Iconic architect Franklyn Lloyd Wright built up quite a following in the 150 years since his birth.

Tributes to the arrival of the son of a school teacher and a preacher-musician in Richland Center, Wisconsin on June 8, 1867 include MoMA’s “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive,” which opens on June 12. (The exhibit will feature roughly 450 works made from the 1890s through the 1950s, including some never before displayed publicly.)

In honor of this epic anniversary, exhibition curator Barry Bergdoll and Frank Lloyd Wright “master storyteller” Timothy Totten discuss how Wright claimed his unique place in architectural and world history, surviving a scandal and tragedy that would have crushed a lesser man.

The very fact Wright has a devotee regularly giving three-hour presentations on his life for the general public suggests his unique legacy among architects: After all, no one performs “A Night with Renzo Piano.”

Here are some of the reasons for his well-deserved reputation:

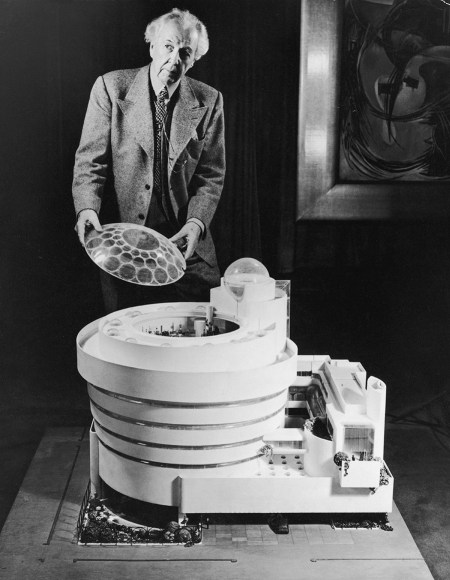

Wright’s life was as long as the shadow cast by the Price Tower. He died at 91 in 1959, missing the opening of his Guggenheim Museum in New York by just six months. (Great architects often have a strange genius for survival: Frank Gehry is 88 and I.M. Pei recently turned 100.)

Wright’s career spanned one of history’s most eventful stretches. Totten notes that Wright was born “two years after the Civil War” and died while “Kennedy was running for President.” Wright lived through two World Wars and Korea for good measure, during a time when cars and plane travel went from unimaginable to routine. For that matter, Arizona—where Wright built his winter home/school Taliesin West and ultimately died—didn’t become a state until the architect was already 44. During this transformative historical period, Wright spent roughly 70 years relentlessly working and advocating. As the MoMA notes, Wright was “a radical designer and intellectual who embraced new technologies and materials, pioneered do-it-yourself construction systems as well as avant-garde experimentation, and advanced original theories with regards to nature, urban planning, and social politics.” Bergdoll asserts that “modernism in this country cannot be understood without engaging with his work.”

Wright’s personal life once overshadowed his designs. Wright is unique among the great architects for achieving much of his initial name recognition less through his creations than, as Bergdoll puts it, “personal scandal.” And what a scandal it was, as in 1909 America learned about Wright “running off to Europe with a client’s wife and abandoning his own wife and children.” (This period was deeply explored in Nancy Horan’s 2007 bestseller Loving Frank.)

Then things went from scandalous to nightmarish. Taliesin, Wright’s Wisconsin home/school, was the site of carnage as unspeakable as it was baffling. In 1914, the servant Julian Carlton killed Wright’s lover Mamah Bortwick Cheney, her two children, and four other people as well as burning the property and swallowing acid. (He survived for almost two months, but never revealed his motive—the massacre seems to have been triggered by an insult by another employee.) The New York Daily News later wrote about the incident with the headline, “Wright-mare!” Totten sums it up: “[Wright] was a walking soap opera.”

Wright did both the epic and the intimate. Today, Wright is most remembered for his work. Generally famous architects are associated with massive structures: think Gehry and the Guggenheim Bilbao. Wright, of course, has his own Guggenheim. You can see it in the video below, in which artist Matthew Barney demonstrates just how remarkable Wright’s creation is by, among other things, climbing its interior. (Totten observes that architecture is about “being in the space” and how architects “shape the space to invoke a feeling.” Consequently, this article favors videos over photos—it’s not the same as a personal visit, but it gives a better sense of Wright’s vision than a still image.)

Even so, homes are essential to the Wright legacy. Totten says that makes sense, because a number of people generally need to approve of a larger construction project: “Does a committee really want to hire a guy who’s had seven people murdered at his house and he got destroyed in the press because he was living with another’s man’s wife?” Wright tended to be ideally suited for dealing directly with an individual or couple. The result was his creation of remarkable residences including Fallingwater outside of Pittsburgh, which Totten dubs the “‘Mona Lisa’ of American architecture.”

There are literally hundreds of other Wright homes worth seeing—Totten has personally visited over 200 and counting of them. He particularly recommends journeying to Tallahassee, Florida’s Spring House and Samara House (or SAMARA) in West Lafayette, Indiana.

Wright forged a compelling connection with the public (once they caught up with him). Truly, Wright was a man ahead of his time. Bergdoll notes that while initially Wright’s clients “were considered radicals for working with such an unconventional architect,” when people think about those same homes today, they “see them as cozy and homelike.” Likewise, a public life that once scandalized a nation is now a “charming piece of past American history.”

Wright’s best might be still to come. Extraordinary as his finished buildings are, Wright left behind designs for arguably even more remarkable structures. In 1956, he proposed a mile-high skyscraper, four times the height of the Empire State Building. (The world’s tallest current building, Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, only reaches about half this altitude.)

There are other Wright-designed buildings that still need to be built. Bergdoll says “the design for a Rosenwald School for African American children which would have made a fine school for rural areas everywhere in America had it been put into practice.” Totten chooses the San Marcos in the Desert project as his dream structure: “Meant to be built from the textile block construction method he had devised for four earlier California homes, the hotel resort would have featured three terraced floors of guest rooms accented in copper and glass, with an emphasis on the rugged natural beauty of the desert just outside the window.”

How to properly celebrate Wright’s 150th. The best way is to visit his work: actually hear the falling water at Fallingwater. If you want as much Wright bang for the buck as possible, head to Chicago and go straight to his Home and Studio in Oak Park. (As a bonus, the surrounding area contains a total of 21 Wright-designed structures.) And while you’re in the Midwest, stop off in Racine, Wisconsin. It’s home to the Johnson Wax Building, which both men adore. (Bergdoll calls it simply “one of the great spaces ever created in the history of architecture.”) Get excited to tour it in person with the video below. Happy Birthday, Frank.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.