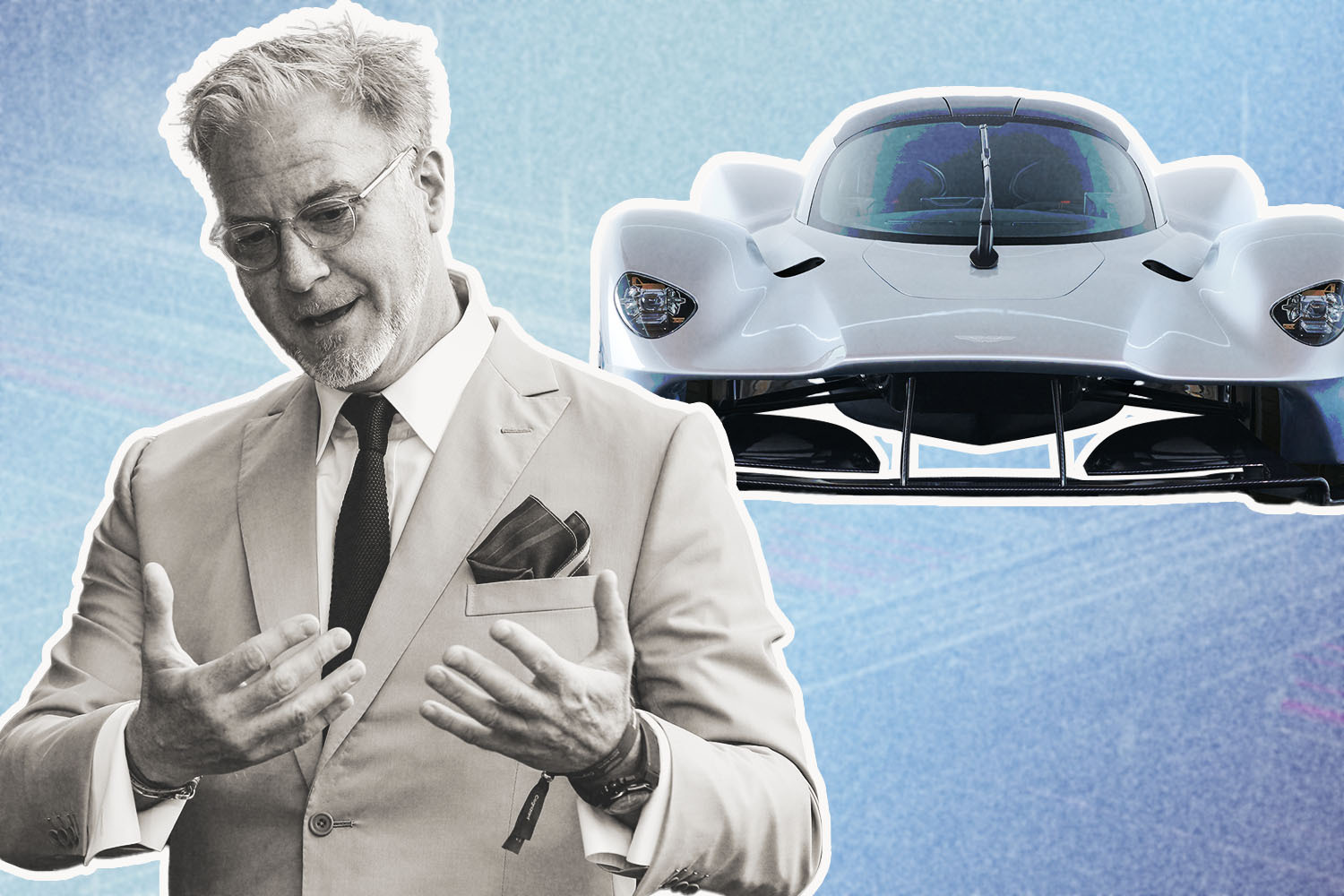

“I have shed a little tear every now and then,” laughs Marek Reichman. The design director of Aston Martin for the last 17 years is bemoaning the passing of the rumbly and growly V12. As if the impending overhaul of the James Bond franchise — with which the British carmaker has been intimately associated since 1964 — wasn’t worrisome enough, the new Vantage will be the last Aston Martin to have such a huge engine under its hood.

“But there’s actually more freedom of form in designing electric engined cars,” Reichman adds, saying what is, in some petrolhead quarters, the unsayable. “If you think about a V12, or a V8, it’s a pretty big and hard lump with a certain mass and volume and positioning, and then compare that with a smaller, lighter, infinitely configurable battery pack. You can imagine the scope to do things differently. The industry hasn’t been brave enough yet in pursuing a new form language. If you look at a Tesla, it looks like a normal saloon. I don’t think Elon was prepared to give drivers a new way of interacting with a car, a new form of propulsion and a new style too. But that will come.”

Reichman may work at one of the most esteemed carmakers in the world, but he’s all about change. He says change, for him, is the very definition of design. On the one hand, he jokes, absolutely nothing has changed at Aston Martin during his time there, where he is currently the chief creative officer and executive vice president. His task has been the same: to make “beautifully proportioned cars, and I like to think that if an alien landed from Mars and saw a DB5 without knowing what it was, they would think the same.” On the other hand, everything has changed: Reichman has had to embrace new technology and materials and extend Aston’s design language to a hypercar and an SUV alike.

