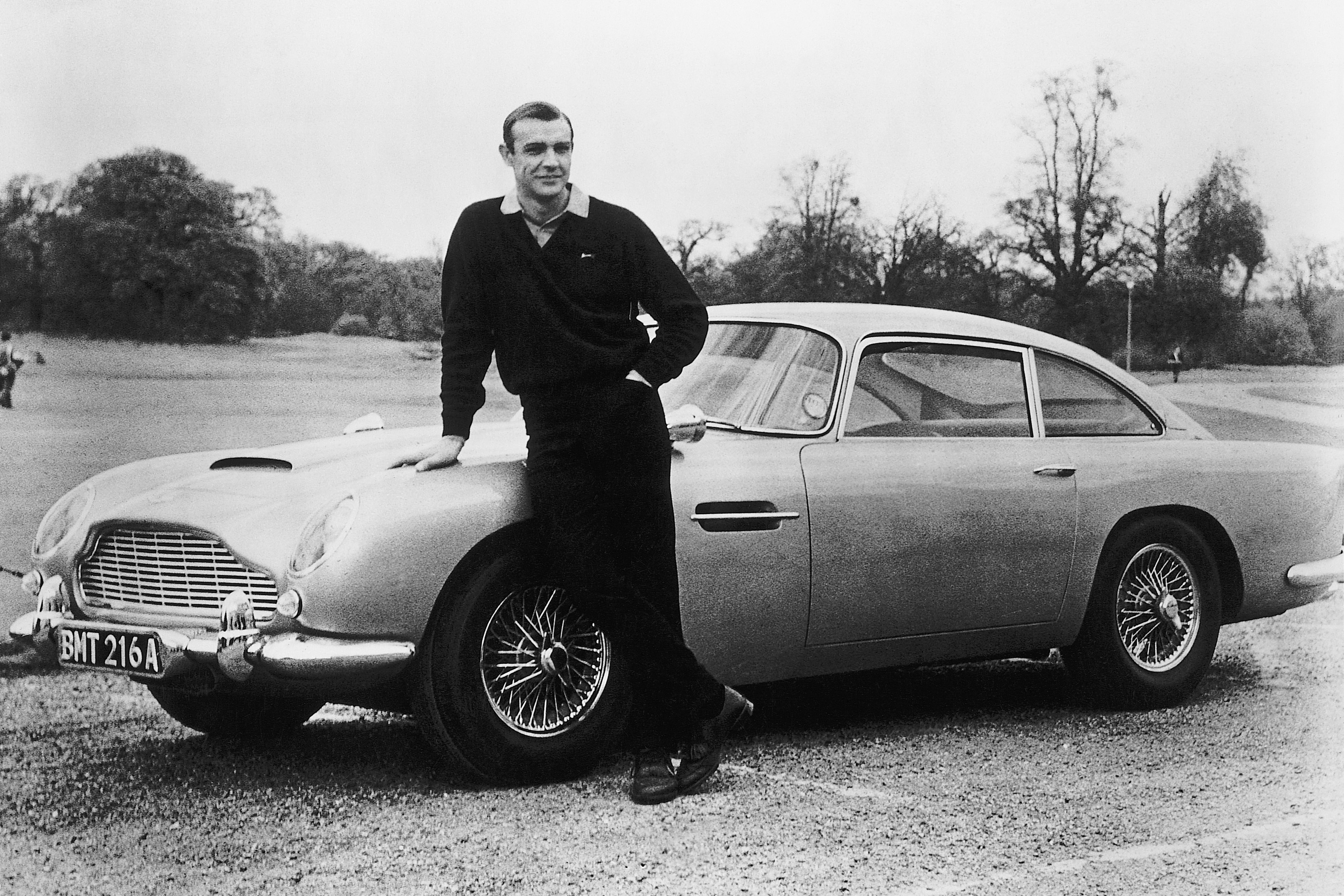

You can thank Porsche for that modern definition. The German automaker unveiled the Targa body style in 1965 at the International Motor Show in its home country — an open-top car with a removable roof panel, soft plastic rear window and fixed roll bar behind the driver — a response to the U.S. potentially implementing, as Kendall says, “very, very strict” roll-over laws. In the end, those laws never panned out, but the Targa remains a staple of the Porsche buying experience today.

The history behind the Targa name, however, goes back long before the automotive safety requirements of the ‘60s. In some respects, its story is the antithesis of them: a tale of a madcap race up and down the mountains of Sicily, where the question wasn’t who would win, but, as Kendall puts it, “Who’s going to survive?”

That race was the Targa Florio, one of the most important events in motorsports history. But before it achieved that fame and was then repurposed by Porsche, it started quaintly enough, with a race that was won by, quite literally, one horsepower.

