Silvio Angori might well be impressed by the offerings at the recent Shanghai Motor Show. After all, some of the most storied names in car-marking were present: BMW and Lotus, Toyota, Mercedes and Volkswagen. But what impressed Angori most came from brands you’ve likely never heard of — the likes of BYD, Nio and Xpeng. And his opinion counts, because he’s the CEO of Pininfarini, arguably the world’s most influential auto styling company, responsible for the good looks of many a Ferrari, Alfa Romeo and Maserati.

“It blew my mind. I just stood there and said to my colleagues that the Chinese cars I was seeing were two generations ahead of anything on the market,” says Angori. “It’s not that car-makers in the west don’t have access to the same technology; it’s that the Chinese are brave enough to put it in their cars, and successfully.”

But then Pininfarina saw this coming. It opened a design office in China 13 years ago — well ahead of the trend — and has worked with other Chinese car makers you’ve likely never heard of, including Chery, one of the biggest, for decades. Why? Simply because, being a new industry, Chinese state-owned car makers — of which there are dozens — need help in styling its products to suit a western audience. But also because, unburdened by heritage, they’re open to Pininfarina’s more progressive ideas, and the use of progressive materials, like aluminum or magnesium alloy, or composite plastics.

“People haven’t yet grasped just how massive the Chinese car industry is, or what it’s doing, because we haven’t seen many Chinese car brands in the west yet,” says Angori. “But they’re coming, very soon and the impact will be dramatic.”

Just how massive an industry do the likes of, among yet more Chinese makers, BAIC or Jiangling, Great Wall or JAC, GAC and the giant SAIC — at one point China’s biggest company by revenue — actually represent? Last year Chinese carmakers produced 27.02 million units and sold around 26.86 million of them, according to the Chinese Association of Automobile Manufacturers. That represents roughly a third of all global sales.

That’s remarkable for a culture that, prior to 1980 — by which time U.S. and European car markets were well-established for at least half a century — didn’t even allow private citizens to buy a car for personal use. Back then it had no passenger car production at all. Now the independent maker Geely — ever heard of them? — owns Volvo, which you likely have heard of. China expects the number of registered vehicles in the country to top 200 million by the end of the decade.

That’s a massive domestic market. Right now only around 140 per 1000 people in China own a car, in part because there are high registration fees and a lottery for new car plates. But a huge population that’s rapidly expanding, and an already massive middle-class — roughly the same size as the population of Europe — looks set to put that figure on a steeply upward trajectory. That’s not only a cash cow for the Chinese government, but has meant that China’s car makers haven’t had to look to exports to thrive.

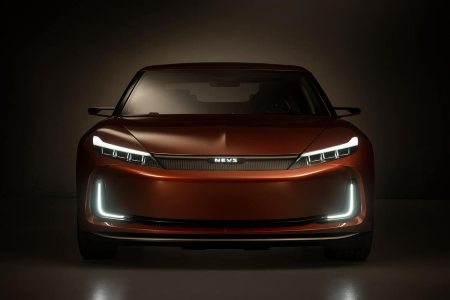

Apparently the Company That Bought Saab Built a 620-Mile EV in Secret

The NEVS Emily GT feels too good to be true, and it may stay a mysterySo hungry is local demand that many Chinese makers turn out several new model every three years, against the more commonplace international standard of every five years. No wonder western car manufacturers — Ford, Volkswagen and Renault-Nissan — are getting a toe-hold in China, too. This has especially been the case since the requirement for 50/50 joint ventures — 50% being the maximum share of a Chinese car-making operation that the Chinese government allowed foreign companies to hold — was dropped last year.

But that’s going to be a two-way road, and one with a rude awakening for the destination. Chinese-made cars are, of course, already on Main Street — Volvo XC60s, for example, are built for the U.S. market in China; General Motors builds its Buick Envision in China as well. Now Chinese-made Chinese brands are set to follow, and not least because the Chinese have spotted the opportunity to become a world leader in hybrid and electric vehicles, especially given the nation’s expertise in batteries and its access to the raw materials needed to make them. China’s EV sales almost doubled last year, with some eight million EVs expected to be sold by the end of this year. That would make up half of the world’s EV sales, with many home-grown models affordable in ways they still are not in the west. Indeed, if authoritarianism has its advantages, the government there has said it won’t allow the foundation of any car company that plans to make cars with conventional combustion engines.

“I think western car-makers understand the coming impact of the Chinese automotive market now. The problem is that they’re reacted very slowly to it, and especially its more recent emphasis on electric vehicles,” says Ran Zhou, China analyst with Vienna-based EFS Consulting, which specializes in the automotive sector. This prescient shift to EVs was, he says, actually driven by the Chinese government at least in part wanting to avoid the prohibitive patent fees involved in developing combustion engines.

“It was a way of getting away from Western tech and pushing their own, very latest tech,” he adds. “And now western manufacturers should be worried because the Chinese industry isn’t just start-ups anymore but big players filing their own patents [on EV and other tech].”

What’s more, Chinese car manufacturers are looking to dominate the EV market both through some unconventional products — creating new categories along the way, like the multi-purpose vehicle or SUV/sedan crossovers — and unconventional business practices, too.

