Something subtle and insidious has happened over the past decade or so of driving: the cabin of your car, truck or SUV has been invaded by an occupying force of dings, chimes, klaxons and flashing lights, each one vying for your attention in the middle of your morning commute.

The unified goal of this sensory bombardment? To convince you that the litany of automated safety equipment installed in your vehicle is keeping you more secure while you engage in perhaps the most dangerous activity any of us partakes in on a regular basis.

There’s no way around it: driving is risky. Operating a complex machine on a vast, high-speed network of roads filled to the brim with similar apparatus that’s also crisscrossed by pedestrians, wildlife and cyclists is going to put people and property in jeopardy on a regular basis. And yet the act is often painted as the most mundane of tasks, a slog to be endured on the way to work, school or the mall, and it’s usually only when inclement weather enters the picture that most of us stop to consider the actual skills that are needed to make it home in one piece.

If you’ve spent any time inside the cockpit of a modern automobile, you’ve no doubt experienced the symphony of light and sound intended to remind you of the perils lurking in every blind spot. But what if all of this prescient protective tech is actually having the opposite effect? What if constant digital hand-holding out on the road is teaching an entire generation of drivers to disconnect behind the wheel?

And what if all the data showed us that not only is this true, but that it is getting worse by the day?

Passive to Active

Beginning in the 1960s, automotive safety focused on protecting drivers from the effects of a crash by way of seat belts, crumple zones and eventually airbags, each of which mitigated the nasty physics inherent in a collision. By the end of the 1980s, anti-lock brakes and traction control systems began to make a convincing argument that intervening before an accident could take place was an even smarter play than preparing for impact.

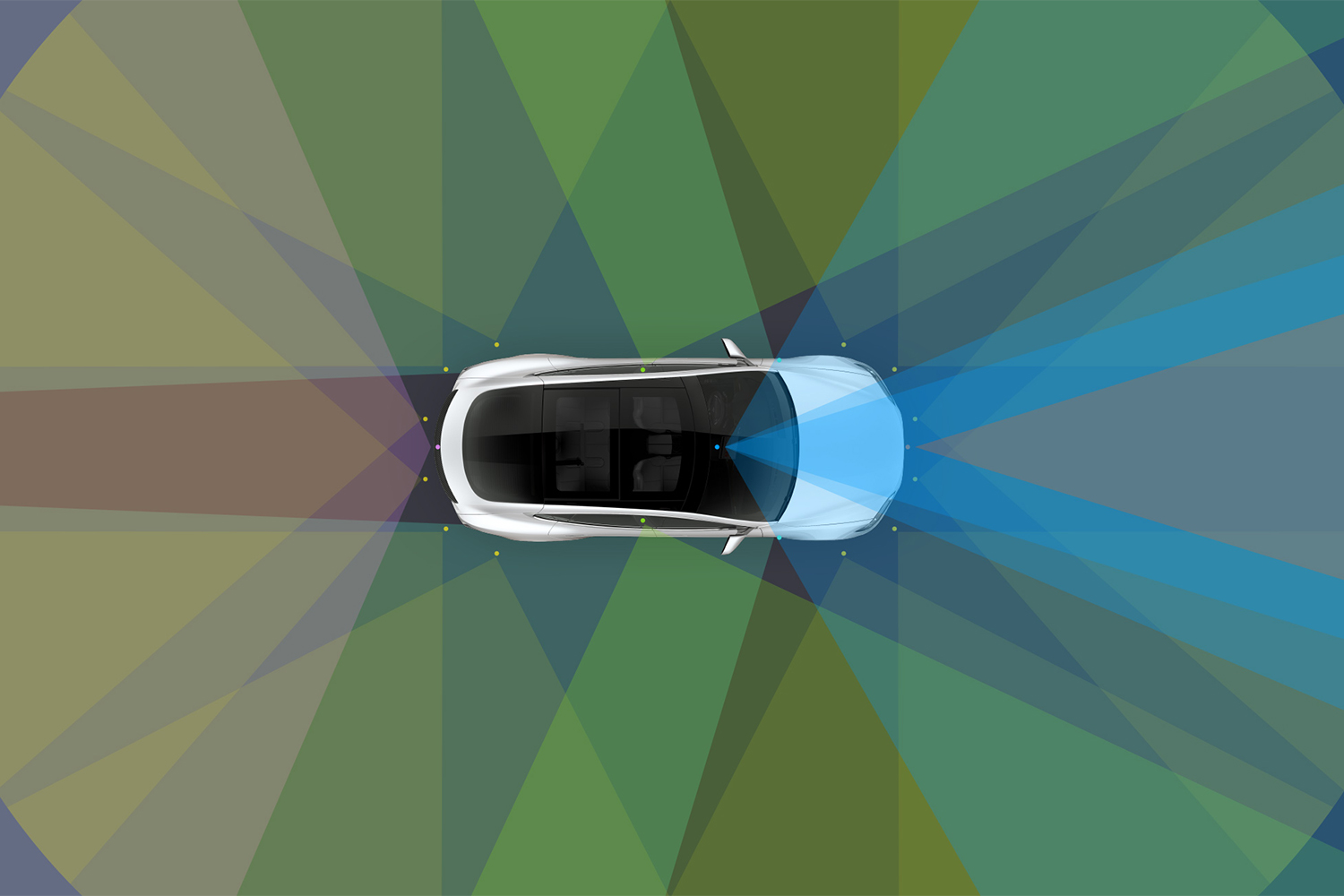

Once computer technology had caught up and the costs associated with radar, sonar and stereoscopic camera systems had come down, the safety focus shifted almost entirely to developing systems that could divert drivers from harm’s way as quickly and effectively as possible. By the end of the 2000s, this technology was quickly proliferating across the economic spectrum, making the leap from luxury cars to base models in a relatively short span of time, with the promise of a potentially accident-free future.