Vincenzo Florio: The Gentleman Racer

The Targa Florio is one of the oldest automobile races, taking its name from founder Vincenzo Florio, who started it in 1906 on the picturesque, mountainous Italian island of Sicily. It was a groundbreaking event at the time (remember, Henry Ford didn’t start producing the Model T until 1908), but the history of the race begins even a few years earlier, when Florio bought one of his first motor vehicles, brought it to his home island and decided to try his hand at racing.

The problem? No one else had gas-powered vehicles at the time, so he compromised. “The very first [race], I believe, was between a bicycle, a horse and a car,” explains Kendall, “and the horse won.” The car was actually a De Dion tricycle, which was more akin to a three-wheeled motorcycle than a modern-day car. But despite that demoralizing start, Florio became more determined than ever to preach the gospel of the automobile.

“He wanted to promote the automobile and his passion for it,” Paul Baxa, associate professor and chair of the history department at Ave Maria University, tells InsideHook. Florio was able to take up that expensive hobby because he was part of one of the wealthiest Sicilian families, who had their hands in everything from wine to shipbuilding. Florio would eventually help build the historic Monza race track in Italy, as well as found and take part in a number of automotive clubs, but his legacy remains in this namesake race.

The Most Grueling and Most Romantic Race

For most Americans, auto racing comes down to one factor: speed. We associate the sport with national events like NASCAR and unofficial races like the Cannonball Run, and with movies like the Fast & Furious franchise. If the U.S. prizes simplistic pedal-to-the-metal racing, the Targa Florio, and Sicilians by extension, championed a more romantic style known for its tenacious drivers, fanatical audience and medieval track as much as the cars that drove on it.

David Biggins should know. He produced the 2015 documentary A Sicilian Dream about the Targa Florio, but only after he bought a 1913 Nazzaro and raced it around the Targa in 2006, the centenary of the first race. The car was built by Felice Nazzaro, who won the race in 1907 and 1913, the first time in a Fiat and the second in an automobile of his own making. It was the “only time anyone has won in his own built car,” Biggins says.

The first races in the early 1900s, he notes, “were held on mule tracks as there were no proper roads.” Those mule tracks were lined with peasants while the grandstand at the starting line was populated by European high society. Even after those scrappy initial years, when the races were mostly won by pioneering automotive companies whose names may not even be recognizable to historians (Fiat and Peugeot being notable exceptions), the Sicilian track remained an appealing challenge — the Everest of racing, if you will.

Professor Baxa, who holds a Ph.D. in history, specializes in Italian fascism and has an acute interest in the role motorsport played within that society, including the Targa Florio. When asked to set the scene of the race, he described it like this:

