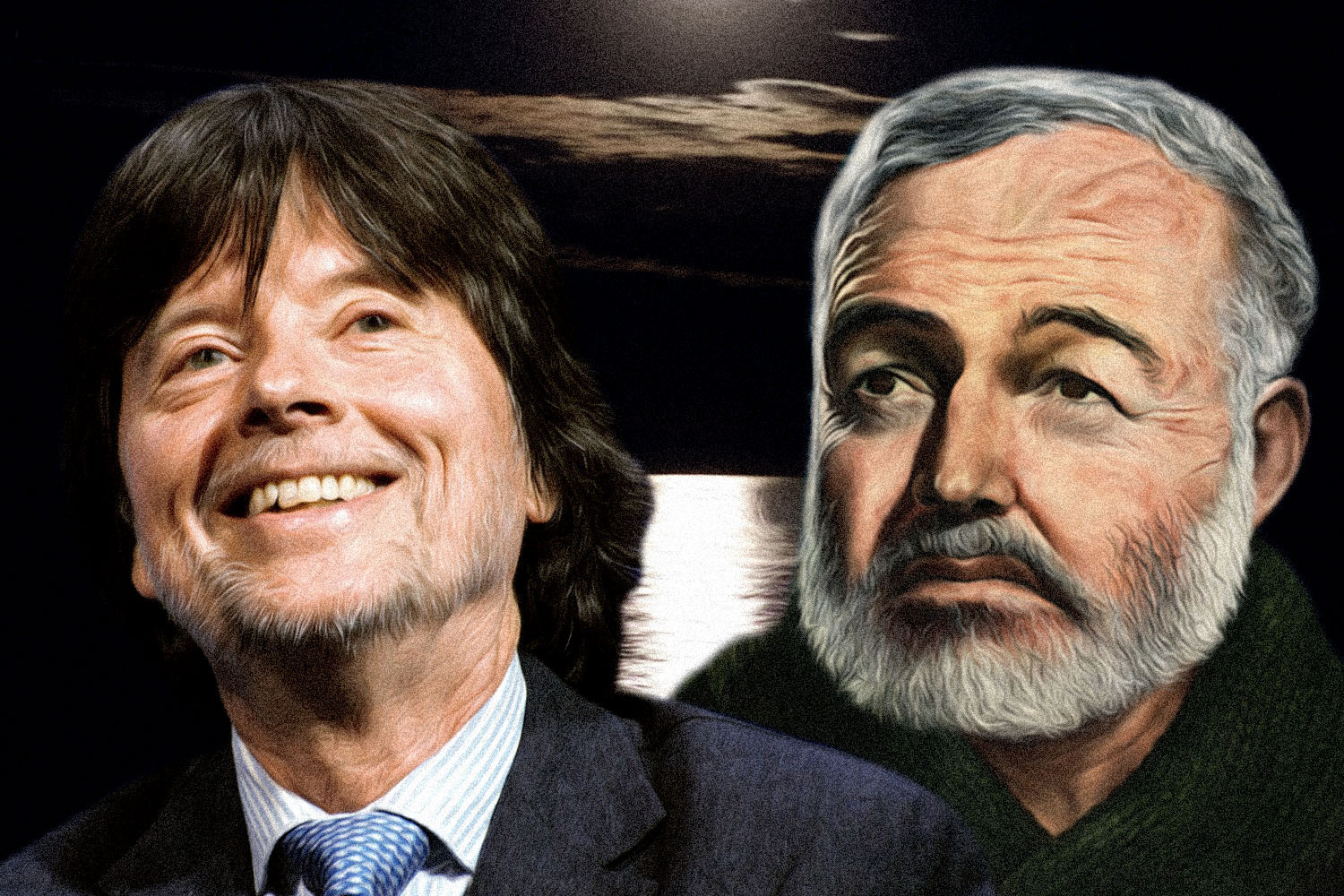

Brian Skerry is a photojournalist specializing in marine wildlife and underwater environments. For over two decades he has been a photographer for National Geographic, logging more than 10,000 hours under the surface of the sea.

Recently, Skerry traveled to New Zealand to photograph orca, or “killer whales,” as part of his National Geographic special Secrets of the Whales. There he witnessed new hunting behaviors and came face-to-face with the apex predator. His story appears as told to Charles Thorp, and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Orcas are animals that stir my soul and my imagination, as they do for many. They are arguably the most intelligent animals in the ocean, and I mean scary smart. I have had the pleasure to work with them a few times on various projects for National Geographic.