Computers Tag In, Humans Tag Out

It didn’t quite turn out that way. In fact, while the safety benefits of anti-lock brakes are well documented (along with the reduction in harm brought about by electronic stability control systems), the opposite has been true of the advanced driver’s-aid era.

After decades of falling numbers, traffic deaths began to climb in 2015, right around the time that advanced safety systems became ubiquitous. Although in-car fatalities started to settle in 2018, a troubling new trend cropped up as pedestrians and cyclists, unprotected by a sophisticated cage of steel and titanium, began to see their own surge in numbers killed out on the road.

In 2019, the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety released a study that found those who owned vehicles featuring systems such as lane-keeping assistance (which automatically steers a vehicle to stay between the lines on the road) and adaptive cruise control (which matches speeds with traffic ahead) were more likely to be distracted while driving. This was not a case of owners being unfamiliar with the technologies, either, as those who encountered these safety features the most often were significantly less likely to pay attention to the road than those who were introduced to them for the first time.

Time and time again, distracted driving has been shown to be perhaps the most dangerous menace on our streets. As a society, we are so engaged with our portable devices and confused by the increasingly complex infotainment systems stuffed into modern automobiles that we’re regularly taking our eyes off the asphalt long enough to put ourselves, and others, in life-threatening situations.

Autonomous Attitudes

Aren’t these computerized nannies designed to slap us on the wrist and instantly steer us out of harm’s way should the worst-case scenario suddenly appear dead ahead? In a word, no, and it’s here that the biggest disconnect between marketing muscle and semi-autonomous reality occurs.

Despite repeated messaging that each of these features represents one more rung on the climb to a self-driving future, in actuality the majority of advanced driver’s aids rely on an engaged occupant in the left seat to guarantee the strongest chance of survival. Intended to intervene when one’s best efforts have failed to react safely to a dangerous situation, they can offer useful assistance during the split-second changeover between recognition and action on the part of the pilot. What they aren’t designed to do is step in and steer to safety in every single instance.

The AAA study revealed that by creating a semi-autonomous driving environment, these safety systems were inadvertently encouraging drivers to pay less attention to the task at hand. A person strolling through the park with an umbrella under their arm is far less likely to check the sky for dark clouds compared to someone who’s forgotten theirs at home. In the same way, a driver who has become accustomed to a subtle chiming chorus alerting them to a vehicle pulling up alongside them, or the gentle tug of the steering wheel as it self-centers in the lane is less invested in remaining alert to the world on the other side of the windshield. Don’t forget all the false positives, the dings and gongs that we learn to ignore because from time to time even the most advanced sensors get things wrong, all fading into the background like chatter at a crowded party.

This delegation of attention frees up the mind for other pursuits, and a lot of the time that means reaching for a mobile phone and adding yet another layer of inattentiveness between driver and road. The car may not be truly on autopilot, but the brain definitely is, which pulls focus from the task at hand and leaves drivers completely unprepared for emergency situations that existing safety systems simply can’t handle, or circumstances in which this same safety tech (which is far from foolproof) fails to work as designed.

Don’t Be a Passenger

The paradox of active automotive safety systems is twofold. By fostering an environment where we feel safer than we actually are, they’ve allowed us to deprioritize the act of driving itself and experience it with a dangerously passive attitude. As our willingness to pay attention gradually erodes, so too do the skills acquired over a lifetime of driving that we can deploy in an emergency. It’s a vicious cycle that has born fatal fruit, particularly for pedestrians and pedalers, when a collision occurs.

That being said, there’s no doubt that active safety systems are at the very least mitigating some types of non-fatal accidents.

“Advanced driver’s aids are definitely saving a lot of drivers’ bacon on a regular basis,” says automotive journalist Craig Fitzgerald, pointing to insurance data from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety that indicates lower rates of collision claims for vehicles so-equipped. There’s also more than a little anecdotal evidence that older drivers are more comfortable forfeiting some of their responsibilities to technology, knowing that the hand-holding of a digital safety system could make up for the occasional lapse in skill.

As for the rest of us? Half-step automation of the driving process is inexorably eroding our judgment on the road and transforming us into fully-autonomous zombies sleep-walking at 60 miles per hour. In the liminal space between self-driving cars and those that are only part of the way there, it’s ultimately we who are responsible for resisting the temptation to turn off our brains and put our safety — and that of everyone around us — in the hands of a future that still hasn’t made it over the horizon.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.