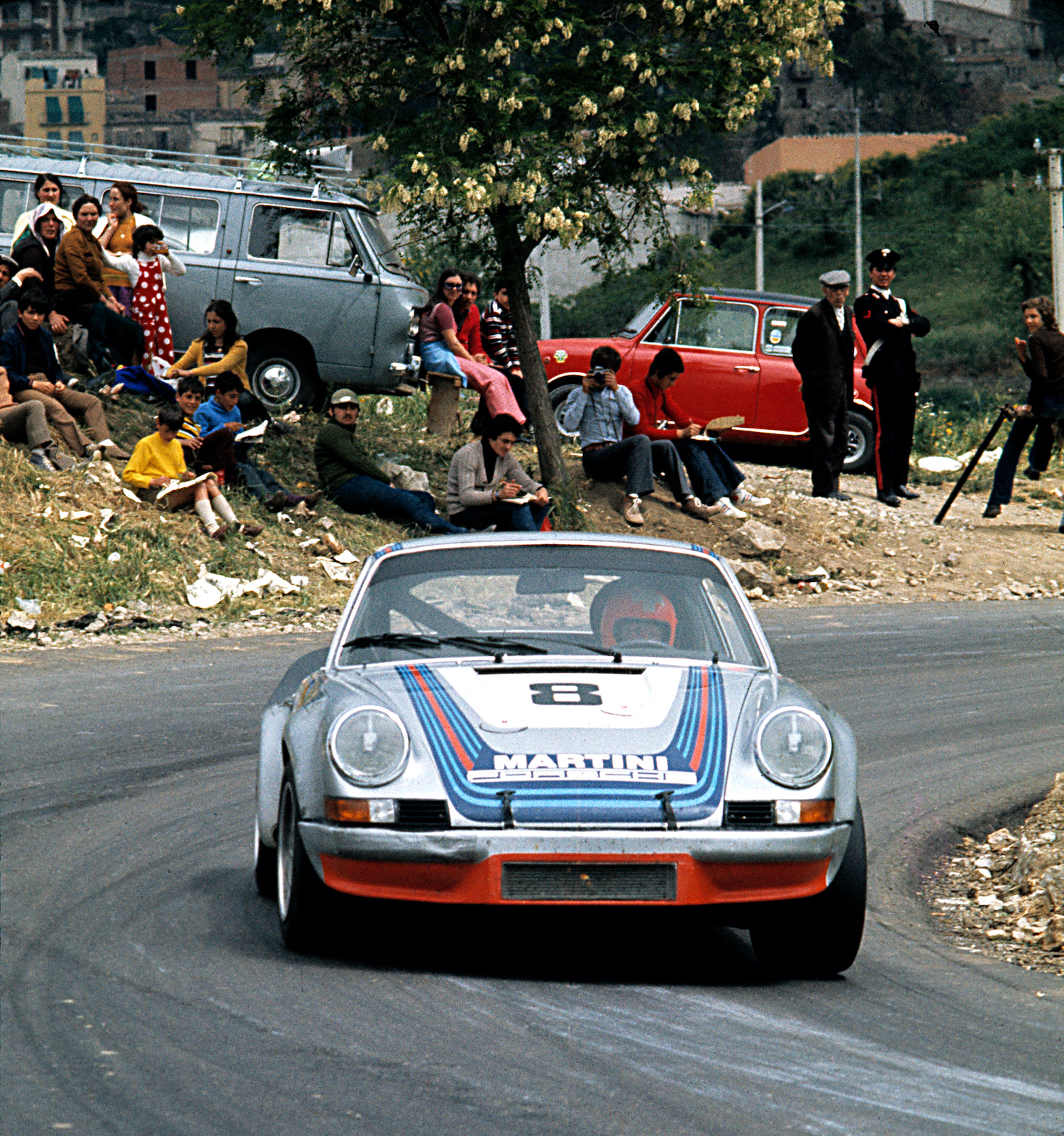

“The prototypes and GT cars, which are kind of the fastest sports cars, they’re going through these narrow streets in these Sicilian villages. And these villages look the same as they did centuries ago. The roads are very primitive, and it goes up into the mountains and then back down the mountains to the seafront. But the road is torturous; its twists and turns, a lot of hairpins, very grueling. Every now and then they’ll go through one of these villages which, again, there are no signs of modernity … There are these old houses along the main streets and they just power through under balconies with people hanging over and cheering and waving. You’ll see crowds sitting right along the circuit through these hairpin bends, these people sitting on low stone walls.”

“It was the toughest and most grueling of all the road races for both cars and drivers,” adds Biggins.

And it attracted some of the biggest names of the time, including Enzo Ferrari who, as Baxa says, talked about the dangers of the radical changes in climate in the mountains, the precipitous drops on the hundreds of turns, and even the bandits that roamed the countryside. But the founder of Ferrari raced it anyway.

Due to the Targa’s long history, Baxa was reluctant to define a specific heyday, instead pointing to the many significant eras, from the groundbreaking beginning to the Bugatti dominance of the 1920s to the inclusion of the race in the FIA’s World Sportscar Championship from 1955 to 1973, when the wins were for the most part a back-and-forth contest between Porsche and Ferrari. During those years, in the middle of which the automaker unveiled its Targa model, Porsche vehicles finished first in 11 of 19 races.

“The Targa Florio Must Never Die”

After the 1973 race, the World Sportscar Championship dropped the Targa Florio because, as Baxa says, “it was just too dangerous.” The cars were getting too fast, the 45-mile course (shortened from the original distance of about 92 miles) was too long and remote to erect barriers, and there were fatalities among both drivers and spectators.

Simply reading The New York Times account of that final FIA race is harrowing: one driver was hospitalized after his Alfa Romeo ran off the road, another in a Chevron B23 seriously injured three spectators who were sitting on a wall when he crashed into it, and a BMW driver injured four more. That didn’t stop the race from continuing in a national capacity for four more years, but in 1977 a crash killed two fans, and the days of the Targa Florio as a prestigious endurance race were over.

But while the outside world has retreated from the Targa, and Vincenzo Florio’s passion for the automobile has outgrown his homeland, Sicilians still hold onto their history. As Baxa notes, the original pits and grandstand can still be found in the town of Cerda (the area where the starting line was located is known as “Floriopoli”). And as Biggins can personally attest, the race has continued in various forms, from a vintage race to a modern rally.

“Towards the end of Vincenzo Florio’s life, he was impoverished and bankrupt due mainly to … his brother who squandered the Florio fortune,” says Biggins. Nonetheless, the auto impresario said, “The Targa Florio must never die.”

Over 100 years later, Sicilians are upholding Vincenzo’s final wish, and you can too — by remembering the Porsche Targa is so much more than a body style.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.