Take, for instance, the first EV SUV from Lynk&Co, the European-designed, Chinese-made sub-brand created by Geely — which already sells in South America — specifically for export. Expected to enter the U.S. market next year, the model comes with a lifetime warranty and is available on a monthly subscription basis, which, Air BnB-style, allows subscribers to sublet use of their car for whatever fee they can get. It’s pitched at what the company estimates to be the 15% or so of motorists who aren’t that interested in cars, who aren’t wowed by the industry’s naval-gazing obsession with handling and horsepower.

Sounds Like We’re Getting a New Large Vehicle From Alfa Romeo

Other than that, details are minimalThe car also plans to offer free in-car connectivity. (Chinese makers are opening offices in Silicon Valley precisely to get ahead on this and other software.) Considering Gen Z’s disinterest in cars or car ownership, but also their internet-dependency, and the fact that Chinese demographics are relatively skewed toward the youth right now, you can see how this Chinese thinking aims to address the forces shaping the car industry of tomorrow, not today.

“Many of the most fresh ideas we look at here in Italy come from our Chinese designers in Beijing,” says Pininfarina’s Angori. “It’s just the way they look at the future of cars and how they will be used.”

Angori observes that the Chinese designers’ mindset is “one of experimentation, of providing what’s wanted by the newest generation of young consumers.” And while cars are not smartphones on wheels just yet, he adds, those consumers are less impressed by the car industry’s legacy brands. “They don’t want to know about performance, as it was in the era of the combustion engine,” Angori says. “They want to know what features a car can provide for them. For them it’s about how you can interact with the vehicle.”

“Against this progressive mindset western car makers can look rather boring in comparison,” adds Zhou. “Chinese car manufacturers are very aware of just how competitive the global market is and are really trying to be new and do something different. If there’s a new technology there’s an attempt being made to get it into a car — not least because that’s what Chinese consumers have come to expect.”

Industry analysts suggest it’s precisely this forward-looking attitude that will encourage western drivers to get over any hesitancy at buying Chinese-made and branded cars, even as they’re already well over any hesitation about buying Chinese-made clothes, cellphones and other electronics. Word-of-mouth will eventually speak to their quality.

“I think a lot of people in the west aren’t aware that brands they buy into already are Chinese because an effort has been made to hide the fact, but now there’s another more aggressive strategy coming through, underscoring that these cars are Chinese,” argues Zhou. That’s worked in other sectors, such as in telecoms, Zhou says, adding: “There’s a sense that once westerners have interacted with Chinese cars any suspicions as to their quality won’t last, excepting perhaps in those countries with long histories of car-making themselves.”

Quality is improving at a breakneck pace, too. That’s just as important to Chinese consumers who also, historically, have a somewhat jaded view of the design and manufacturing standards of its domestic products. In 2010, an 80-point quality gap existed between Chinese and international car brands, according to studies by the research company McKinsey. By 2016, that was down to a 14-point gap, one that has continued to close over the last six years. Both Japan and South Korea had to overcome the same doubts about their cars’ quality, and have done so successfully, to put it mildly.

“And I think the same will happen with Chinese cars,” says Angori. “Once awareness grows people will quickly abandon any pre-judgment. I give it around three years for that to happen.”

In contrast German manufacturers, responsible for 80% of the world’s premium cars, have been rocked by the Volkswagen Group’s emissions scandals. But that’s not to say the coming Chinese auto wave is without its hurdles. From the consumer’s perspective, Angori suggests there are concerns about the re-sale value of Chinese brand cars and possibly getting a hold of parts for servicing. Style, he continues, may be a factor, as well. “There’s a concern among Chinese manufacturers that their culture of style won’t be right for western markets,” Angori says. That, he adds, is something they haven’t had to worry about so far, considering the size of their domestic business.

At the industry level, Ran Zhou adds that Chinese car manufacturers have typically chased volumes at the expense of high costs — something they’re not used to managing — which has left them exposed. Other analysts have pointed out that the Chinese government has encouraged the creation of so many domestic car-makers that its industry is fragmented, making it hard for the better ones to build market share, invest in design and production and start exporting. With the Chinese consumer able to pick from more passenger car brands than any other in the world — upward of 130 of them, and with most of these Chinese — some consolidation is likely.

Telling these brands’ products apart isn’t always easy either. Building brands at all — which is different to manufacturing things, but, arguably, will be necessary to capture label-conscious western markets — is also something the Chinese government has been reluctant to do with its state-owned manufacturers when it’s happily making piles of money from operations as they are.

And then, this being China, there is inevitably geo-politics to work into the equation. The Economist, for one, has noted that there are concerns voiced in the U.S. over the fact that the software in these hi-tech Chinese cars might hoover up sensitive data. However, the publications argues that such a stance is likely a protectionist move, as the U.S. seeks to build its own EV industry as part of President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act.

Frankly, it’s going to take more than these concerns to stop the Chinese automotive influx. What’s more, this should be welcomed. Ran Zhou isn’t alone in suggesting that western car manufacturers have grown complacent, and in their reluctance to give up combustion engines, put themselves behind the curve.

This Chinese revolution may provide fresh impetus to get into gear.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.