“I think they’re all recognizable as an Aston Martin, such that you don’t even need the grille anymore,” he adds. “You can look at an Apple product and you just know it’s Apple. And I hope that’s the same for Aston Martin products.”

Indeed, “products” is the apt word, because although Aston Martin will, says Reichman, always be about cars, it has dabbled in applying its signature to a motorbike in conjunction with Brough Superior, founder Lionel Martin’s choice of runabout, and, much less aerodynamic than Aston Martin cars typically, an apartment block in Miami and even a whisky bottle for Bowmore.

“I got more thumbs up on LinkedIn for that bottle than I did for the Valkyrie [hypercar],” says Reichman. “What does that mean? That there are more alcoholics on LinkedIn? I don’t know. And of course it looks like nothing like an Aston Martin. It’s a whisky bottle. But we’re able to say it looks like the Aston Martin of whisky bottles. I think that shows we have strength in the brand.”

But then Reichman has always thought of himself not as a car specialist but as a more broad-minded industrial designer. Sure, it still has wheels, but little known is the fact that Reichman co-developed the new generation of London’s iconic Routemaster bus.

“I don’t want to discredit anyone in car design, because styling is incredibly important. Styling is receiving a platform, not really understanding how to change it, and putting a beautiful form over it,” explains Reichman. “But an industrial designer — and I’m an industrial designer who happens to love cars — works from the blank sheet of paper with the engineer, working out how to make the visual language integral to its manufacture.”

“The people who designed the Spitfire weren’t tasked with making it look good,” he adds. “They were told to make an aeroplane that will outperform this other aeroplane. And they used their knowledge of aerodynamics, materials science, aluminum bending, and so on, and ended up with a beautiful object. In the same way, I’m tasked with finding the best solutions for a product, and at the end of the day for the company too. You have to be able to build and sell these objects and make a profit on them.”

That Reichman’s work is shaped by business-minded problem-solving perhaps stems from his background. Born in 1966 in Sheffield, still England’s heavy industry heartland for steel-making while Reichman was growing up, he says his enthusiasm for cars came from his “car nut” brother, though his broader fascination for how things work, the “thinginess” of stuff, came from his father, a blacksmith.

“Back then you’d see the sparks come over the factory walls and feel the vibrations, before the factory became the world’s biggest shopping mall,” Reichman recalls. “Watching him develop these incredible pieces of metalwork fascinated me. He made me curious about how things are made. His philosophy was always ‘if it’s broke, try to fix it.’ We had the TV spread over three chairs for a while. He’d made it work again but couldn’t put it back together. We couldn’t go near the TV in case we got electrocuted.”

Reichman studied design at the Royal College of Art in London. Before he got to Aston Martin he had already worked with Rover Cars, BMW Designworks in California, and Ford, having a hand in designing the Lincoln MKX, the Range Rover Mk III and the Rolls-Royce Phantom. He left Ford for Aston Martin and in the first year he’d designed its first-ever four-door car and saw the DBS put James Bond back in an Aston, too.

Now he faces arguably the most interesting challenges of his career, especially given that, ostensibly, he’s long been focused on designing noisy, thrilling sports cars. Now he faces electrification and the rise of the SUV.

“Is the SUV the future of cars? It’s a very interesting question. Gen Zs and the Millennials already see SUVs as just the standard definition of ‘car.’ If I ask design students to draw a car, they draw an SUV. That tells you how the language of cars has changed,” he explains (it’s a trend he knows intimately well as the lead behind Aston Martin’s massively successful DBX) .

“Will it spell the death of sports cars? I don’t think so. It’s like horses. They were once used for pulling, for lifting, for work. Now they’re for the leisure of riding or eventing or racing. The same will be the case for sports cars. They’ll offer driving for pleasure. Of course, they will have to meet emissions regulations. But they’re already sustainable in a way. If you think that 96% of Aston Martin cars ever built still exist, they’re not actually things you dispose of. That said, if at the moment the highest priced cars have two doors, I think in the future SUVs will be the collectible cars. And, of course, the industrial designer in me sees that in the more distant future we’ll all move around in electrified pods, or some such, because driving patterns now make no sense at all.”

That might send more shudders through the petrolhead community: the man who has sculpted Aston Martin for almost two decades saying that the future may be automated and regulated. The lure of the open road it isn’t. But Reichman isn’t scared.

“The challenge is to make beauty and simplicity and dynamic form apply to whatever the market demands, and that changes,” he says. “The bus was one of the most exciting projects I’ve ever worked on. The technology in that thing was incredible. And it was through that that I learned what makes an icon.”

Maybe that’s why he’s confident that, by the time James Bond is back on the big screen, the reboot will allow for some kind of Aston Martin to be there with him too. “Wherever we are and whatever we’re doing, I think Bond will seek us out,” says Reichman. “It’s a partnership. It would be a brave director that left out an Aston Martin.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.