Back in 1994, I was one of the first Americans to go to the fjords of Norway to photograph their carousel feeding method, a cunning technique where they collectively herd dense groups of herring into tight bait balls, and then they stun the fish by slapping their tails by the surface of the water. Once a bunch of fish are floating stunned, they take turns eating while the others continue to chase.

I have a vivid memory from that trip, where I had jumped back into the water with a group of orca after getting a pony bottle, an oxygen container that helps you say down in the water longer. I had been free diving before and the addition of that cylinder changed their reaction to me. Suddenly they were paying attention, and because I was in the vicinity of their food they may have been concerned I was a competitor. I will never forget that feeling of them looking at me, like I was being scanned by predator supercomputers.

For my new special Secrets of the Whales, I wanted to go to New Zealand to observe the shallow water hunting that they do around the country’s North Island, chasing stingrays in a few meters of water. The pressure was on because I only had about 10 days on the ground there, which is next to nothing when you are doing a complicated shoot like this.

On the logistics side, I have managed my own for decades while working for National Geographic. Going anywhere internationally can be difficult, especially when you need visas and carnets, but also add the fact that we are traveling with 20 or 30 cases of gear. Sometimes I will only have two days back at home in Maine between monthlong trips.

Once we arrived in New Zealand, my crew connected with Dr. Ingrid Visser, a marine biologist who has spent her life studying orca, and a local underwater videographer Kina Scollay. We ended up setting up in the Tutukaka area. The place is famous for its proximity to the Poor Knights Islands, one of the marine reserves that has really come back as a very resilient ecosystem.

It is a magical place with hills, windy roads, and set against the magnificent coast. The region is pretty remote. Ingrid has a home overlooking the water in that area, and on occasion you could see orcas out in the ocean. The crew stayed together at a motel. As soon as we got there, Ingrid sent out a message to her network in the area telling people that we were there for National Geographic and were looking for orcas.

Days went by and nothing happened; we would be playing ping-pong at the motel. That was until I was woken up at five in the morning by one of my crew saying that we were a go. Luckily, the trucks were always packed, so we were able to take off immediately. The drive was sometimes three hours through the backcountry, along narrow passes, to get to the landing.

Ingrid would usually be waiting for us with her inflatable fib already in the water, anxious to get us out there. So we would finish what’s left of our coffees and jump in. On the boat we would get our wetsuits sorted and prepare our pony bottles. Once we got to a distance where we could see the orcas we would start to slow down, Ingrid would try to give them adequate space so that we weren’t disturbing them too much.

There is a natural understanding that orcas are animals with the potential to do your great harm. We have witnessed how intelligent they are in their hunting behaviors. We have seen their techniques, washing seals off of ice floes to kill them. Or when they jump up on the shores of the Falkland Islands to grab elephant seals.

These orcas were hunting in shallow mangroves and harbors for stingrays. I never dreamed I would get to see it live. There are a lot of things that have to go right to get a good image of any whale, because in marine photography you need to get close. I mean within a few meters of their space, and that is completely on their terms, not yours. You aren’t going to sneak up on a whale, it is their environment and they know exactly what is going on.

But we ended up being incredibly fortunate. Not only did I witness their behavior, but this huge female orca came out of the fog towards me with a stingray hanging out of her mouth. My mind was in overload, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Then she dropped it right in front of me, like she was offering it to me to eat.

I followed the ray down as it drifted, because I had been told that if that ever happened, to stay with the food. She swam around me a few times, and I could see her out of the corners of my eyes circling. Eventually she appeared again, almost like a movie, right in front of me as if to ask me, “Are you going to eat that?”

Once enough time passed, she gently floated down and picked the ray off the ground and started sharing it with another from her herd. I was lucky that Kina was right there with me so he was able to capture the whole thing on video. I am not sure I would have believed it myself if we didn’t have the footage.

This series is done in partnership with the Great Adventures podcast hosted by Charles Thorp. Check out new and past episodes on Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts from. Past guests include Bear Grylls, Andrew Zimmern, Chris Burkard, NASA astronauts, Navy SEALs and many others.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.